21 Aug Mentoring the Artist

ROBERT MOORE WORKS IN AN OLD BEAN WAREHOUSE in Declo, Idaho, and lives with his wife and six children on his land nearby. At first glance, he is the quintessential rural Westerner in his tattered Carhartts, boots and hat (maybe two if it’s cold). But, Moore does not spend his days with crops or cattle. He raises paintings, and painters.

In the highly anxious, competitive world of art, it is rather typical to be self-preserving, tightly guarding hard-earned proprietary secrets. But, that would run completely contrary to Moore’s character. He quietly aligns himself with the old western notion that helping a fellow homesteader or traveler is simply sowing good seeds in good soil. To that end, and with a startlingly humble generosity, he opens his warehouse painting studio, his skills, and his experience to a small cluster of painters — currently three — who work and study with him.

Moore is suitably educated, lauded, and collected as an artist, and has clearly carved his niche in the world of Western oil painters. For many artists, that would be enough. But the usual definitions of success just don’t fit Moore. Like many Westerners, he rides into the backcountry on an all-terrain vehicle, but his is not loaded with hunting gear. Rather, his is a self-contained pochade carrying oil paints, brushes and canvasses for working en plein air. His boldly colored landscapes defy the fact that Moore is completely colorblind, and are often created with brushes held in both hands simultaneously.

The vast American West offers solace and privacy to those among us who never quite fit any mold. The sheer size of the place allows us to stretch out our oddness and exercise our quirkiness without much oversight from convention. We tend to be accepting, even respecting, of our differences. Near a southern Idaho fork in the old Oregon Trail (often touted in the 1800s as the place where people who could read moved on through to Oregon, and people who couldn’t read headed for California) is this typical small town where much of life circles around farming or ranching.

“I just believe that these artists have a similar mindset and that they will also give freely of what they have been given,” Moore explains. “They will all produce different harvests, but I believe it will be passed on to others in a spirit of giving and love — it comes through in their canvasses.”

Missoula gallery owner Dudley Dana shows Moore’s work along with that of his apprentices, and notes the commonality amongst the artists. “They are very similar people, very calm, giving, and kind, with an extraordinary sense of gratitude about them,” says Dana. “You can see in their paintings that they have been strongly influenced by Robert, but their works are actually quite distinct.”

David Mensing

David Mensing met Robert Moore many years before they painted together. Raised in Iowa and educated in architecture, Mensing worked in his chosen field for about three years when he realized, “I’d rather go work at a camp.” He traveled west and hired on at Camp Perkins, a youth camp near Alturas Lake nestled in Idaho’s majestic Sawtooth Mountains. What seemed like an indeterminate break turned into a year-round stay for five years. It was there he met fellow camp counselor, Robert Moore.

“The start to our relationship had nothing to do with art, really. There were, and still are, a lot of similarities between us, some of our gifts and some of our thinking,” Mensing recounts. (It is interesting to note that both artists met their future wives at Camp Perkins.) “Robert still reminds me that if you are thinking about art, you have to dig into your own soul. You have to go way beyond technique.”

Mensing studied with Moore in workshop settings from 2000 to 2002, all the while discussing the idea of creating a life as a full-time fine art painter instead of a career architect. “Of course,” Mensing says, “I’d much rather be doing the art.”

Moore believes in Mensing completely and the men have become close friends while painting together. “David is very hardworking and passionate about his work. He comes from very high discipline which serves him well,” Moore reflects. “His temperament is very focused and that shows in his subject matter, the complexities of sky and landscape and masses in a simple tree or cloud form. His work is more than just representation, you can feel the lightness of the clouds, the depth of the sky and landscape. David is a very good designer.”

The more worldly perception of success parallels Moore’s words about Mensing’s work. Galleries and collectors alike seek him out. “How we experience creation around us can be brought out in a painting perhaps even more than in a photograph. My titles and my paintings reflect my spiritual state while I am working. The emotional element of the way paint is applied to the canvas, if I do it well, should go back to the experience. The application of paint, color, contrast, all of those things should represent more of the feeling of being there.”

