20 Aug Books: Writing the West (Fly Fishing 2009)

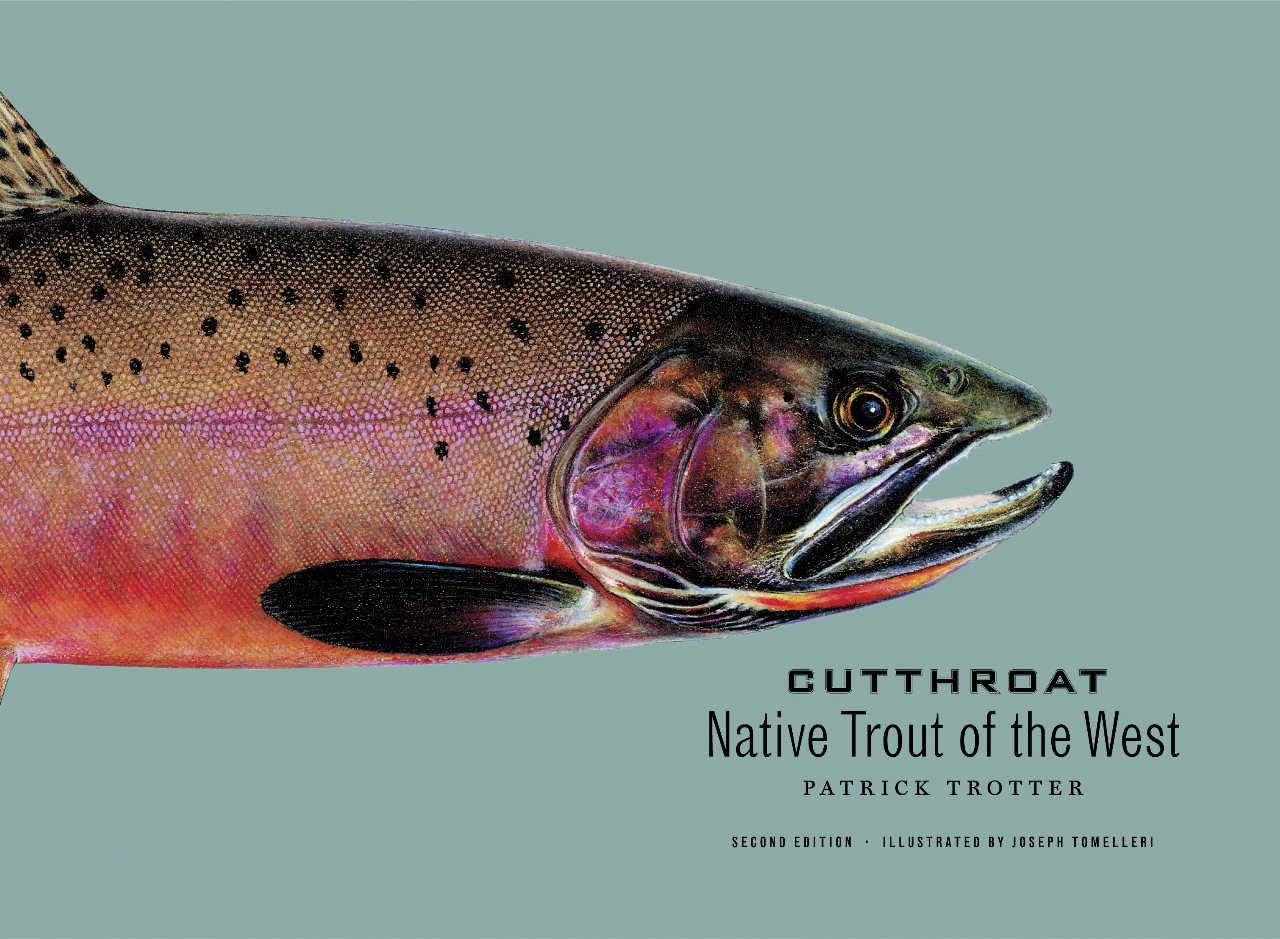

Cutthroat: Native Trout of the West

Patrick Trotter’s Cutthroat: Native Trout of the West (Second Edition, Revised and Updated; University of California Press, $34.95) is a thorough compendium on our local trout species. Well written and approachable, Trotter elaborates on the 14 subspecies of cutthroat trout recognized by Dr. Robert J. Behnke, professor emeritus at Colorado State University and the foremost authority on North America’s native trout. This revised and updated edition tells the stories, history and ecology of our favorite fish. Not only does Trotter write about the cutthroat’s past but also about the concerns and challenges of its future. Trotter presents just enough background on all topics to engage both novice and expert anglers with detailed footnotes, along with maps, tables and photographs, interspersed with tales of his own fishing adventures.

The red slashes across each gill-plate of the fish may have given it its name, but Trotter explains why they are not reliable guides to identifying the trout as a cutthroat. Trotter takes the reader millions of years back to begin the story of the evolution of the native trout. He presents two explanations of the trout’s emergence: Behnke’s belief that the native trout originated in the Pliocene or early Pleistocene time, more than 1.8 million years ago in the Northwest waters draining to the Pacific Ocean, versus Dr. Gerald R. Smith’s thought that the cutthroat came from the Bonnerville Basin much earlier, 8 million years ago. Analysis begins at the microscopic genetic level and then expands with a snapshot of shifting continents, accumulating and melting ice and altering weather.

The cutthroat trout’s allure magnifies as Trotter recruits the likes of Lewis and Clark and Jim Bridger. A young member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, Silas Goodrich, was the first white American to catch the trout on hook and line. Mystique surrounded Jim Bridger’s tales of catching trout from Yellowstone Lake and then immediately cooking them in the adjacent hot springs without taking the fish off the hook.

