01 Oct Books: Writing the West (Fall 2014)

If Not for This

In his new novel, If Not for This (Red Hen Press, $14.95), Pete Fromm weaves a powerful love story within the misshapen lives of Maddy and Dalton, a couple who meets during that peculiar time of life when poverty is beautiful and easy, a shack that is collapsing around the rickety ladder-reached bedroom loft is a palace, and dreams of a business that will flourish around a passion for rivers are just within reach.

When Maddy and Dalton meet, Maddy has a comfortable arrangement with Troy, her older boyfriend with whom she lives during the summers of her college years while she’s working on her skills as a Wyoming river guide. It’s comfortable, but not inspiring. Dalton is a young, handsome boatman working for a rival outfitter, and when they meet at a party, Maddy immediately assumes that Dalton will be more interested in her beautiful friend Allie than he is in her. But soon Maddy has stepped away from the faithful Troy and Maddy and Dalton’s love affair is roaring along just like the river, a metaphor that Fromm employs, but doesn’t overuse throughout the book.

The reader knows from the beginning that the idyll Maddy and Dalton have created is going to be darkened by storm clouds. They have a beautiful wedding; the guiding business they found is flourishing and going international; and they’re ready to start a family (they name their first child Attila because of their business connections in Mongolia, though they call him Atty, horrifying, but ultimately something that happens when people name children). The course changes when it appears Maddy has mono. Her symptoms don’t improve, leading them to the simultaneous discovery that she’s pregnant and is diagnosed with multiple sclerosis.

Fromm isn’t the first Montana author to tackle MS and its repercussions in fictional form. Mildred Walker’s great 1938 novel Doctor Norton’s Wife was considered to be such an accurate portrayal of the disease and its effect on patients and their families that it was used in medical schools to help doctors understand their patients’ experiences. It’s tender and thoughtful and firmly rooted in a pre-war world. Fromm’s depiction is grittier and more visceral, and just as much of its time as Walker’s. Maddy’s wit and her edge are revealed in a scene that would have been unimaginable in a heels-and-pearls era of motherhood, when a neighbor stops in to introduce herself:

“I get back after my onions, trying to chop with my left hand, my jittery right ready to dodge. When Atty says, ‘Mommy,’ I turn to find a woman standing in my kitchen, some adult who would follow a toddler’s invitation into a strange house, and I dip my hand behind my back and stammer out, ‘Um, hello?’ without a thought beyond wondering when I last washed my last hair. It’s not the most gracious welcome ever delivered, but it beats ‘What the f—?’ which feels more appropriate.”

Fromm immediately pulls you into the era and the outfitting lifestyle of the late 20th century because his language and his characters and his scenarios are so believable, starting with Maddy, who we know from the prologue is about to narrate her own sad and triumphant story. Maddy is so believable because she starts out as such a recognizable “type” in contemporary fiction — the girl who doesn’t think she’s as attractive as her friend, who can’t believe her luck when the handsome and seemingly unattainable boy is interested in her, the insecurities pour out all over the page. But as she narrates her own story and reveals her internal struggles, her smart-ass and powerful perspectives on her life and family, she shows her strength. Ultimately her character allows the river to reflect the headlong rush of life and circumstances becoming utterly critical to how the story unfolds, and the heartbreak that is all too realistic. In fact, the metaphor is part of the appeal of this book, because it doesn’t become precious or forced.

Where the brilliance of this novel shines through is in the depiction of the love and struggle that exists between Dalton and Maddy and eventually their two children as we see it through Maddy’s baffled and infuriated and grateful-but-not-happy-about-it eyes. When she demands to know whether Dalton has ever considered leaving her, she understandably becomes infuriated at the saintlike Dalton, as well as at her disease. But in the end, we can see how she experiences a world that is patently unfair, yet still a world where she can call herself one of the “Luckies.” When Dalton at last reveals his own perspectives in the last chapter, have a tissue handy.