Francis Switzer

Francis Switzer is a young painter who came into Moore’s life and circle before he was even born. Switzer’s father — renowned painter Scott Switzer — was a fellow student with Moore at The Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, Calif., in the late 1980s. The young Switzer painted occasionally with his father, selling his first painting at the age of 8 (1994) to a collector who wanted to “get one while they’re still affordable.”

Born in Billings, Mont., Switzer remembers that his family moved often during Francis’ childhood. Home-schooled for many of his school years, he enrolled in a public school in Alaska where his high school art teacher entered one of Switzer’s paintings in a national contest in 2002. The result was a Congressional Art Award and the opportunity to participate in an exhibition at the United States Capitol.

After high school, Switzer moved back to Montana with the singular goal of painting. He worked for three years as a stone mason, painting whenever he was not laying stone. In 2007, Moore encouraged him to move to Idaho and paint full-time.

A humble young man of extremely few words, Switzer puts it simply. “I want to paint full-time, for my lifetime. I hope to travel around the world painting. Right now, I am very grateful to have this time with Robert.”

Moore returns the respect as he does with all of these artists with whom he so clearly enjoys working. “What a pleasure it is to have him touching my life,” Moore says quietly. “He is very gifted and does whatever he is doing — whether it’s picking rock, digging trench, or painting a scene from China — with his whole heart. His work is such honest observation and strong draftsmanship. His color sense is beyond that of many people twice his age in this profession.”

In current times when it is not only acceptable, but often expected, for people to watch out for their own well being, the opposite notion is playing out in an old bean warehouse near Idaho’s Snake River. There, an admirable old-fashioned approach still applies — that of giving a helping hand.

Caleb Meyer

Caleb Meyer is a young painter working with Moore. Young enough, in fact, that it was his father who worked with Moore and Mensing at Camp Perkins. Caleb’s father was camp director there.

“He was a kind of ‘Uncle Robert’ to me. Our family lived up there in the summers, so we got to know the staff that way first,” Meyer recalls. “Later, Dad was working for Robert, helping in his studio with frames, and organizing things. I worked for him too, doing some landscaping, whatever he needed. It just felt right to me to be around Robert and his studio.”

