15 Jul Artist of the West: Pop Culture Meets Modernism

COMING FROM EUROPE AFTER THE devastation of World War II, Willem Volkersz brought with him a rich history that is reflected in everything he does. Volkersz’s work combines the quintessential American Dream with an outsider’s perception of attainment. By using neon and kitschy found objects picked up at junk shops and second-hand stores Volkersz at once embraces our popular culture and forces a filter on Modernism.

His most recent series is based on the Montessori school he attended in Amsterdam — a school he would later learn lost almost 200 children to the Nazi death camps.

“In 2006 I was contacted by a teacher of mine from Amsterdam,” Volkersz says. “From her I learned that 166 children from my school died during the Holocaust.”

In 1941 the Nazis built a separate school for Jewish children and at that point they transferred out of Volkersz’s Montessori school. From there they were sent off to concentration camps in Auschwitz, Bergen-Belsen and Sobidor in Poland. By 1943 those schools were closed and Jewish children were sent straight to the camps.

“It was hard to believe that so many children from one school were taken,” Volkersz says. “But thinking back, a lot of refugees were drawn to that part of the city.”

Volkersz began a series of pieces entitled In Memoriam that has been traveling around the area. Surrounded by 166 wooden suitcases with the name, age, date and place of death of each student from the Montessori school, a solitary neon figure of a stooped boy carrying a suitcase in primary colors stands three-suitcases high — a ghost, a small soul, forever a transient in this world.

The suitcases started as a metaphor for travel, but the more he thought about them, the suitcases became a metaphor for one’s journey through life.

“At one point I realized I could hide the electrodes and transformers for the neon pieces inside the suitcases as well,” Volkersz says. “So the suitcases became utilitarian as well as symbolic.”

The wood used for the 166 suitcases in In Memoriam is recycled, picked up from the trash of a furniture store where Volkersz’s son worked — which gives the suitcases a feeling and look of having been used. It is also based on the fact that those who were rounded up and sent to the camps were allowed to bring a single suitcase of their personal belongings.

Seeing all those cases, nearly identical, evokes a strong visceral reaction. Even though these atrocities happened 60 years ago, it still resonates.

“Each show is a bit different because I get volunteers to carry in and place the suitcases in the space,” Volkersz says. “At the Bozeman High School exhibit the students read each name as they placed the suitcases down. At one point a girl read the names on two of the cases she was carrying. They were the same age and had the same last names but they died in two different places.”

Twins, separated and sent to different death camps.

“That look on her face was more than anything I could say,” Volkersz says.

Ellen Ornitz, curator of the Jessie Wilber Gallery at the Emerson Center for Arts and Culture in Bozeman, will show Volkersz’s work in the early spring of next year.

“It will be our school outreach show — with our target audience being high school students, MSU students and faculty,” Ornitz says. “When I first saw the work I was drawn in by the symbolism, and how it’s so accessible to the public.”

In particular the topic of the Holocaust.

“For kids growing up today, World War II is very historic for them,” Ornitz says. “As the older generation is getting up there, I feel there’s a real need for education. One of Willem’s greatest attributes is being an exemplary educator. As an educator and an artist he wants to communicate what the war was about. He makes it personal. It’s not at all like reading history books.”

There are six or seven pieces in the Holocaust series, but in the end the work was so emotionally exhausting that Volkersz recently moved away from it for a while concentrating on his Paint by Numbers series.

