23 Jul Outside: Secret Waters

Last summer, as gas rose to $4 a gallon, I decided that a footloose angling life was something I couldn’t sustain. I vowed to stay close to home and fish local waters, with a focus on the lakes and reservoirs I’ve overlooked during my seven-year stint in Ennis, Mont.

I’ve never understood why most fly fishers, in our thirst for moving water, ignore lakes in such a decisive way, especially in the Rockies where progressive management and perfect growing conditions allow anglers to take some of the biggest trout on the planet. There’s no denying that all fishermen, no matter their gear preference or which specie they pursue, would prefer to catch large fish rather than dinks. That only emphasizes the question: Do you want to stand in a river for days on end hoping for a miracle 25-incher, or would you rather head to a profitable lake and, perhaps, land a succession of 5-pounders?

Lakes offer other attributes, too. In fact, some of my appeal for lakes dates back to youth when I joined family in the lowlands of western Washington and trolled pop-gear and a worm (massive 3-inch-long bladed contraptions) for trout that measured no greater than 12 inches. Fighting those fish on pop gear amounted to reeling in a 10-inch pinner drowned on the end of a line. Still, I remember those days with affinity and I think I know why. On a raging river, conversation between anglers is limited; on a lake, as long as the wind isn’t howling, anglers carry on conversation even when separated by significant distance.

Of course, that serenity has pitfalls. I learned that the hard way, years ago, when a college friend and I cruised past a beach full of sunbathing beauties with an old 15-horse outboard chugging along. My friend made his pick and described which particular romance she might be missing in life. When we cut the engine and stopped laughing there wasn’t a sound on earth. My friend whispered, “Oh no.” One of the girls rose, pointed a finger at my friend and said, “You pervert. Get out of here!” Uh, so you’re not joining us around the campfire tonight?

Last July I phoned a friend, Dan Summerfield, and asked if he had time to fish. He used to be my go-to guy when I needed a fishing partner, but now he’s an engineer in Bozeman and if you’ve seen Bozeman lately, you’d know why he’s been so busy. This time he said, “Yea, I have plenty of time.” He pushed for a float on the Madison, but I told him it’s lakes or nothing, man.

We met early the following morning and left Ennis in the dark, our grill pointed toward a chain of lakes I’d learned about several years prior when I interviewed a local biologist. I asked if there was something anglers were overlooking in their thirst to fish the Madison and other regional rivers? He said if people really want to catch large fish they needed to focus on southwest Montana’s lakes. “You aren’t going to catch any really big fish on the Madison or anywhere else unless you fish the deepest pools with sinking lines and whitefish imitations.” He added, “There aren’t many guys willing to do that when 15-inch trout are rising to PMDs and green drakes around each bend.”

Nor are many anglers willing to spend time learning how to fish lakes, which appear as giant, flat-surfaced puzzles. No exposed rocks. No soft current next to the bank. No choppy runs dropping into defined pools. Compared to a river, anglers find lakes perplexing at best.

Anglers who do spend time studying lakes, however, find defined features, such as submerged weedbeds, partially sunken or fully submerged logs, rocky points and drop-off ledges, fertile flats and sheltered bays — all excellent places to find fish feeding at the surface or all depths below. In addition, lakes provide awesome insect hatches and when the trout get on a particular bug they lock in just as aggressively and selectively as river trout. During summer and early fall anglers may find a variety of quality bugs on the water including damselflies, midges, water boatmen, Tricos, PMDs and Callibaetis.

Callibaetis mayflies, in particular, are a summer staple for trout and they are abundant on most stillwaters between mid-June and the end of August. They’re a big bug, matched early in the season by size-14 and 16 Parachute Adams’ and Callibaetis Cripples. Later, meaning late-July and August, those insects — the brood from early season Callibaetis — are smaller and matched by size-16, 18 and 20 patterns. On productive Callibaetis lakes, the emergences and spinnerfalls are immense. Typically the hatch begins in the morning, builds into early afternoon and then tails off by 3 or 4. During a heavy emergence, those bugs, plus scads of spinners which also fall in the afternoon, can cover an angler’s hat. Breathing through the mouth takes on a sporting quality.

That’s what Summerfield and I found when we arrived at a lake the biologist suggested. It sits above 5,000 feet but I wouldn’t call it a high mountain lake. Instead, it stretches out on a plateau surrounded, mostly, by rolling timbered hills. A rough, heavily rutted road ran to a parking lot. From there we dragged our Watermasters about a half-mile to the water.