Each chapter, organized according to the specific species of cutthroat trout, opens with original illustrations by famed artist Joseph Tomelleri, followed with a lighthearted story or myth. After the historical and ecological dissertations, Trotter ends each section with concerns for the trout’s future as man disturbs the environment, resulting in habitat deterioration through restocking of non-native fish to exploring for natural resources. The cutthroat trout may be the most sensitive of all the trout to environmental disturbances, especially to the introduction of other trout. Trotter is saddened by the gradual disappearance of the native trout.

Cutthroat: Native Trout of the West abounds with information on a beautiful species of trout that is evolving in our changing Earth.

— Review by Stella Fong

Drift

Fly-fishing enthusiasts have been gobbling up adventure videos for the past five years. But with Drift (Confluence Films, $24.95), filmmakers Chris Patterson and Jim Klug have come up with a different kind of movie.

Patterson cut his filmmaking teeth with Warren Miller, shooting snowboarding and skiing movies for the past 17 years. But two years ago he was chomping at the bit to take the Warren Miller model to the sport of fly fishing.

Klug runs Yellow Dog Outfitters in Bozeman. He and Patterson met because their wives were college friends. A few years ago Patterson and his family moved to Bozeman and he began talking to Klug about his fly-fishing film idea. At first Klug wasn’t interested. There was already a flood of fly-fishing films hitting the market.

But the more Patterson talked, the more Klug got behind the idea. Drift combines Patterson’s filmmaking skills and Klug’s knowledge of fly-fishing personalities and hotspots around the world.

In Warren Miller fashion, Drift not only shows the action of fly fishing with creative cinematography, it also takes viewers to unique fishing spots: Andros Island, Bahamas; Deschutes River, Oregon; Bighorn River, Montana; Kashmir, India.

For the script, Klug and Patterson teamed with The Drake Magazine editor and publisher, Tom Bie, who wrote and narrated the film. For Klug, it was important the film have a storyline other than just catching fish. So many fly-fishing films have become simply about buddies going out and catching fish. Drift isn’t like that. At its heart, it’s a documentary.

The essence of the film are the personalities Patterson and Klug find in their various locations. From John and Amy Hazel, a husband-and-wife steelhead-outfitting team in central Oregon, to bonefishing legend Charlie Smith in Andros Island, Drift is about the unique people found in the fly-fishing world as much as it is about the action of fishing.

