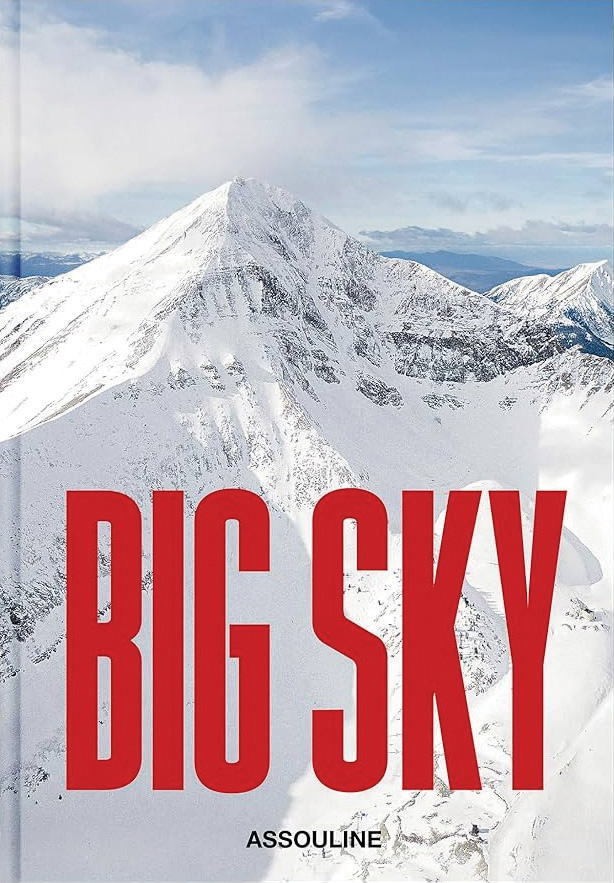

21 Nov Round Up: Between the Pages: An Excerpt from Barbara Rowley’s Big Sky: Montana

Editor’s Note: Barbara Rowley, writer and longtime resident of Big Sky, Montana, explores the story of a place deeply rooted in outdoor splendor in her 2024 title, Big Sky: Montana (Assouline). The book delves into the history of Big Sky Resort, revealing how the ski area has redefined the American ski experience and shining a spotlight on the destination’s continued allure. This excerpt is published with permission from the author and publisher.

In 1968, after 14 years building a national following as one of the anchors of the nightly NBC newscast that bore his name, Chet Huntley had a big idea.

The son of a railroad man who grew up in modest circumstances, Huntley wanted to create economic development for the state and people he loved. He would retire to create a world-class ski and summer resort in a place few would expect — his home state of Montana. He had the location — a valley he knew where he loved to fish and ride horses — and he expected others would want to visit as well.

In retrospect, the audaciousness of this idea would be difficult to overstate.

Yes, there was snow and terrain. But skiers? Not so many. There weren’t even many people. At the time, neither Montana (the fourth biggest state in land size in the U.S.) nor any of its immediate neighbors, had populations that even came close to a million. The location — the broad valley extending from the base of Lone Mountain to the Gallatin River — was gloriously beautiful, and almost completely without infrastructure.

There was no there, here: no sewer or city water, no post office or fire department, no paved roads, and no roads at all past the B-K, today known as the Lone Mountain Ranch. A single power line meant the few electrified buildings around were regularly plunged into darkness, and telephone service was limited to a party line shared by eight people. Notes from the resort’s first general manager, Gus Raaum, indicate that when the planned mountain village needed phone service, “they hired a helicopter to roll out the telephone line … about 10 miles, on top of the trees.” Hungry rodents kept cutting the line, remembers Raaum.

As for Huntley himself, he was a career broadcaster in radio and television with a deep and measured voice who had shepherded the American public through assassinations, protests, a war, and multiple political scandals. While a lifelong outdoorsman, he was not an avid downhill skier and had no history in development, so even conceiving of Big Sky marked him as a visionary, especially because what he envisioned had so little precedent.

Huntley wouldn’t be following the model of Telluride or Aspen, co-opting the infrastructure of an old mining town and simply adding ski lifts and hotels. And he couldn’t remake Jackson, which, as a Yellowstone Park gateway town, already had hotels, restaurants, a city government, and workers eager for year-round employment. Not even Vail — another from-the-ground-up ski resort started seven years earlier — offered a truly comparative model. Vail had a highway, the nearby town of Eagle — and the city of Denver, population one million in 1968, was just two hours away. Denver had a major airport; Bozeman had just one daily direct flight — and it was from Billings.

No Comments