24 Jul Rethinking Indian Art

OFTEN, THE PHRASE “AMERICAN INDIAN ART” EVOKES visions of traditional beadwork, the intricate patterning of powwow regalia, geometric designs on ceramics of the Southwest, or the distinctive figures of old ledger art. We imagine teepees and horses, feathers and cradleboards.

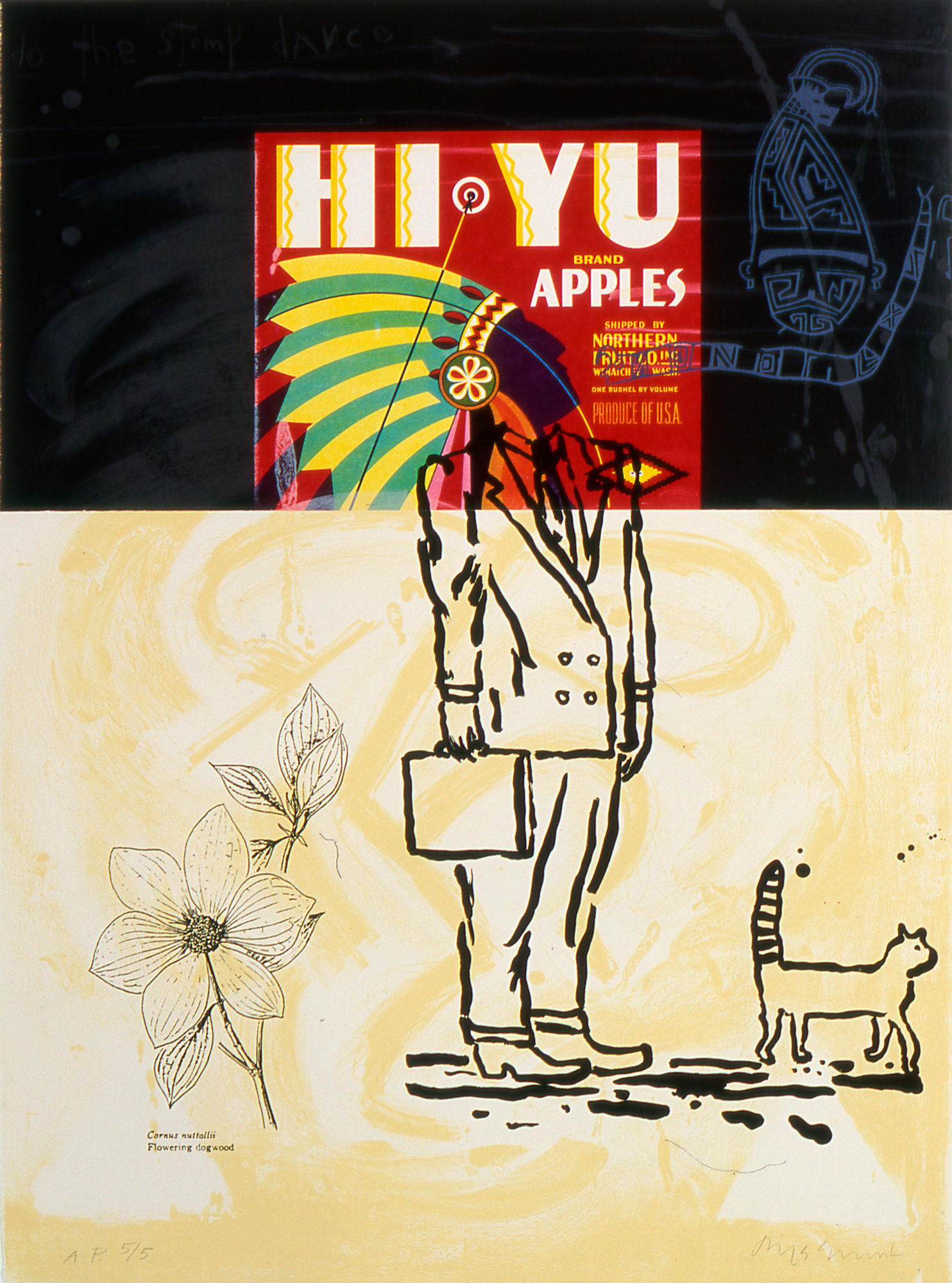

And yet, if American Indian art is only about the traditional, historical aesthetic, where does that leave George Longfish’s distinctly pop-art style, or Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s wry and scathing lithographs? What of Joe Fedderson’s blown glass, or Corwin “Corky” Clairmont’s ironic, modern collage?