Drift is a film with broad appeal. From a unique soundtrack to breathtaking cinematography, Klug, Patterson and Bie have come up with a fishing movie that will captivate even those who have never lifted a fly rod.

— Review by Greg Lemon

If Fish Could Scream: An Angler’s Search For the Future of Fly Fishing

Paul Schullery, author of American Fly Fishing: A History, as well as author, co-author or editor of dozens of other books on angling, is widely viewed as fly fishing’s leading historian. It’s only natural, then, that when he sets out to answer questions about the future of fly fishing he focuses much of his investigation on the past.

What Schullery discovers — or at any rate, leads us to discover — in If Fish Could Scream: An Angler’s Search For the Future of Fly Fishing (Stackpole Books, $24.95), is that not only have angling culture and attitudes changed less over the last 100 or so years than we might think, but wherever our sport is going, it’s probably been there before. In the first of the book’s seven flawlessly composed essays he traces the adulation we shower on our national angling “celebrities” — the Lefty Krehs and John Gierachs of the world — to the quieter but no less intense respect that rural communities used to pay to their local fishing expert.

Angling tourism? The author reminds us that in the 1800s fly fishers from New York and Boston made far more arduous journeys to reach such angling “destinations” as northern Maine and the Adirondacks than a contemporary sportsman would have to endure to get to Argentina or New Zealand.

And just about every environmental concern, ethical dilemma and criticism of angling either faced or foreseen by contemporary anglers has also been with us for a long time. It was in 1819, for instance, when the poet and early anti-angler, Lord Byron, trashed people who fished for sport by declaring, “But anglers! No angler can be a good man.”

It is in his book’s final essay that Schullery, as much a philosopher as an historian, courageously and thoroughly grapples with the charges that fishing — and catch-and-release fishing in particular — is cruel. To his great credit, he takes the critics seriously, considers both sides of the argument with respect and offers up no pat answers. Instead he tells us, “Seeing all these people, and hearing their often eloquently made cases for this or that perspective on the ethical issues we’ve struggled with over the past few centuries when we hook a fish, I also see myself here and there among them, taking this or that view, on any given day, on any given cast, with any given fish.”

— Review by Paul Guernsey

Trash Fish

Greg Keeler’s latest book, Trash Fish (Counterpoint, $14.95), is a tale of a life lived in currents and eddies. It is a story of a boy who grows into a man dragging himself from the realities of living through fishing. Keeler’s storytelling is almost primitive. He writes what many think, but do not have the courage to say. His faults and failures are cast in real light and exposed. He wades out of his childhood pond in Oklahoma, bobs in the sea near Turkey as a Peace Corps volunteer and plies the rivers of Montana as a college professor at Montana State University.

Each story, poem and conversation is a short vignette, morsels that bait, hook and quickly release the reader. Keeler encounters a motley group of free spirits who are also swimming the whirlpool of life. Endearments such as Dr. Frankenstein, Cookie and the Captain are bestowed on characters who troll with Keeler through the rough waters of lament and guilt. Through it all, he belittles himself to buffer the pain. Through torrents of self-effaced suffering, there are splashes of raw beauty and insight.

Fishing is the common thread of his stories; trash refers not to the quality of fish but to heartfelt regret. His piscine life began as a toddler when his father tied him to the seat of their rental rowboat. From that point on he is strapped with the challenges of polite society, his true desires and his altered ego. He admits to an obsession for fishing, and unabashedly utilized any method to secure his catch. Through baiting, snagging, luring and fly casting, seizing the fish was all that mattered.

Fishing shields him from facing the realities of living. In an amorous moment, he watches the twitching of his fishing rod instead. He confesses to having “irrational carp worship” and dragging the “woes of his profession out on the stream.” Fishing eventually becomes an excuse to cheat on his wife and to ignore the illness and emotional pain she is experiencing.

He finally braces against his ride downstream as he faces the complexities within himself and those around him. When he does, Keeler finally catches his breath in a quiet pool in the river of life.

