24 Jul Books: Writing the West (Arts 2013)

Todd Wilkinson’s Last Stand: Ted Turner’s Quest to Save a Troubled Planet

Todd Wilkinson’s Last Stand: Ted Turner’s Quest to Save a Troubled Planet (Lyons Press; $26.95) leads me to suspect that Ted Turner bears the enviable trait of not giving a whit about what people say or think about him. What he does care about, as we learn in Wilkinson’s engaging book, is nothing less than planet Earth. And he’s convinced he can effect positive change in the dismal eco-future we all face. But only with everyone’s help.

Tall order? Maybe, but no one can accuse Ted Turner of doing much in his life by half measures. We are, after all, talking about the second largest private landowner in North America, a man who possesses the deeds on more than 2 million acres; the man whose bison herd, some 56,000 strong, roams six Western states; the man who counts the 113,000-acre Flying D Ranch outside Bozeman, Montana, as a getaway home.

Last Stand explores this green-minded man’s journey even as he beckons others to follow. It’s a powerful read filled with ruminative, envy-making and heartbreaking moments. And through it all, Ted Turner comes across as a man for whom the phrase “far beyond driven” could have been invented. He has been called the “Mouth of the South,” a knee-jerk provocateur, tactless, a man who will say anything in front of anyone, a lefty who is conservative in his business practices.

And while those designations may be apt, Turner prefers instead the titles he has worked quietly for decades to earn: eco-capitalist, citizen environmentalist, anti-nuclear weapons crusader, humanitarian agitator, friend of bison, protector and bequeather of land, philanthropist and many others.

The book shows just what positive changes one person with a steely will and unwavering vision — and backstopped with deep pockets — can make. Is it possible for one man to save the world? Probably not, but with effort and luck, it might just be possible for one man to exert enough influence to help everyone else contribute to the cause, to put their own shoulders to the wheel.

And that may well be Last Stand’s greatest use — as inspiration that precedes motivation, which in turn leads to action. Turner himself voiced this sentiment in his foreword (titled “A Time to Rally”): “The world is in peril and it’s time for all of us to put our rally caps on. This is not a Liberal or a Conservative issue. Don’t believe it when the folks on television try to portray it that way. … If there’s anything that Last Stand does, I hope that it will inspire you to consider that, by working together — as neighbors, as businesspeople, as citizens and inhabitants of the only planet in the cosmos known to contain life — we have the capacity to change the trajectory of the world. Of course, we have no other choice.”

Through a relationship that has lasted from 1992 to the present, Wilkinson has worked to unnerve the mogul. By his own admittance, Wilkinson’s questions and button-pushing made Turner uneasy, but to their credits, both men stuck with it. They delve into what made Turner the complicated man he is: from a childhood in which he was sent away to boarding school at age 4, to a “painful relationship” with his father, on through his years racing yachts, building a media empire and his marriage to Jane Fonda. Mixed in was a deep and lasting mentorship by Jacques Cousteau, and his powerful and affecting friendships with such heavy hitters as Mikhail Gorbachev and Tom Brokaw. Along the way, he transforms from a young professional embracing the me-first ideology of Ayn Rand into someone who today believes that “how we treat the Earth is the biggest expression of our success or failure as a society.”

Wilkinson was also able to prod the notoriously private Turner into deep reflection, into really thinking about his vision, a word neither man uses lightly here. As a self-professed “environmentalist, eco-capitalist, humanist, father, granddad, and landowner …,” Turner’s vision for what the earth needs — and doesn’t need — is both complex and simple:

“Imagine that it’s the bottom of the seventh inning and the home team — that’s the side playing for preservation of Mother Earth and civilization — is down by a couple of runs. The opposing team has an imposing lineup. The names on the backs of the jerseys are: Apathy, Cynicism, Greed, Sloth, Violence, Cruelty, Hatred, Intolerance, and Selfishness. All is not lost — yet — but in order to win, we as citizens watching from the bleachers need to rise to our feet. It’s time that we band together, make some noise, suit up and become heroes, and remind others who are trying to mount a comeback that we’re on the same side.”

Thankfully Ted Turner is concerned, wealthy and willing to play coach, a rare combination these days. Let’s hope it’s enough to get people to take to the field. Put me in, coach.

The Last Outlaws: The Lives and Legends of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid

The Last Outlaws: The Lives and Legends of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (New American Library; $26.95), by Thom Hatch, is the latest — and for my money, the best — book about two of America’s most notorious and beloved outlaw sons, among the last in a long line of true American outlaws, at least of the Old West variety.