Clairmont, a Salish-Kootenai artist and professor, says, “The ‘real’ Indians did not all die out sometime in the 1850s. By exhibiting contemporary Indian Art, you have to recognize that Indians are alive and active participants in life today.” And this is where the Missoula Art Museum comes in.

“We know of only a few other museums in the country that have a similar concentration of this kind of work,” says Laura Millin, executive director of the Missoula Art Museum, referring to MAM’s Contemporary American Indian Art Collection. We’re standing in a bright, airy gallery on the museum’s second floor, surrounded by a sampling of work from this collection. As we chat, Millin strides around the hardwood floor, straightening a frame, pausing to contemplate a work before answering a question.

Numbering over 120 pieces and counting, the Contemporary American Indian Art Collection houses the work of emerging Indian artists, including the beadwork of Molly Murphy and the fiber art of Marie Watt, as well as that of well-established Native artists, like Quick-to-See Smith, Longfish, Clairmont, Fritz Scholder, Ernie Pepion, and Kevin Red Star.

This earlier generation arrived on the Modern art scene in the ‘60s and ‘70s, redefining what it meant to be an Indian artist. They came from diverse backgrounds — some grew up on hardscrabble reservations, others in cities — but all were drawn to art, and the power that lay within it. By combining modern European artistic techniques with aesthetics, beliefs, and experiences from their own backgrounds, they created work that spoke about both the past and the present. “Contemporary art,” says Clairmont, “captures the current values, politics, beauty and ugliness found in our lives.” Today’s modern Indian artists “have important statements to be made and a rich culture to draw from, emanating from over 10,000 years of living on the North American continent.”

Here in this gallery on an overcast Wednesday afternoon, those statements and culture practically sing from the white walls. Molly Murphy’s vibrant red tapestry, Forced North, depicts in beadwork the topography of western Montana, and the path taken by the Nez Perce as they were driven out of their homeland. Joe Feddersen’s glass creation, Fish Trap II, abstractly represents the equipment traditionally used by Northwest tribes for fishing. In Modern Times: America, George Longfish portrays an Indian dancing in full regalia, overlaid with words like “White Bread” and “Apple Pie” and “The American Dream.” Everywhere there are brilliant colors, and everywhere there is a blending of history and present-day, personal and political.

As a contemporary art museum, MAM’s mission is to showcase current work from a wide variety of artists, and to grow and change along with the times. “Thirty years ago, museums were just sort of art depositories,” says Ted Hughes, MAM’s registrar. “Today, though, we’re in touch with how people represent the things they have to say, and how communities respond to that.” Located as they are in Missoula, MAM has the opportunity to network with artists from throughout the Northwest, and continually update their collections and exhibit new work. Steve Glueckert, curator of exhibitions at MAM, is thrilled by the idea that the museum is constantly changing and growing as artistic trends shift and new artists arrive on the scene. “I think the museum is something that is organic, the institution itself, and while we know we’re good, we know we can always be a better museum tomorrow.”

Later, down in the museum’s overflowing vaults, Glueckert and Hughes show me some of the pieces of the collection that aren’t currently on display. After talking about Anne Appleby’s quiet colorscapes, Jason Elliot Clark’s stunning prints, and a recent acquisition from Kevin Red Star, Glueckert steps back to reflect on the honor — and the responsibility — of overseeing such a remarkable collection. After a moment he reiterates his earlier thoughts: “There are always better ways to feature art. There are always better ways to celebrate people, and contribute to culture.”

It was with this philosophy in mind that MAM entered into a conversation in 1998 with Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, an enrolled member of the Flathead Nation and a widely acclaimed artist. She approached the museum with an idea: establish a collection of contemporary American Indian art, which would live at and be showcased by the museum. To get the ball rolling, she donated several pieces from her personal collection, including her own work and that of other Indian artists. With the help of a cultural trust grant from the State of Montana, the Contemporary American Indian Art Collection was born. According to Hughes, “We had very few artworks by Indian artists prior to the establishment of the collection, only two as far as I can tell.” In a little over a decade, the collection has grown to be one of the largest in the country.