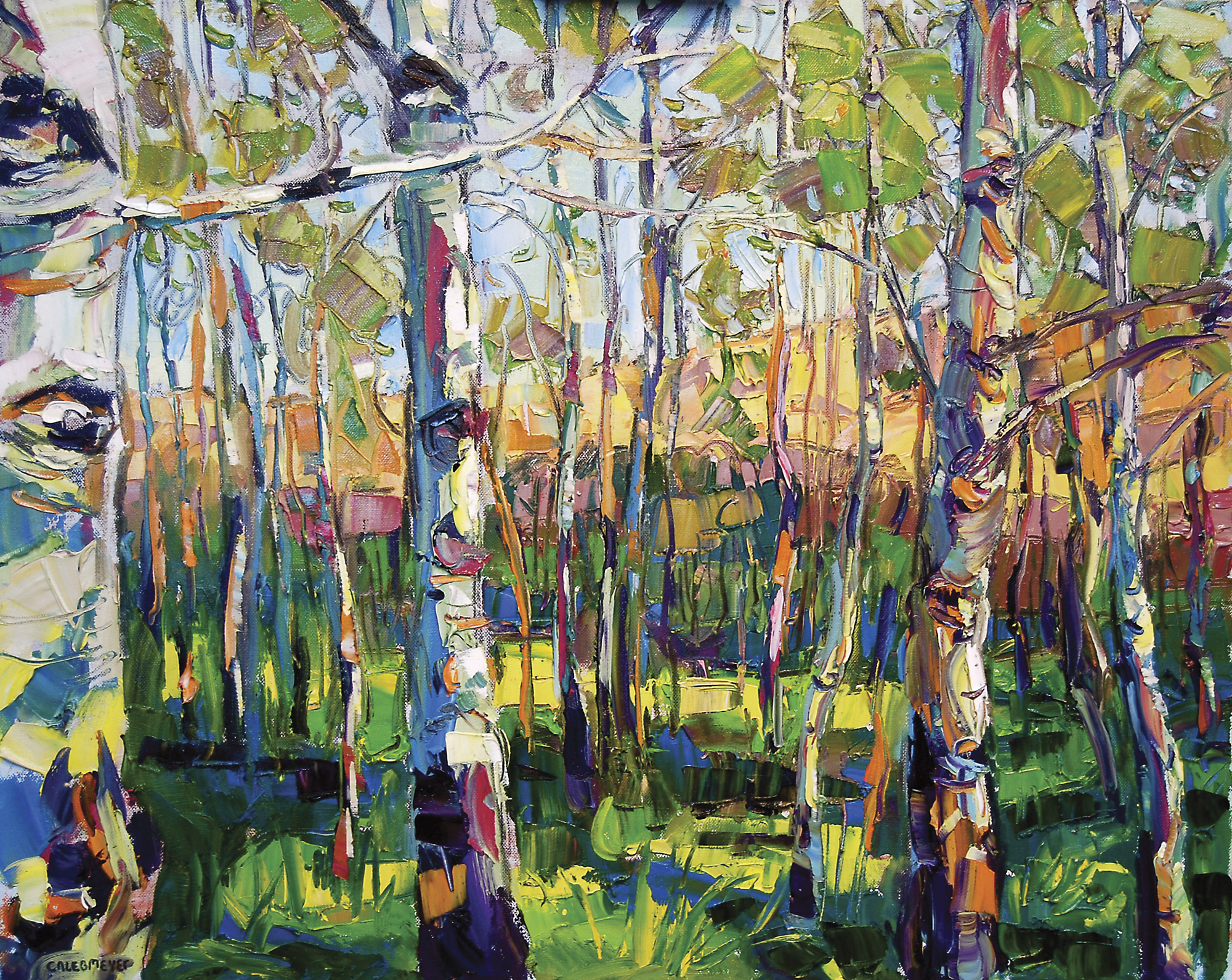

Even at his young age (only 27 years), Meyer is well known for his energetic approach to painting. His paint application is vibrant in color and motion. “I hope people see the action of the artist at work, the movement that each shape holds, not static marks, but something that’s actually in motion. Robert is so generous in sharing ways I might accomplish all this,” Meyer explains.

Meyer is currently teaching art at Twin Falls High School while studying with Moore. With a wife and two small children, he felt “it would be wise to find a steady income while I’m painting.” That may be so, but he is also selling work through a few galleries while balancing his teaching, his painting and his family. Moore’s voice softens and he chuckles a bit when he talks about Meyer’s work.

“Caleb is a very fun-loving person to be around and it’s interesting how that comes through in his work,” Moore says. “His motivation is not to get someone’s approval; it is not an expression to please men. He is expressing himself and he paints in the way he wants to paint. It is very difficult to teach someone to apply paint like he does, using a lot of patina and mixing it directly on his canvas.”

In a nod to the deep reciprocal respect between these artists, Meyer notes, “The fact that Robert and I study together shows in my work, of course, but I have always tried to find my own way. And, he is so encouraging of that. It’s important to understand my history with Robert, that I’ve known him since I was a boy. I’m kind of shy, really, and this same opportunity with anyone else might have been really hard for me. He’s such a good role model in so many ways. He gets artists together, brings the embers together, so we can fuel the fire with each other. I think maybe we’re all better painters for that.”

- Robert Moore

- “Bales and Blue” | Oil on Canvas | Robert Moore | 24″ x 30″

- David Mensing

- “Simply Trust” | David Mensing | Oil on Canvas | 11″ x 14″

- Caleb Meyer

- “Modern Transportation” | Caleb Meyer | Oil on Canvas | 40″ x 30″

- Francis Switzer

- “Vibrant Grove” | Caleb Meyer | Oil on Canvas | 24″ x 30″

- “Boundless” | Francis Switzer | Oil on Canvas | 16″ x 20″

- “Simply Trust” | David Mensing | Oil on Canvas | 11″ x 14″

- “Summer Morning” | Robert Moore | Oil on Canvas | 36″ x 48″

- “Three Roses” | Caleb Meyer | Oil on Canvas | 12″ x 9″

- “Rainy Street Scene” | Francis Switzer | Oil on Canvas |20″ x 16″

- “Vibrant Grove” | Caleb Meyer | Oil on Canvas | 24″ x 30″

No Comments