Butch Cassidy, a.k.a. Robert Leroy Parker, and the Sundance Kid, a.k.a. Harry Longabaugh, were men who chose to steal from others rather than earn money in less destructive ways. Though there was little honorable about them, and even less to revere, in the context of the rapidly shifting American West, they were a fascinating pair of unapologetic, unrepentant and unrelenting outlaws, freely choosing — and reveling in — the lives they led.

Both men were raised in sound households, Parker in a large Mormon family in Utah and Longabaugh in Pennsylvania. They both sampled the outlaw lifestyle as young men working as ranch hands. Later they formed a friendship and partnership that the movies got only partially right. But the well-known facts remain: They led the notorious criminal supergroup, the Wild Bunch, pulling off some of the most daring and brazen bank robberies and train hold-ups of their day.

Much of their success was due to the extensive planning that went into each job. This was also why they were so successful in hoodwinking their prey, primarily wealthy railroad owners and bankers. And they were also exceptionally good at eluding both the law and the notorious Pinkerton Detective Agency’s finest operatives.

The Wild Bunch, and Cassidy and Sundance in particular, captivated the awestruck public’s attention — Americans love their bad boys, particularly if they’re (allegedly) running the Robin Hood routine — and led the law on a merry, years-long chase filled with hijinks and narrow escapes (and sometimes captures), from Wyoming to Colorado to Utah, down to Texas and beyond.

While Hatch does his best to discern fact from fiction, instead of drawing a line in the sandy ground of history, to his credit he admits there’s a whole lot about these two men that’s unknown and may well remain that way. And in this page-turning dual biography, the author dishes it all up and lets the reader dwell on the possibilities and probabilities. And there are plenty of them to go around. Maybe that’s why Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid persist today as much fact as legend.

High and Inside

High and Inside (Bangtail Press; $16.95), by Russell Rowland, is the moving story of a former Red Sox pitcher who can’t seem to get out of his own way, and carries a big problem with alcohol that ping-pongs him back and forth between regret and dumb decisions that result in more regret, followed by more less-than-impressive decisions. But he has a few saving graces that endear him to the reader — good thing, as he can be a tough nut to crack.

He has an attitude problem, a drinking problem, an impotence problem and a number of other personality elements that, added together, make for good reading. We all love to rubberneck at a car wreck, and reading High and Inside often feels like a six-car pile-up. But Pete Hurley’s a good-hearted man, he likes dogs and he’s not afraid to keep picking himself up — ultimately, what’s not to like?

The fact that it’s told in first-person point of view is especially effective, as it helps the protagonist justify and defend his destructive behavior. Only when he is forced to step back and recognize these patterns does Pete begin to entertain the notion of life without booze.

High and Inside is a complex novel with a large character cast and a whole lot of weighty themes: addiction, loneliness, anger, marital woes, death. Rowland delivers them right across the plate. He also does an exceptional job in depicting how people deal with their respective — and all-too-real — lives.

This is not to say that the book is a heaping helping of depressing reading — far from it. The story keeps moving along at a just-right pace, there’s plenty of humor and quirkiness, and it’s all held together with Rowland’s easy style. The most tender moments often come when that sense of humor shines through, as on page 150: “Arlene looks at me with that goofy expression drunk people get, halfway between an orgasm and a coma.”

High and Inside is just playful enough that no matter how heavy the action gets, Rowland doesn’t cheap out and turn it solely into a depressing study of a man with a mounting pile of problems he chooses to ignore. By the end, though I’d trekked through a whole lot of emotional landscape with the characters, and though sometimes I wanted to throttle Pete Hurley, the characters and their lives are so well rendered that I can’t help but want to know what happens next.

Faith of Cranes: Finding Hope and Family in Alaska

Faith of Cranes: Finding Hope and Family in Alaska (The Mountaineers Books; $16.95), by Hank Lentfer, depicts the author’s unease with the churning encroachment of civilization on the world’s natural places, particularly his native rainforest-coast Alaska. Faith of Cranes is also a rich series of insights, revelations and ruminations on becoming the sort of person the author eventually realizes he needs to be. The reassuring and predictable migratory patterns of sandhill cranes provide a comforting backdrop and touchstone for the author, in both a literary and literal sense.

As a young man, Lentfer’s father recognized the author’s deep attachment to the place they’d always hunted together: “It’s like falling in love with a beautiful woman who is being abused and you can’t do anything about it.” The reference, of course, is to a dominant theme in the book — the slow ravages of nature brought about by man’s hunger for … everything. Passages alternate throughout the book, from those explaining sandhill cranes, their lives and migratory patterns, to the author’s own struggling, often hard-earned route from youth to a wide-ranging, insular loner.