Summerfield is the kind of guy who could spend 15 minutes at a gas station in Island Park, examining his check record while across the road on the Henry’s Fork big trout scarfed down green drakes at a frantic pace. While he played with his oars, and built a new leader, and organized his flies, and double knotted his laces, and put on another layer of sunscreen, and trimmed his nose hairs, I performed a few quick oarstrokes, played out some line and then grabbed the rod when a fish snapped at a Hare’s-Ear Nymph trailing 20 feet behind. Before Summerfield took one oar stroke I’d landed and released three rainbows ranging between 14 and 16 inches.

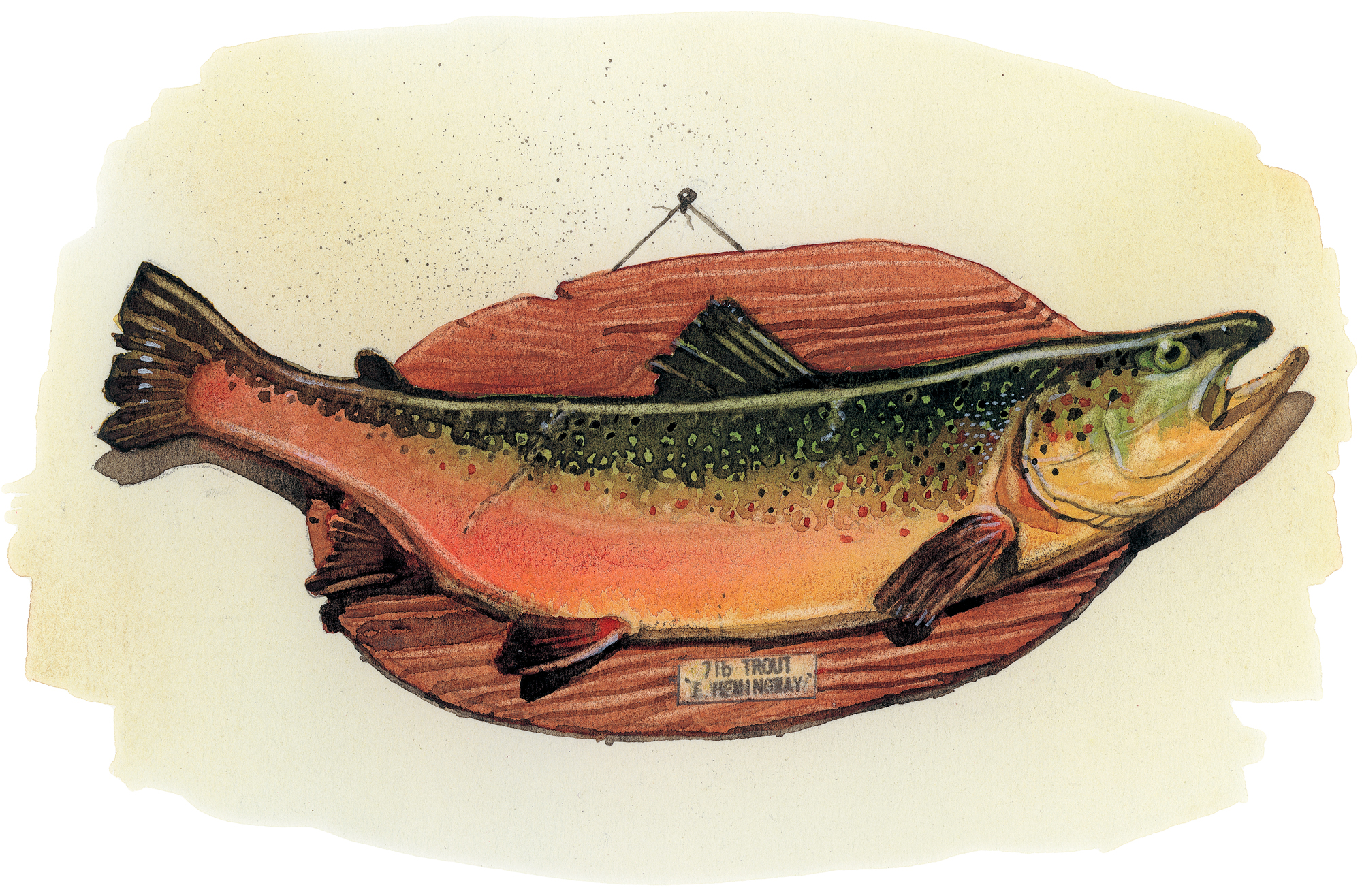

We’d stopped at a lodge on the drive in and examined a couple oversized mounts behind the bar. One was a big brown trout, which must have weighed 10 pounds or more when the fish was alive. Another was a rainbow that may have weighed 8 pounds. Nobody knew exactly where the brown came from, but the rainbow was local, taken where we planned to fish. When I asked if there were still some wallhangers around, the proprietor scrunched his nose, leaned in close and hissed, “A lot of people come back saying they hooked fish they couldn’t land, but we don’t know whether to believe them or not. You know what I mean? If many people knew the answer to that question we’d be overrun with anglers and the experience wouldn’t be very good anymore, would it? I like it the way it is; we see a few fishermen, they catch some good fish, and the lodge stays in business.”