This growth wouldn’t have happened without the support from two important communities: art aficionados in western Montana, and American Indian artists themselves. In 2006, as MAM was wrapping up a major expansion and renovation project, Millin met with elders representing various tribes throughout the region, as well as numerous Indian artists, and asked for their thoughts about the creation of a gallery dedicated solely to contemporary Indian art. With their input, and the help of a gift from one of MAM’s board of trustees, the Linda Frost Gallery was dedicated.

“It was a little controversial,” says Millin, “because some artists were worried that this gallery would be relegating Indian art to a dusty little corner, which is what usually happens to Indian artists.” That “ghettoization” of Indian art in many museums often perpetuates the idea that the work is somehow unequal to that of other artists, or that the work must be singled out as different.

But at MAM, two factors help dispel those concerns: work from the American Indian collection is featured throughout the museum, not solely in one gallery. And the one gallery that is dedicated to Indian art is spacious, beautiful and centrally located within the museum. “We have yet to work with an artist who, once they’re here, doesn’t love this space and feel fine about being here,” says Millin. She believes that the gallery and the collection have been successful because “we’re promoting that yes, they’re Indian artists, but first and foremost, they’re incredible artists, period.”

Clairmont, who has been involved with MAM for several years, says he appreciates and respects the museum’s approach to both the collection and the way they present it to audiences. “It is the responsibility of a museum to provide an informed educational opportunity to the public. I feel that their collection includes Indian artists’ works based on merit and educational value and not just because a ‘Red Man’ created the artwork.”

Ultimately, Millin says, it’s about making the commitment to American Indian artists, and to presenting their work in a way that is educational and respectful. “For us, the existence of the gallery and the collection inspire us to be constantly looking at Indian art and constantly inviting Indian artists into this community,” she says. Also, they haven’t shied away from acknowledging the darker sides of the project. “I’d say that yes, fighting racism is one of our goals in this effort. Indian people are often somewhat invisible in our white culture, so part of MAM’s role is to create some visibility.”

Inviting artists not only to display their work but to talk about it as well has allowed audiences a chance to gain greater insight. “We bring in Indian artists as often as we can to help us with interpretation, to do programming, to find deeper meaning and layers of commentary in their work, and to enter into a dialogue with the audience,” says Millin.

In an effort to take this mission of dialogue and interpretation further, MAM commissioned work from various Indian artists to be part of a portfolio entitledNative Perspectives on the Trail. In it, 15 artists offer their own response, from a Native perspective, to the journey of Lewis and Clark. The result is a collection that is at times poignant, angry, delicate and even humorous. This portfolio has been printed in a booklet, and the exhibit itself traveled to galleries and schools throughout Montana, expanding its reach beyond the museum and offering a new perspective on a familiar story. Clairmont, whose work is included in the portfolio, says “that project is an excellent example of the kind of cooperative venture that happens between Indian artists and MAM’s staff.”

As the collection becomes better known and exhibits draw crowds during First Friday art walks and museum events, the staff has seen the community open up to American Indian art. Hughes recalls a recent event, during which “we saw a lot of college students gathering around George Longfish’s pieces. They really love the pop-art quality, and relate to the commentary he’s making about society.”

And this makes Glueckert, and the rest of the staff at MAM, glad. In their own way, they are helping create culture. “There’s no recipe,” Gluckert says, “for culture. It’s constantly growing, changing and becoming.” While the Contemporary American Indian Art collection allows artists a fabulous venue in which to show their work, it does something else equally important: It allows audiences to contemplate and connect to ideas, beliefs, and imagery that they perhaps otherwise never would encounter. “What this is,” Glueckert says, gesturing to the art around us, “is a community growing.”

- “Indian Country Passage Denied” | Collagraph | Corwin Clairmont, 2005 | Photo courtesy of the Missoula Art Museum

- “Modern Times” | Lithograph | Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, 1993 | Photo courtesy of the Missoula Art Museum

No Comments