Lentfer’s youthful ideals slowly expand as he becomes more distressed by what he sees happening to his beloved natural world, close to home and beyond. He perceives these changes not as inevitable but as something he must prevent, and he does try. It seems that once he becomes bitten by conscience, however, he spends his life in agitation by the destruction of beauty for the sake of money, the crushing grind of humans’ need to destroy nature to fill a gas tank or have dandelion-free lawns or wear designer togs. (And who can blame him?)

So he fought (and continues to fight) the “good fight,” jousting politicians, defending a shrinking natural world and largely ignoring the fact that there was much inevitable goodness and beauty in the world, too. It was there all along, naturally, but to find it Lentfer needed to follow a new path of growth and learning. And it was his wife’s pregnancy that provided the helping hand he needed.

Of course, Lentfer’s prose is more eloquent than that — much more, as it turns out. And because of it, Faith of Cranes is a richly written, moving account of how one deeply considered man learns to accept and not accept, to live with and to refute, and to come to terms with, his own life. It is not an admission of failure any more than it is a vindication or a well-wrought I-told-you-so.

It is one man’s wholehearted, sincere pursuit — sometimes without even knowing what he was pursuing — of the first, last and best things we all should hold allegiance to: faith in love, beauty, and hope in nature, in goodness, in the promise and necessity of choosing one’s attitude and thus determining one’s direction.

Much of Faith of Cranes’ most promising meaning is summed up in this late-in-the-book sentence: “If lamenting the loss of beauty is itself a beautiful act, can beauty really ever diminish?” Doubtful, especially if we are fortunate enough to have writers such as Hank Lentfer expressing his lamentations, acceptances and ultimate rejoicings.

