20 Aug Books: Writing the West (Arts 2010)

How to Build a Dinosaur

When I first read the back-cover copy of How to Build a Dinosaur: The New Science of Reverse Evolution (Plume Books, $16), I thought, “Come on already, create a dinosaur by reverse engineering a chicken? And without using what the layman has been told is that all-important ingredient for such Tinsel Town-type pursuits — namely DNA?” Well, in a word, yes. That is exactly what authors Jack Horner and James Gorman are saying. And what’s more, this new creature even has a name: the chickenosaurus. According to Horner it’s not only possible, but probable, given enough time. And that’s just plain fascinating, no matter where one lands on the should they-or-shouldn’t-they range of discourse.

Horner says early in the book: “Why couldn’t we take a chicken embryo and bio-chemically nudge it this way and that, until what hatched was not a chicken but a small dinosaur, with teeth, forearms, claws and a tail? I think we can. And I think we should. And if I have anything to say about it, we will.” Horner then proceeds to say something about it — for 200 intriguing and easy-to-read pages.

The professional accomplishments of the authors should be enough to convince readers that reverse engineering a creature based on the study of evolutionary development (Evo Devo) biology ain’t crank science. Horner is the world’s most famous living paleontologist, the recipient of a MacArthur “genius” award, professor of paleontology at Montana State University, and curator of paleontology at the Museum of the Rockies in Bozeman, Mont. He was also Steven Spielberg’s consultant on the Jurassic Park flicks. His co-author is no slouch: James Gorman has written several books himself, including two others with Horner, and he’s the deputy science editor of the New York Times.

The authors of this intriguing book know of what they speak. The book brims with interesting tidbits that I felt I should have known but didn’t: Birds are actually dinosaurs — of sorts. They are the closest link we have to the once-ubiquitous thunder lizards, more closely related to them, in fact, than are komodo dragons.

Perhaps the most exciting aspect of this new vein of study is that it has the potential to revolutionize science and provide invaluable insights into the evolution of genetic disease and birth defects. Though the Evo Devo research thus far is at the embryonic stage, the book addresses expected questions readers will have: What effect could this have on conservation? Who gets to decide if such a creature should be allowed to exist? Why bother with such a pursuit at all?

I personally like my chickens roasted, with gravy and spuds. But I’d forgo a tasty meal to see one of these new/old fangled birds up close. As long as it were leashed.