— Review by Stella Fong

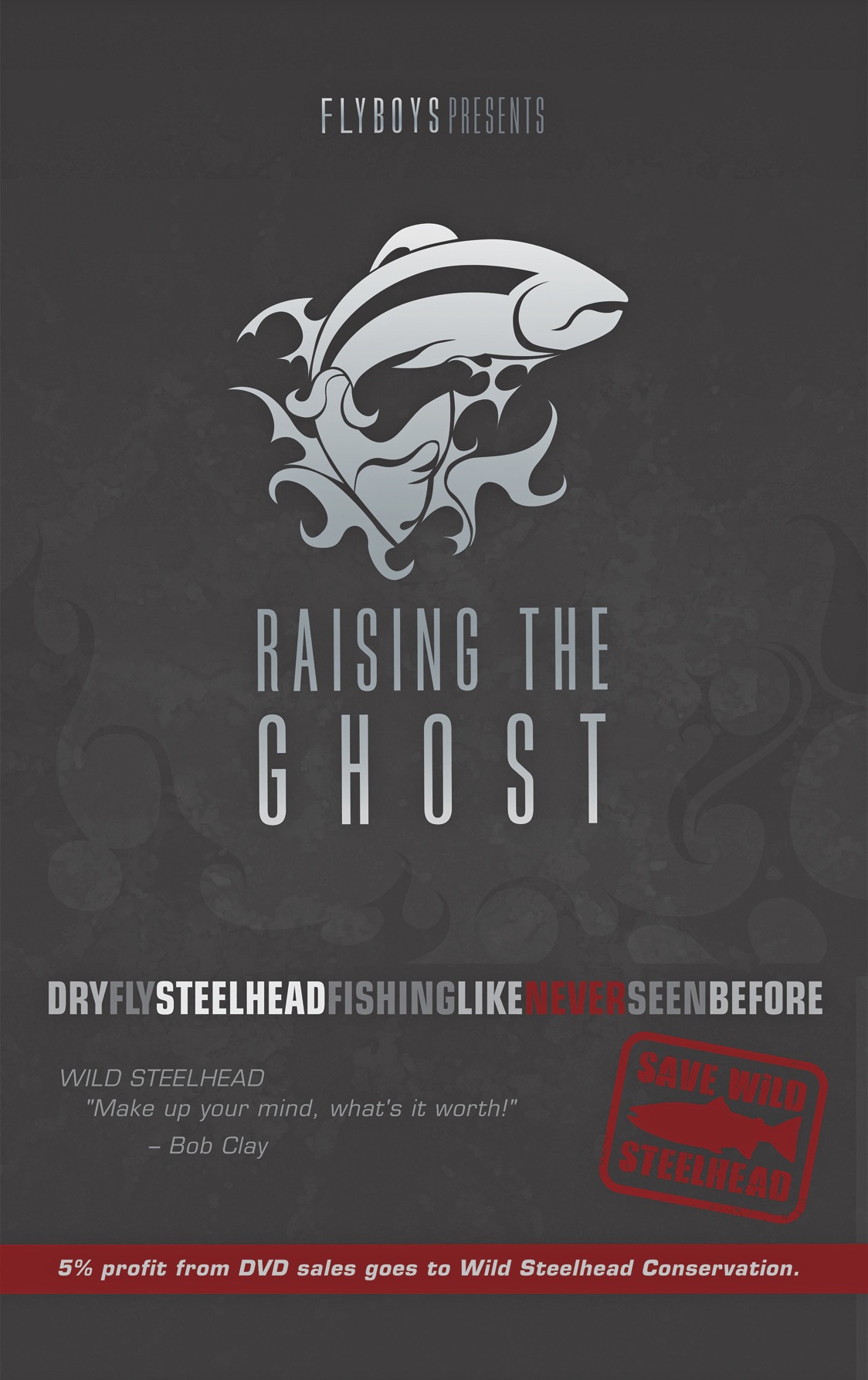

Raising the Ghost

Fly-fishing videos often struggle to show something new, but Fly Boys’ Raising the Ghost (RTG Pictures, $29.95) contains unique footage of steelhead trout rising to dead-drifted dry flies.