OF NOTE: Books, Music, Movies & More

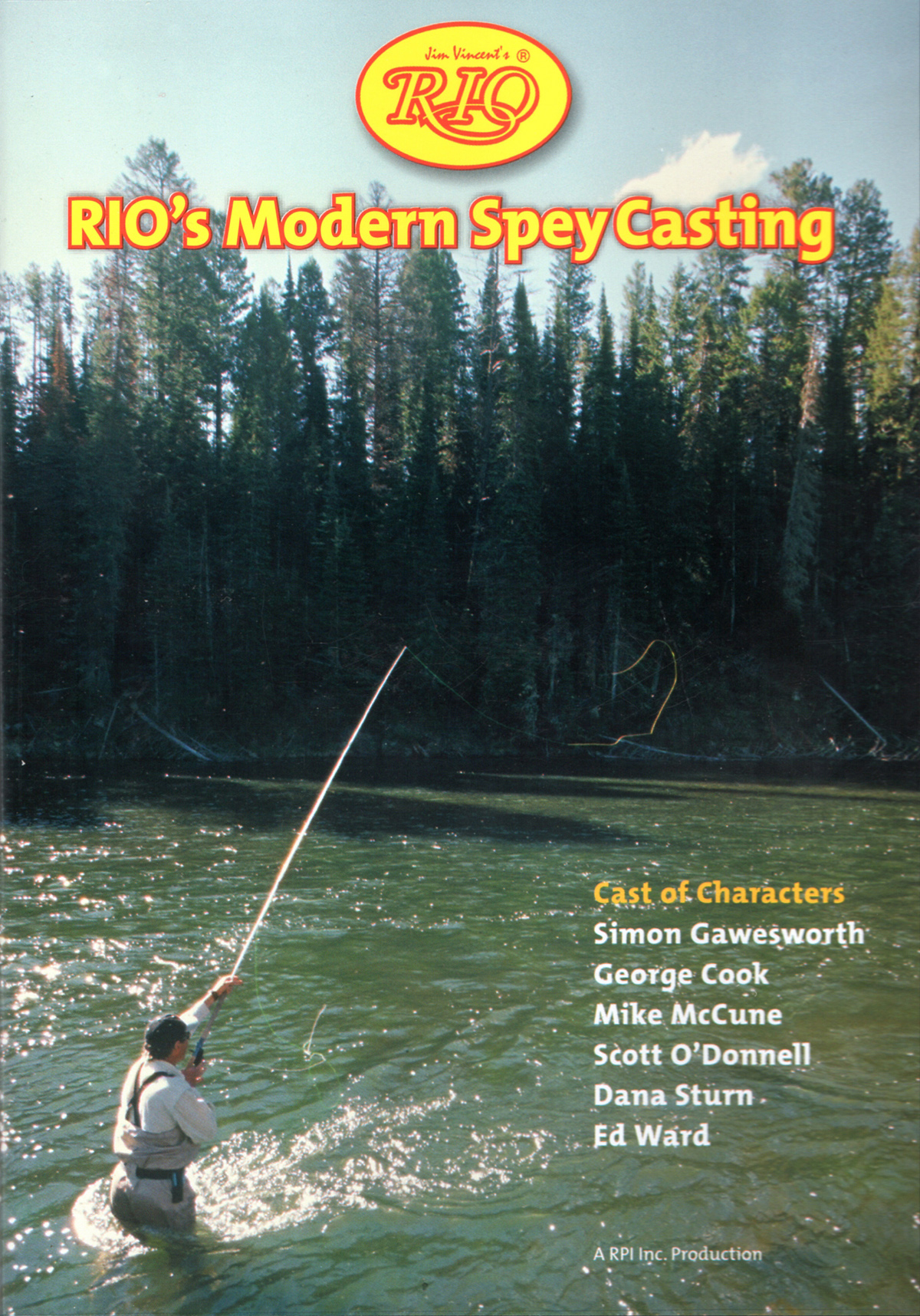

The Drake: From the price tag on the cover (“Five Bucks” underscored with “$10 for Bait Fishermen”), it’s obvious The Drake is not only all about fly fishing, it’s also a quarterly magazine that manages to be many things at once — bold, inventive, real, educational, irreverent, cheeky. At 120 pages, the Spring 2013 issue is a well-laid-out whopper sporting a solid balance of fish porn and river shots, and stuffed with top-shelf articles — and a whole lot more. If you’re an angler (non-bait!), or know one, this is the best $18 you’ll spend this year.

“Home on the Range” (Riders Radio Records; $20), by Riders in the Sky and Wilford Brimley (yep, that Wilford Brimley!), is a brand-new full-length CD offering a dozen tasteful tracks with stirring vocals by Wilford Brimley, everyone’s favorite grandfatherly cowboy figure. And he’s backed by those four crackerjack musicians known as Riders in the Sky. The disc contains all the hallmark elements listeners expect from Riders in the Sky — tight harmonies, heartfelt, melodic lead vocals, top-tier musicianship. Some of my favorite songs tend to have an unexpected jazzy edge, with playful vocals by Brimley, such as on “Won’t You Ride in My Little Red Wagon,” “Fraulein” and “Roly Poly.” The cowboy actor’s singing voice is as memorable and pleasurable to listen to as his famous speaking voice. And that’s just one of the many elements that make “Home on the Range” such a pleasure to spin, over and over again.

Photographing Montana (Countryman Press; $14.95) is exactly what that succinct title claims: A book all about photographing the Treasure State. Beginning with numbered maps that correspond with a detailed table of contents, the authors, Cathie and Gordon Sullivan, usher the curious from Glacier National Park’s lofty peaks to “The Breaks” and beyond. The book takes readers through the entire state in 112 full-color, glossy pages packed with drop-jaw shots of vistas, flora and fauna, all the while doling out grounded advice for novice and experienced shutterbugs.

I’m not normally fond of books about books, especially books that tell me what I should be reading. But in the case of A Sportsman’s Library (Globe Pequot Press; $18.95), I’ll gladly make an exception. The subtitle tells the reader just what to expect in these 255 pages: “100 essential, engaging, offbeat, and occasionally odd fishing and hunting books for the adventurous reader.” Each chapter consists of a couple of pages about each selection (plus suggestions for further reading), all divvied into three big sections: “Fishing”; “Wingshooting”; and “General Hunting, Guns, Travel, Mixed, and Miscellaneous.” The danger here is that I find myself marking every other page, noting all the enticing finds I’ve not yet read. But then again, that’s the very point of this book.

Low & Clear (Finback Films; $25), a feature-length documentary film by Tyler Hughen and Kahlil Hudson, has raked in a number of well-deserved awards and high-profile praise. Two longtime fishing buddies meet up to fish together after many years apart. But one just wants to fish for the sake of fishing, the other sees the pursuit as something more spiritual. The film’s lesson is that neither — and both — are correct. And as with all art, it offers viewers and the men profiled more meaning than the surface would indicate.

The tale here is compelling enough to warrant repeated viewings, but the cinematography is drop-jaw stunning and worth the price of admission by itself. It also makes you want to fish, to get out and about in the beautiful backcountry of Canada, Colorado and the Texas Gulf Coast, all locations covered in Low & Clear.

It Happened in Yellowstone (TwoDot; $14.95), by Erin H. Turner, is a gripping collection of remarkable events that helped shape the history of the park. The 26 chapters, arranged chronologically from its geologic formation 600,000 years ago to today, touch on high points throughout the park’s history, including Joe Meek’s escape from the Blackfeet, the formation of the world’s first national park, efforts to save the buffalo, a stagecoach robbery, grizzly attacks and much, much more.