Let Him Go

Let Him Go by Larry Watson (Milkweed Editions, $16), winner of the 2013 Montana Book Award, is being released in paperback this fall, and its stark and subtle depiction of rural mid-century Montana makes it a worthy successor to Watson’s much beloved Montana 1948. Margaret and George Blackledge have left their home in North Dakota in search of their young grandson, years after the death of their son in a horseback accident and the departure of his young wife, who has cut off contact and remarried. Margaret Blackledge is clearly a woman to be reckoned with. She packs the car with camping supplies and intends to head west with or without her husband George to find Jimmy, the grandson, and bring him home with or without his mother. George, who is a former sheriff, becomes her reluctant accomplice.

At times humorous and sweet, dark and suspenseful, the little moments in this novel make it special. The day after they find Jimmy, the Blackledges explore the little Montana town of Gladstone, the nearest town to the tiny settlement of Bentrock where their grandson has been living with the dangerous Weboy clan. The couple is obviously full of uncertainty about what the future holds for them and for their daughter-in-law and grandson, and yet seem completely confident that their righteousness will carry the day. Gladstone is clearly no metropolis, though neither is their home of Dalton, N.D. Still, they wander through its streets as they wait for their daughter-in-law to determine their fate:

“They spend the afternoon in and out of their car, wandering around Gladstone, and since the town is not their home everything they see and hear they compare to home. As they drive down Main Avenue they notice that the saloons have more business than any in Dalton would have on a weekday. In Dalton those three young women would never stand outside the drugstore openly smoking cigarettes. George and Margaret go into the Red Owl just to check prices and find not only that bread, milk, eggs, coffee, and hamburger are sold for less but also that the shelves are stocked with brands and products unknown in their grocery. And in the dairy section, margarine is available as well as butter.”

It is easy to consider the Blackledges as two somewhat doddering and elderly people, set in their ways, and acting out of the grief for their lost son. But they surprise at nearly every twist and turn of the plot. The events that Margaret sets in motion by loading the car and searching for Jimmy come rushing toward them and take the reader into a harrowing encounter between the Blackledges and the Weboys. But just as Margaret accepts the responsibility for what she has done, it is George who takes up the cause of restoring their grandson to them with even more fervor than his wife. As it turns out, it is not their choices or even those of their grandson’s mother that shape the events that play out in sinister and horrifying fashion, but we’re left wondering how different Gladstone truly is from Dalton and what the future holds for the family left behind.

The Ploughmen

The story at the heart of The Ploughmen (Henry Holt, $26), can be summarized fairly succinctly: A young lawman befriends an elderly killer who has finally been incarcerated after decades of evading capture. It’s an intriguing enough premise, but to describe Montana writer Kim Zupan’s debut novel in such simple terms is totally inadequate, and yet effusive praise — well deserved or not — seems inappropriate in its own way. Tucked beneath the mystery at the heart of this novel is a relationship that isn’t truly acknowledged or defined by either man but that comes from a kinship that relates back to the beautifully evoked landscape of Montana and the childhood traumas they both experienced, begging the question why does one man take one path and not another.

Val Millimaki, the young lawman, has been assigned night duty at the Copper County sheriff’s office where he works, straining his already fragile marriage to the brink. It’s clear from the start that he and his wife were ill-suited, but still your heart breaks for him as his sleeplessness and despair grow, especially when she moves out of their remote Montana cabin and into a girlfriend’s apartment in town. By contrast, the mystery of what happened to prisoner John Gload’s wife hangs between the two men tinged with Gload’s mostly tender memories of her. The friendship that grows between the men doesn’t necessarily seem all that unlikely, nor does it exactly seem like a friendship. Millimaki is under orders to spend time with Gload because the sheriff wants information from Gload about his many decades’ worth of crimes. Gload’s motives for actually talking to Millimaki are unclear, especially as he strings along another one of the deputies.

This beauty of this novel is subtle, and Zupan masterfully weaves together different times and perspectives around the central premise in a way that never seems contrived or overworked. Lovely descriptions and precise word choices paint images of the sheriff, the county jail, the lonely cabin that Val and his wife live in (to say that they share it or share anything would be inaccurate, and the descriptions of her unraveling while she’s alone there are vivid to the point of being unnerving). The even lonelier home of John Gload and his wife and the bleary-eyed weariness and grief that Millimaki faces are reflected in the words of the witnesses to their despair.