If you’ve ever fished for steelhead, you just reread that first sentence — but it’s true and it’s caught on film. Before I watched this video, produced by Paul Tarantino of Bozeman, Mont., I had no idea steelhead would sip mayfly imitations like a cutthroat trout. But on a remote tributary of the world famous Skeena River in British Columbia, they do.

Tarantino is the founding member of Fly Boys, a fly-fishing organization in Bozeman. He grew up in California surfing and fishing for steelhead.

Raising the Ghost chronicles the backcountry trip the Fly Boys took into the British Columbia wilderness in search of dry-fly munching steelhead. The trip took them by helicopter several miles up this mysterious river. (Tarantino refuses to say exactly which river the film was shot on.)

One of the most enjoyable aspects of the film is that it is about more than just catching fish. The depth of the film is its artful description of the plight of wild steelhead. Steelhead, like salmon, return to the freshwater streams of their youth to spawn. And like salmon, this makes them vulnerable. Wild steelhead populations have been depleted all along the West Coast. Massive hydroelectric dams, habitat destruction and the introduction of hatchery-raised fish have drastically reduced wild steelhead numbers.

Besides chronicling their trip on the remote and secret British Columbia river, the Fly Boys interview passionate steelheaders about the fish they love. The movie intertwines these interviews with fishing scenes from the Fly Boys’ quest for steelhead. After three days of struggling to catch fish, the group moves camp, makes adjustments and gets into several wild steelhead that, much like Montana trout, munch big mayfly drakes.

Raising the Ghost is a little more than one hour in length. And besides feeding the growing appetite for innovative fly-fishing movies, the Fly Boys are contributing five percent of the film’s profits to wild steelhead conservation.

— Review by Greg Lemon

Man vs. Fish

Fly fishing, like any complex sport, is a lifelong challenge for almost anyone who undertakes to learn it well. Yet, New Mexico fishing guide and author Taylor Streit is that type of gifted and single-minded fly fishermen whom other anglers seem to believe was born knowing how to cast, tie flies, find fish. Where’s the struggle in a life like that?

Ah, but Streit’s friends know him better. In his humorous foreword to Man vs. Fish: The Fly Fisherman’s Eternal Struggle (University of New Mexico Press, $29.95), Streit’s frequent fishing companion, novelist John Nichols (The Milagro Beanfield War) dishes details of Streit’s long-ago battle to learn how to write well.

“Compared to fishing,” Nichols informs us, “writing is like climbing Mount Everest locked in a straight-jacket and shackles.” As for Streit, “ … in the old days, Taylor didn’t know the difference between an adverb and a Dolly Parton. I mean a Dolly Varden.”

Streit himself, now that he can write almost as well as he fishes, is quick to disabuse us of the misconception that the fishing part is a snap for him, either. Fun, almost always. An adventure? Invariably. But easy? Come on; it’s fishing. The unpredictable rules, and something, large or small, is always going to go awry.

And that’s what Man vs. Fish is all about. Over the course of 30 lively and, for the most part, light-hearted, essays set in the Rockies as well as in sporting locations throughout the Caribbean, Mexico and South America, Streit entertains us with the ups and downs of an existence thoroughly dedicated to the outdoors. One of my favorites is “Ole Walter,” about the years-long efforts of Streit and his son, Nick, to land a huge and wary beaver-pond brown trout, and their surprising discovery about why the old rogue seemed so reluctant to take a fly.

Another terrific one isn’t a fishing tale at all, but the hair-raising story of how Streit once got lost in a storm and almost succumbed to exposure during a solo deer hunt (“Life and Death on the Sierra Alta”). And his Bahamas stories of casting to bonefish that had never seen a fly really got my heart going.

As a father, I was moved by the poignant theme of parenthood — its struggles and successes — that runs through many of these essays.

A final note: Man vs. Fish is an impeccably edited and beautiful book made even more so by Streit’s glossy color photographs, which are used liberally throughout it.

— Review by Paul Guernsey

No Comments