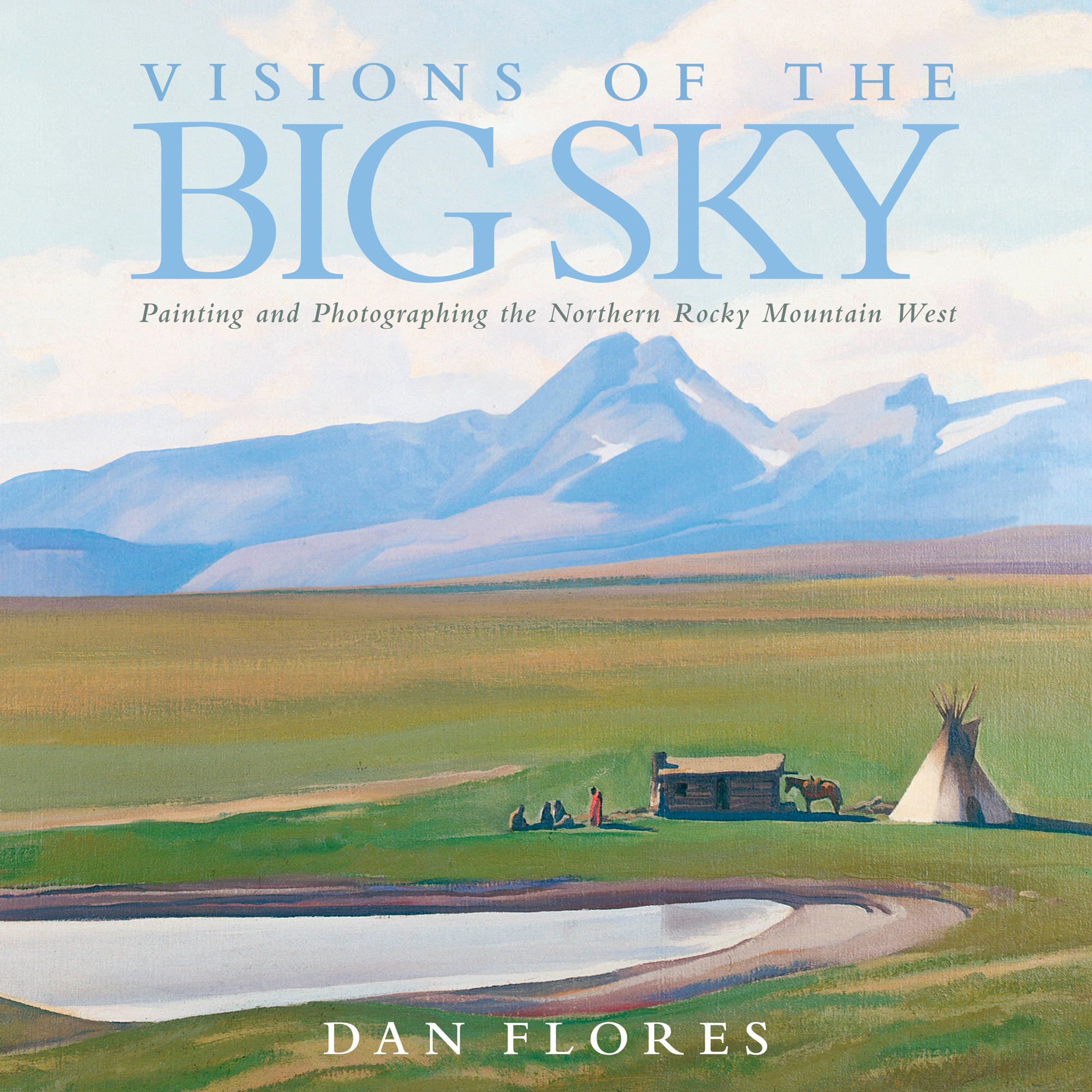

Visions of the Big Sky

University of Montana history professor Dan Flores opens his new book, Visions of the Big Sky: Painting and Photographing the Northern Rocky Mountain West (University of Oklahoma Press, $45), with the question: “How had it happened, and why, that the past two hundred years of history in the West has granted the states of California and New Mexico world-class legacies of photographers and painters, while reserving major music traditions for Texas and Washington? And why — at least for the past few decades — has Montana attracted primarily writers?”

A century and more ago, visual artists such as Charlie Russell, as closely associated with Montana as Georgia O’Keeffe is with New Mexico, helped establish the Northern Rockies as a visual-arts mecca. Flores says, “… this book is an effort to resurrect a regional visual legacy … But it is a visual legacy we tend to see today as if through a dusty window seriously in need of cleaning.”

Flores attempts to answer his big question by exploring the Northern Rockies’ rich legacy of visual arts through 248 pages of artwork and finely written essays. These essays, anchoring the book’s 25 chapters, guide us through the region’s artistic tradition as much as the book’s 140 color and black-and-white illustrations, melding Flores’s personal reflection with solid history to give readers a strong sense of the rich artistic diversity the region has experienced for hundreds of years. The final essay is a particularly strong entry in a book full of such offerings.

“In the End, What Was Charlie Russell Trying to Tell Us?” celebrates Russell’s contributions to the artistic legacy of the region while also acknowledging that he was an unrepentant nostalgist, convinced that the West’s best days were behind it. “As a result,” says Flores, “he spent his whole life looking over his shoulder.” And yet, Flores argues that today’s West is a stronger place precisely because Russell’s enormous body of work is tinged with a yearning for a bygone West. Russell no doubt would have been pleased — and pleasantly surprised — by this important new book.

The New Gray’s Fish Cookbook

On reading The New Gray’s Fish Cookbook: A Menu Cookbook (GrayBooks, $16), it’s apparent that author Rebecca Gray is a born foodie. Not a big deduction on my part, she says as much herself in the opening pages, but it’s her effortless and enjoyable writing style that’s the convincer. I’m not much of a cook, but I am a born eater (and reader). That she can keep me turning the pages is revealing, for only someone absolutely passionate about their food could keep me riveted to a cookbook.

Gray’s credentials are long and impressive, and her writing in this book, a revised, updated, and reawakened version of her classic Gray’s Fish Cookbook, first published more than two decades ago, is both refreshing and welcoming. That’s why the book is so much more than a book about cooking fish: It is a how-to guide by someone who’s a writer, a cook and a fisherman — and who appears to enjoy all three of her chosen tasks.

As she says in the preface, “ … good cookbooks have a personality and often are a straightforward reflection of a place or culture or of the author’s character. This cookbook is a reflection of me, here and now, not just me when I was thirty-something and wrote the first edition, but me as a sixty year old — and now long-time fisherman.”