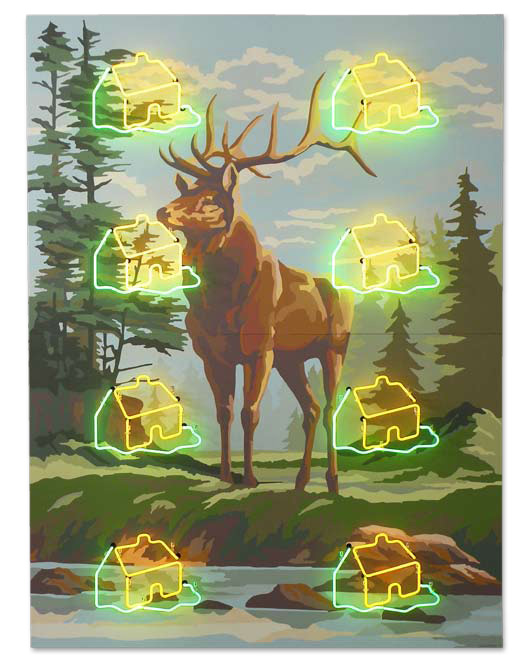

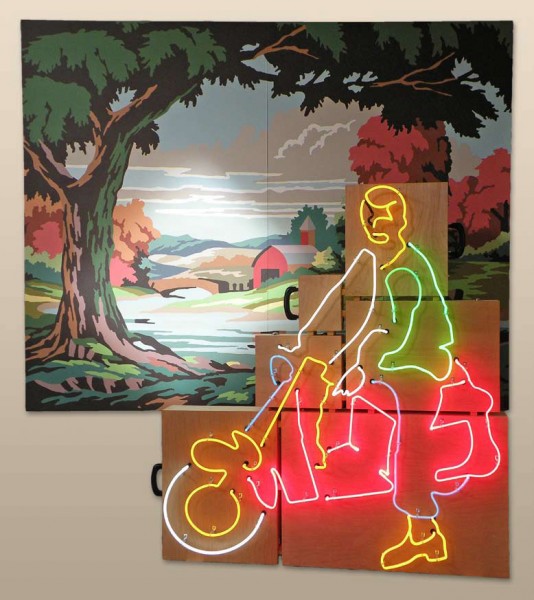

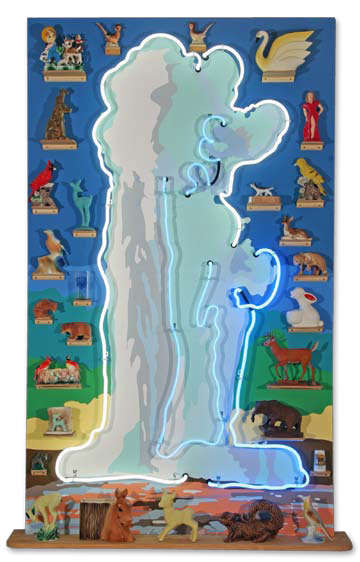

“Willem is basically playful and optimistic,” Ornitz says. “He loves folk art and pop culture. As a curator, I find his use of materials unique; I don’t know of anyone else around here who uses paint by numbers for a springboard combined with neon and found objects. More importantly to me is his commentary, combined with found objects and with things he makes himself — there’s something very contemporary about the process.”

Small children’s chairs hang from an overhead beam — green, red, yellow — as if Volkersz is giving a lecture on flying in his studio. Postcards tacked to the walls under the rows of small windows and the few shelves house dozens of the kitschy porcelain statuettes he’s collected from junk stores and second-hand shops. On the far wall, a high shelf holds a dozen or more globes — which adds to the feeling of a classroom — in all shapes and sizes, the blue of the vast oceans stand out clearly from across the space. In a corner, suspended from pegs, are pieces of neon from projects past.

The pieces he’s still working on is based upon four old paint by number paintings he came across in the shops. Combined, they form the idealized landscape of America: the mountains and fly fishing of the West, the farmland of the Midwest, a pink flamingo covering the Southeast and a Maine-like lighthouse forming the Northeast, fitted into an outline of the United States. The piece is made of two quarter-inch birch panels that make up a 35- by 72-inch piece called Invasive Species. Along the completely black background, Volkersz included shelves that hold various found objects of ceramic birds, including a neon parrot with a martini glass.

Coming to America and settling in Seattle during the early 1950s, Volkersz sees the country through the eyes of a perpetual immigrant — the American Dream in all its various incarnations.

“I was 14 when we came here and when I was 16 I took a road trip and documented the roadside environment — people’s yards, whirligigs, billboards and neon signs,” he says. “When I went to art school I started to work with those photographs and I realized my fascination with pop culture.”

Part of that era was the iconic look of paint by number sets sold at dime stores and arts and crafts shops.

“They have very defined shapes and no gradations of colors,” Volkersz says. “To me it’s a kind of celebration of popular culture. I’m also looking back on an America that was simpler than it is now, with a sense of security and safety and promise.”

Doug Turman, of the Turman Larison Contemporary gallery in Helena, represents Volkersz’s work and exhibited In Memoriam last winter.

“From the gallery point of view it was a chance to do something that wasn’t commercial,” Turman says. “It was such a beautiful piece in its construction and its idea that for us it was a high point. We were a very good museum for a month. It was fun to offer a space that was very different for him.”

Volkersz usually does exhibit his work in museum settings, especially some of his bigger pieces.

“Our backspace was much more intimate,” Turman says. “It was art for art sake, so to speak.”

In Volkersz’s neon and found object pieces, he brings another subject to the table. By combining the symbols of postwar America with a style of art that assumes anyone can make a painting, Volkersz is in fact commenting on our present-day world.

“As a painter, I appreciate how well the neon, paint by numbers and the kitsch objects could so easily become cliché,” Turman says. “Other artists might use that to cover up their weaknesses. Willem’s work is strong all the way across. He uses the neon very judiciously. If he’s making a reference to kitsch, it’s done very tastefully. Never for a quick, pleasing ‘notice me’ kind of attack. You see a lot of gimmick in art but that’s not his work at all. The quality of his neon and his painting is very high. Even his using these easy to grab images — especially since he makes up a lot of those paint by numbers images — is more sophisticated than it may at first appear.”

Because there is a simplicity to the images he uses, Volkersz runs the risk of appearing simplistic.

“But he has a worldliness to his work,” Turman says. “He has a sensibility that is broad. His work is quite ambitious — considering the construction, complexity and the size. His work is challenging, in that it’s complex, different ideas and mediums. There aren’t that many artists of that persuasion around.”

- “Home on the Range” | Neon, Wood, Paint | 95 x 72 x 6 inches

No Comments