Then, like a kick to the groin he added, “You’re not a writer or a TV guy are you?”

Oh, sort of.

By 10 a.m. there were lots of Callibaetis on the water and more frequent rises. I stuck with a Hares-Ear and fished under the surface around submerged weedbeds while Summerfield went with a dry fly. After Summerfield landed a couple good trout, including one that went an honest 18 inches, he said, “Thomas, this is the way to go. Quit cheating. You’ve got to put on a dry fly.”

I’d caught six fish in the time it took Summerfield to land two and each cast drew a tug. To take Summerfield’s advice, I felt, would have been like handing the ball back to the ref and saying, “You made the wrong call. I traveled.” In other words I, too, prefer catching fish on dry flies but, all things equal, I doubt the fish care whether they were taken on a sunken foam-body beetle or a Thorax Callibaetis tied with the most select Whiting hackle. In fishing, the adage, “If it aint broke, don’t fix it,” rings true with me.

Then, shortly after I’d snubbed Summerfield’s suggestion, I watched his cast land near shore, next to a fully shaded and partially submerged log. His fly, a Parachute Adams, settled momentarily. When Summerfield gave it a twitch, as if it were drying wings and preparing for flight, a form darted from under that log and moments later an elongated snout parted the water and took the fly down. A tall dorsal, a long back and a sail-like tail followed in the most placid of motions. There was a brief moment, like the time it takes a child to scream after they’ve smashed fingers in a door, before the fish realized it was hooked. Then, the fish made a quick burst, snapped its head on the surface, like a great white shark killing a sea lion, and Dan’s line flew back at him. I don’t think his mother would have approved of the response.

By mid-afternoon the Callibaetis were out of control. They crawled in our ears, marched in unison along our boats, and crawled into every beverage we opened. I took a bite of sandwich and ingested a brace of Callibaetis in the process. I was switching to a dry fly and Summerfield was setting into another good fish when a shadow covered the lake. I looked up and saw the charcoal sky behind. Suddenly it was super quiet, sticky hot, and there was a flash in the sky. Before the storm set in at full force, Summerfield and I were off the water, dragging boats uphill to the truck.

Between us we may have landed three dozen fish that day and we’d seen — get this — one other angler, a guy who made a half-hearted effort from shore. Summerfield may have lost a 10-pound rainbow and I’d cast to a couple in the 5-pound range.

We spent at least an hour in the rig watching the rain and hail bounce off the hood. While T-Hip played on the stereo Dan and I talked about steelhead and where we might join to fish them that fall.

“I’d hit the Clearwater but it is wall-to-wall anglers in October,” I said. “The Deschutes, too. You have to be on the water, patrolling a run before first light. Otherwise you’re too late and second over the water. Steelhead don’t like anglers who are second over the water. Ditto on the Ronde.”

“Maybe we should forget the steelhead and try the Yellowstone for browns,” Summerfield suggested. “Or maybe we could go into Yellowstone and hit the Barnes Pool with streamers. Or maybe we should hit the channels near Ennis. Or how about the Missouri or Rock Creek or Slough Creek, the Lamar and the Firehole?” After a pause, Summerfield shook his head and said, “Those places are super crowded, too.” Then he added, “You know, this lake fishing deal isn’t so bad. Some of these fish are as big as steelhead. Maybe we should come back here.”

As the rain subsided we considered hiking into a lake where the fish are reported to be giants, but we’d already landed more big trout in a single day than we would catch during an entire season on one of those local rivers. Besides, the last time I’d visited that lake I saw a man wading to his knees wearing nothing more than a pair of boots and some bone-white, spandex-tight Fruit of the Looms.

I’d cashed my stimulus check a day earlier so on the way home Summerfield and I stopped at the lodge on Bush’s spend, spend, spend direction. We waltzed in and ordered two burgers, two Rainiers and two shots. The proprietor said, “So you had a good day. Now what do you say to people?”

I fired down a shot and said, “It was alright. We saw a ton of Callibaetis, caught a few nice fish and didn’t see another soul. And we may have hooked one we couldn’t land. That’s it.”

The proprietor grinned, nodded, poured three more, then raised his ounce, and said, “Glad you guys like this lake fishing deal. When are you coming back?”

No Comments