Here we have an author who has rod-tested these fish and figured out the best ways to catch them, prepare them, pair them, and present them. Gray is authoritative in her approach to chapters, each covering types of fish in three primary sections: Salmon; Saltwater Fish (Inshore and Offshore, Fish from the Tropics, Saltwater Bottom Fish, and Shellfish); and Freshwater Fish (Stream Fish, Walleye and Pike, Shad, Catfish, and Smelt, and Bass and Panfish).

Each of the sections offers extensive menus, pairing the fish in question with secondary tasty treats. Consider this, the first menu from the first chapter (Salmon): Whole Poached Salmon If You Must, and its supporting cast: Green Mayonnaise, Salad of Zucchini and Yellow Squash and Tomato, followed with a Grand Marnier Rice Pudding.

We find out why she poaches her salmon in a turkey roaster. We also find out her opinion of over-the-top presentation: “… you may want to consider decorating it the way the guys in the tall white hats do. … But, in my opinion, decorating is completely unnecessary if the salmon is going to be served to fishermen; they like the way it looks — dead-glaze eyeballs and all — just fine. The rice pudding looks most attractive when served in a glass bowl.”

There you have it: simple, straightforward, serviceable — keeping the fishermen in mind — informative, and above all, serious without taking itself too seriously. It’s only after you’ve read the entire book that you realize you’ve been thoroughly entertained, and maybe learned something along the way. Hey, wait a minute … maybe there is something to this cookbook thing after all.

The National Parks

It’s a doorstop, it’s a weapon, it’s a honking big companion volume to Ken Burns’ recent documentary masterwork! It’s all of the above, but mostly it’s the beautiful new book, The National Parks: America’s Best Idea, An Illustrated History (Alfred A. Knopf, $50), by Dayton Duncan, with a preface by Ken Burns.

The weighty book is image rich — 440 color and black-and-white illustrations, including photographs, artwork, and maps, plus a removable full-color map — and caption heavy, positive attributes with book readers in mind. I defy anyone to flip though its pages and not pause at each and every page and marvel at what is there.

The book is billed as a companion volume to the 12-hour PBS series, and that’s swell, but that sort of marketing speak is misleading, for this book is a sound compendium that was intended to stand on its own. One would be mistaken in thinking he won’t need the book if he’s seen the series (well worth the viewing time, by the way). On the contrary, the book goes places the film can’t, and contains materials that weren’t included in the series.

The book offers detailed narratives describing the process of acquisition of each of the parcels of land by the national park system, the significance of each parcel to the system and, in a broader scope, to the nation. We’re treated to in-depth introductions to the people, famous and not so, who helped establish and continue to protect the parks — something we learn is an ongoing battle against special interest groups that would do the parks harm — and we’re given six extended interviews with people whose lives have been altered and shaped by America’s natural landscape, among them noted authors Terry Tempest Williams, Nevada Barr and Paul Schullery.

Here is the entire long, involved, and utterly engrossing history of the formation of the nation’s national park system. Described on the dust sleeve as “ … an idea as radical as the Declaration of Independence: that the nation’s most magnificent and sacred places should be preserved, not for royalty or the rich, but for everyone.”

In his preface, Ken Burns says the documentary film series “grew out of experiences and emotions and attitudes formed and shaped by more than three decades of trying to get to the heart of a deceptively simple question: Who are we?” And by “we” he means Americans. This book goes a long way toward defining what it is he’s after.

Of Rocks and Rivers

In her latest collection of essays, Of Rock and Rivers: Seeking a Sense of Place in the American West (University of California Press, $24.95), Colorado State University Professor of Geology Ellen Wohl, says, “I am one of those people with an intense attachment to place — in my case, the whole interior of the American West from the hundredth meridian to the crest of the coast ranges.”

That’s a sizable attachment, to be sure. The 14 essays guide us along her journey from a Midwest-born budding naturalist to a full-blown professional geomorphologist and lover of the West. Early on she writes, “The West is not a pristine wilderness, for people have been altering natural processes here for millennia. This apparently simple fact has for me had an enormous repercussion: I recognize now that there is no unspoiled source of truth or life. There is no western reserve. And this makes all the difference.”

To be sure, this is no dry tome on geology and the minutiae of rock formations. Rather it’s a highly readable book of personal essays meant not just to reach but to affect a wide audience. Much like the constant and reassuring presence of a solid-rock landscape and the steady, gentle pressure of flowing water, Wohl’s lyrical writing is guided by a strong hidden force, what she feels is an urgent need to ensure the protection of the precious and dwindling natural resources of the West, not from evolution, but from harmful, premature change.

Anyone interested in the West, be they a resident or a curious onlooker from an armchair back East, would be hard-pressed to find a series of such readable, but vital, essays.

No Comments