After his wife leaves him, Millimaki stands in the sheriff’s office reflecting on what’s happened to lead up to that choice:

“The younger man had turned his gaze to the streaked single window with its latticework of bars and seemed altogether lost there. The sheriff was unsure if he’d even heard. In any case, he was embarrassed to have spoken aloud the philosophy he’d formulated through years of such counseling, years of his own uncounselable grief. He notes in the cruel light the deep furrow that had appeared between Millimaki’s brows since he had last seen him and that his pale eyes within their dark grottos were set in a perpetual squint, as if in seeking sense in his world, or succor, he had taken to examining life at the level of mites or atoms.”

These small glimpses into the hearts of the men in The Ploughmen together make up a simple story that uncovers the complexities of the human heart. And yet it’s also about the West, the big land that is covered by the open acres where ranching and farming and mining and hiding and running and disaster and loss overlap.

The Steady Running of the Hour

The Steady Running of the Hour by Justin Go (Simon and Schuster, $26) is the kind of first novel that makes a writer’s career. It’s ambitious, meticulous, features a cast of complex, striving and hapless characters each on a quest, some separated by decades and continents. Tristan Campbell is a young American and recent college graduate without a phone in his apartment or a plan for the future. He has been contacted by a British law firm because they believe he may be heir to a fortune left behind by English mountaineer Ashley Walsingham, who died in an attempt to summit Everest in 1924.

Campbell flies to London to begin a search to prove that he is that heir — though all the while protesting that the money isn’t important — a journey that takes him from London, across the channel to Paris, to Berlin and finally to Iceland. His protestations that his investigations aren’t about the money oddly ring true, since he’s discovered bigger family secrets are at the heart of the mystery. In order to prove that his great-grandmother was the woman Walsingham named in his will, he has to fly in the face of long-held family beliefs that this younger sister of the woman he’d presumed was his great-grandmother had died childless and unmarried. The scenes of Campbell’s improbable encounters and startling discoveries in his historical research reveal how little can be truly known about the past — and how easily it’s obfuscated by assumptions and family tradition. What is left behind in the letters and documents preserved in archives or stored in attics can offer bald facts without revealing the truth.

Alternating with scenes between the former lovers, Imogen Soames-Andersson and Ashley Walsingham, in the years of the Great War and their separation thereafter, ending with the tragedy that takes Walsingham’s life, the story of Campbell’s hopes reveals that what he’s looking for is an explanation of who he is, perhaps a much greater inheritance for someone not sure what he’s going to do next. But it’s not a simple construction of parallels between his life and that of his purported ancestors.

This is a romantic story, but it’s also heartbreaking and unpredictable. Soames-Andersson and Walsingham are star-crossed and hampered by circumstances, but are equally victims of their own choices and personalities. Neither is a character easily reduced to caricature. Campbell makes choices based on hunches and flights of fancy but seems much closer to the truth than the lawyers who are insisting on fact. This is the kind of book that stays with a reader even as you’re compelled to turn pages faster to find out what happens, coming to the end sooner than you’re willing to let go of the quest at its heart.

Of Note (Books, Music, Movies & More):

A Prairie Year: Messages to Max, by George Rohde (Sweetgrass Books, $19.95), is an informative and pretty photographic journal that conveys the late Rohde’s passion for the prairie through a lifetime career of photography and teaching. Based on photographic postcards that Rohde began sending his grandson, Max, when he was 4 years old, the collection is a fitting tribute and a lasting legacy. The month-by-month organization of the photographs captures the essence of a prairie year, from the images of white-tailed jackrabbits huddled and facing into the driving snow, to the birth of white-tailed deer fawns in the soft light of spring, to the changes of the seasons that take the prairies from their greenest state to the grays and browns of fall. This book reveals the beauty in small things and creates a mosaic of the vast openness of the prairie.