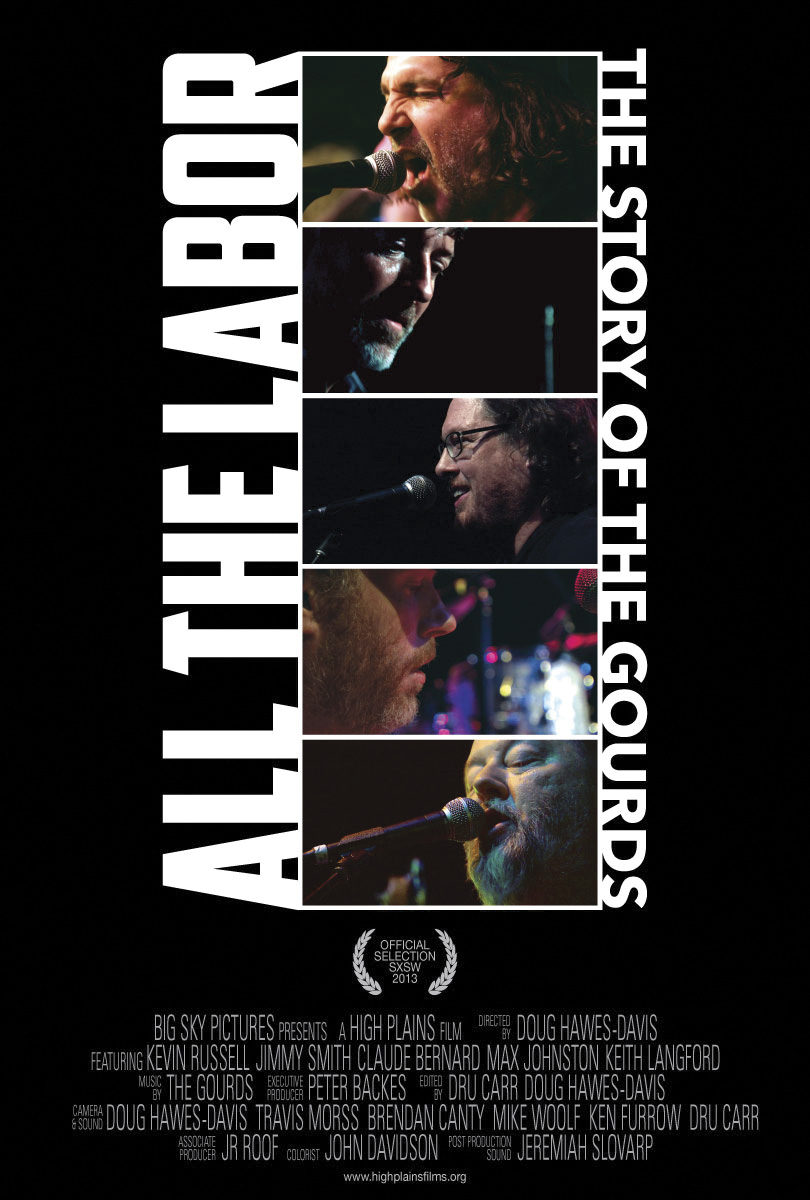

All the Labor (High Plains Films; $25). The new documentary about the Austin, Texas-based band, The Gourds, by Montana-based High Plains Films, is a groovin’, greasy feast for the ears, eyes and feet. It provides an education for the uninitiated; it’s visually entertaining and offers tons of live footage for the hardcore Gourds fan. Newbies will find themselves unwittingly tapping toes and bobbing heads as they discover the hypnotic and whimsical entity that is The Gourds.

Candid interviews reveal The Gourds — a 19-year-old band that keeps on, despite deserved commercial success — as a collective of unpretentious friends who do what they do because they love it and can’t imagine not doing it. The Gourds just keep rattling around, making good music for themselves and for their fans. As one of the band members says, and I’m paraphrasing, but not by much: “Man, are we lucky or what?” So are we all. Long live The Gourds.

A Montana Journal (Riverbend Publishing; $24.95), by photographer Christopher Cauble, serves double duty — as a journal and as a reminder of what a truly awesome and awe-inspiring place Montana is. The 36 color photos interspersed throughout the 200-page hardback journal are supported by a smattering of inspiring and appropriate quotes from the likes of Steinbeck, Stegner and others. This rugged hardcover also sports a sewn binding, a ribbon marker and lined matte-finish pages. It would make an ideal gift — for yourself or someone you know who loves Montana. And if they don’t yet — they will.

No Comments