Jerome O. Brown’s debut novella, Calves in the Mud Room, is somehow sweet — a rough-around-the edges portrayal of the inner life and anxieties of a teenager caught between the past, represented by the ranch his grandfather willed to him, the present miserable homelife he’s enduring with his volatile and irresponsible mother and stepfather, and a hazy future that’s represented by the chance to go to the big school dance with one of the prettiest, richest girls in town. Brown captures the raw cold of February when any of winter’s appeal has been lost to the exigencies of dealing with livestock on the ranch and he evokes the smells and sounds of both the 1953 Ford pickup, also inherited from the grandfather, and the exquisite reek of hormones of the high school dance. This short work demonstrates Brown’s potential as a writer but stands alone for its portrait of a teenager’s inner life and anxieties under what seem to be extraordinary circumstances and its reflection on the power of family to sustain and destroy us.

Charley Waterman’s Tales of Fly-Fishing, Wingshooting, and the Great Outdoors (The Derrydale Press, $18.95) is a beautiful reissue of a collection of essays from the career of the late, great Charley Waterman on fishing, bird hunting and the great outdoors in general. First published in 1995, these stories came from Waterman’s extensive and delightfully wry and witty columns in Fishing World, Gray’s Sporting Journal, Florida Sportsman, Gun Dog, and Wing & Shot, among others. To say that Waterman was prolific, is not an understatement. Nor is it an understatement to say that as one of America’s great outdoor writers, he backed up his work with a love for and appreciation of the fishing and hunting life he revealed through his words. From the art of luring trout to take mayflies when fishing in a spring creek, to what shooting lessons can do to help or harm your aim, to watching his wife try to find a pair of waders that fit her in an era before women’s needs in outdoor wear were accommodated by manufacturers, his appeal is in the disarming way that he unveils his joy. A wonderful book to be rediscovered by a new generation of outdoor readers and studied by outdoor writers.

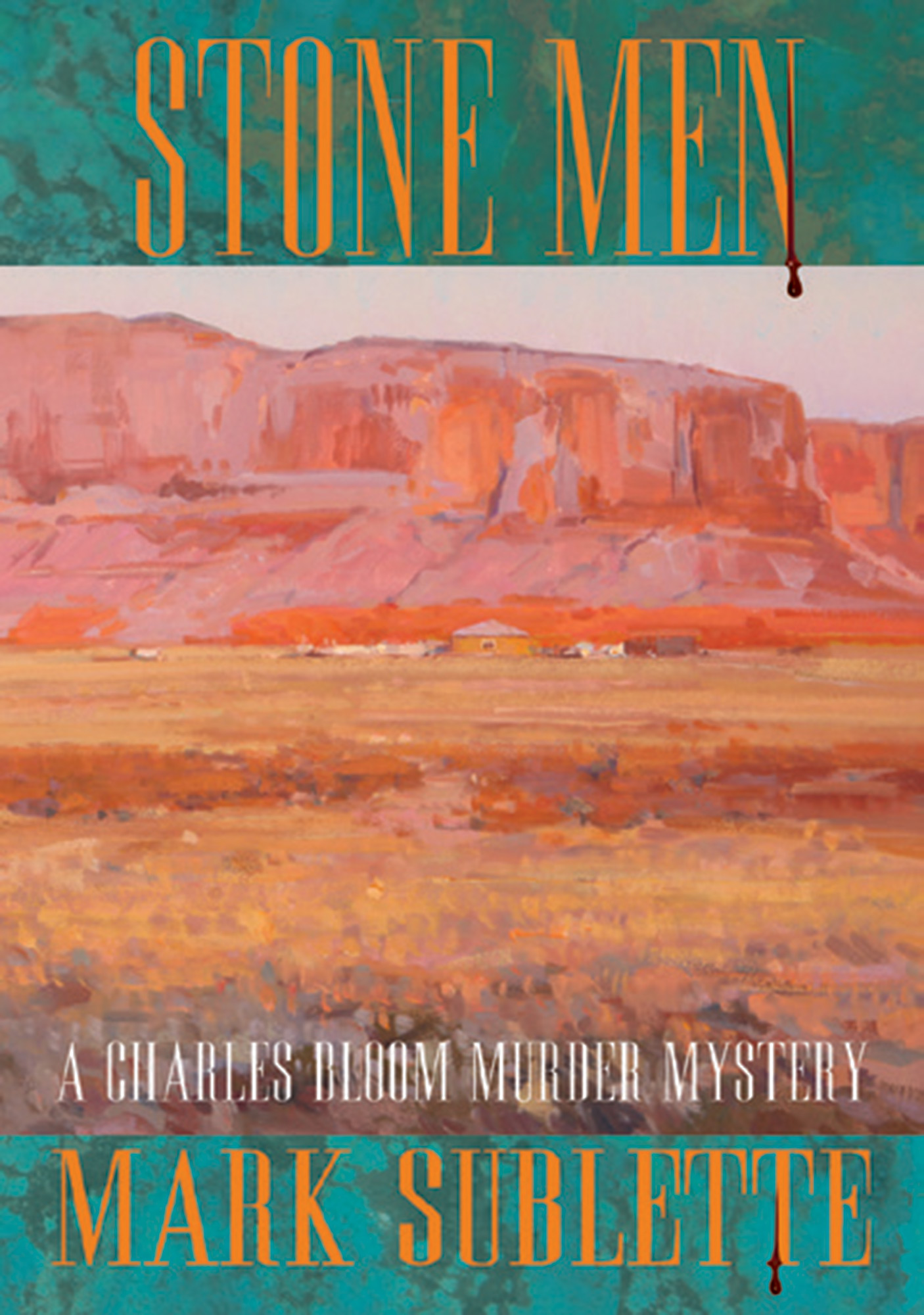

Stone Men, by Mark Sublette (Just Me Publishing, $24.95), is the fourth in the Charles Bloom Murder Mystery series, a tale that immerses the reader in the world of the “stone men” turquoise hunters and dealers in New Mexico, near the Navajo reservation. The story centers around gallery owner Charles Bloom, who agrees to help the FBI run a sting operation to uncover who is making and selling spurious turquoise jewelry and representing it as Navajo made, and a stone man known as the “President” who has just uncovered a vein of truly priceless turquoise. Bloom, whose wife, Rachel Yellowhorse, is a Navajo artist, has developed a reputation for his detective skills and seems to be the perfect man for the job of infiltrating the trade in fake jewelry. He can purchase the bracelets and other items with the assistance of his nephew and offer inside information to the agent running the investigation. It seems simple enough until it becomes clear from the attempts on the President’s life that this isn’t just about the jewelry. Following in the footsteps of other mystery fiction set in the Southwest, this book effectively evokes the landscape and the culture, and Sublette keeps readers in suspense as the thrilling reasons behind the suspicious interest in this turquoise are revealed.

The new novel by Dr. Frank C. Seitz, 1000 Daggers (Christopher Mathews Publishing, $14.95), seems both timely and prescient as it reveals the world of an imaginary staff and patients at a Montana Veteran’s hospital. Dr. Seitz weaves together a story of office politics, national politics and the heartbreaking business of recovering — or trying to recover — from what war means to the soldiers who come back and the people who try to love and support them. From the psychology interns, to the grizzled Vietnam vets, to the well-meaning but ineffectual doctors, to the villainous and diabolical Dr. Fredericks, the inmates of the hospital are all part of a system that’s completely broken — and completely reflected in the real-life struggles faced by the veterans and the hospitals that serve them every day. But there’s compassion in the way these characters relate to each other and to their situations, and a deep humor in their explorations of ageism, misogyny and the trauma they’ve all faced. The steps that the hero takes to right the world feel like a sweet redemption and are laugh-out-loud funny. The cover and the marketing copy for this book completely belie the witty and wry tone that Seitz brings to his subjects and his characters. This is not a depressing book about post-traumatic stress disorder and how it has affected so many returning veterans. Look past that and you’ll find a clever, charming fable about a group of entertaining, well-meaning and bright people that reveals a lot of truth about all of us.

No Comments