25 Sep Excursion: Montana’s Inland Sea

When I was stationed as a medical officer on the Fort Peck Reservation 50 years ago, I fell in love with the prairie but missed trout fishing. I found a few farm ponds with stocked rainbows, but that didn’t satisfy my need for dry flies and a clear current. One weekend, I decided to drive all the way to the Madison River, where I frequently enjoyed fishing as a kid.

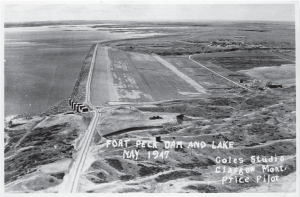

By then, I had heard about the Fort Peck Dam but had never seen it. Since my route took me by the dam, I was eager to take a look. When I arrived at the spot where the map said it was supposed to be, I couldn’t spot it. As I finally figured out, that was because my truck was sitting on top of the dam, which was so immense I didn’t recognize it for what it was. As a kid growing up in the West, I’d seen many dams but nothing on this scale.

The dam’s spillways control the water level throughout the Lower Missouri. Photo by CHUCK HANEY

The body of water stretching westward looked equally impressive, with a convoluted shoreline that reminded me of the North Pacific, where I had grown up. However, in contrast to the coniferous rainforest bordering the sea, the lake’s shoreline was barren save for sagebrush and grass. The dissonance between that huge body of water and the dry prairie surrounding it felt surreal.

Even though I didn’t know anything about fishing the lake, I knew I needed to explore it and learn.

Now, for some facts and figures to objectify my overwhelmed response to my first view of the lake. Fort Peck is the fifth-largest reservoir in the country, with a surface area of 245,000 acres. The length of its shoreline is staggering. After the dam’s completion in 1940, water began to seek its own level in the myriad coulees that define the Missouri River Breaks. Although it fluctuates with the water level, its mean length is 1,520 miles — over 200 miles longer than the entire Pacific Coast in the lower 48 states.

The lake is surrounded by spectacular uncrowded scenery on the Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge. Photo by CHUCK HANEY

Construction of the dam was a remarkable engineering feat. It began in 1933 as a Depression-era Public Works Administration project. In addition to generating hydroelectric power, it was designed to prevent downstream flooding in the fertile farmland along the Lower Missouri River. The dam was also meant to allow better control of water levels for barge traffic in the Lower Missouri– Mississippi drainage. The Roosevelt administration sought to create jobs for the legions of unemployed workers the Great Depression had created. At the peak of construction activity in 1936, the Army Corps of Engineers employed 10,000 workers at the dam site. Along with their families and the infrastructure needed to sustain them, the sleepy little town of Fort Peck became one of the largest cities in eastern Montana at the time.

Engineers used a novel combination of dredging and hydraulics in the dam’s construction. Upon completion, it became one of the world’s largest earthen dams. This accomplishment was not without tragedy. In 1938, part of the dam began to fail, miring several dozen workers in hydraulic muck. Eight died, but only two bodies were recovered. The other six remain buried in the dam’s core, perhaps as a reminder of human fallibility during confrontations with nature.

A year after the dam’s construction began, the remote area’s population had already begun to swell with workers. | ARCHIVES AND SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, MANSFIELD LIBRARY, UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA

Dam construction inevitably leads to controversy between development interests and preservationists. President Franklin Roosevelt expressed a vision of Manifest Destiny when he visited the dam in 1934 and described “… the Fort Peck Dam as the fulfillment of a dream … only a small percentage of the whole dream covering all the important watersheds of the nation.” I can think of no better rebuttal than Thomas McGuane’s accusation that, “We have used our rivers the way a junkie uses his veins.”

A confession: I cannot look at any body of water without considering its angling potential. Both figuratively and literally, Fort Peck Lake lies hundreds of miles from Montana’s world-famous trout streams but still offers some of the best angling opportunities in the state.

The lake’s convoluted shoreline is longer than the entire Pacific Coast along the Lower 48 and provides vast and varied fish habitat. | CHUCK HANEY

Forty-seven species of fish inhabit the reservoir, evenly divided between native and introduced species. That number includes a variety of suckers, minnows, and so on that are often dismissed as “trash fish” (I dislike the term) because of their limited recreational angling value. The list also includes a number of widely admired gamefish: coho and chinook salmon, sauger, walleye, saugeye (a hybrid cross between sauger and walleye), northern pike, smallmouth bass, and channel catfish. Only the sauger and channel cat are native to that stretch of the Missouri drainage. Before dismissing the rest as alien invasive species, we should remember that our beloved rainbows and brown trout were also artificially introduced.

As this 1947 aerial photo shows, the dam is so long and large you may not recognize it as a dam as you drive across the stretch on Highway 24. | ARCHIVES AND SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, MANSFIELD LIBRARY, UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA

The lake is also home to the only surviving population of paddlefish, a unique prehistoric family of ray-finned fish with a cartilaginous notochord instead of a bony spine. Reaching weights over a hundred pounds, their exaggerated rostra (the “paddles”) make them look like something from a sci-fi movie. Their roe produces highly regarded caviar. Despite their size, they are of limited angling value since they do not take conventional lures or bait. However, anglers have learned to snag them when they run upstream to spawn, creating a unique local fishery during the spring.

The size of the lake’s gamefish reflects the size of the lake. Nine state records have been set at Fort Peck, more than at any other body of water in Montana. In addition to several species in the trash-fish category, that list includes respected gamefish such as chinook and coho salmon, sauger, channel catfish, and smallmouth bass.

Yes, you can catch warm-water fish on flies! This Fort Peck walleye hit a black leech imitation. | DON AND LORI THOMAS

Fishing the lake is a lot like fishing the ocean, with fish concentrated in a few select locations surrounded by a whole lot of water. Learning the lake and its secrets requires lots of experience, admittedly more than I have myself. In addition to the appeal of the variety it offers, the lake’s size and the complexity of its shoreline provide plenty of opportunity for anglers to disperse and fish in solitude. Fifty boats on the Madison makes a crowd, but not so on Fort Peck Lake.

The fish that put Fort Peck on the map as a premier angling destination was the walleye. Introduced in 1951, their size made the lake famous, with specimens weighing more than 17 pounds.

As a former Alaska resident and commercial fisherman, I have trouble wrapping my head around salmon that have never seen saltwater, but chinook salmon, introduced in 1983, now provide a popular fishery. Because the lake lacks suitable spawning habitat, all of its salmon come from a rearing facility downstream from the dam. Lake trout, introduced in 1953, provide another deep-water opportunity to catch large, tasty fish.

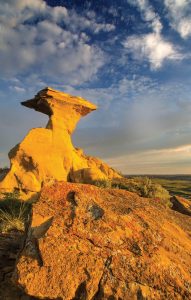

The Missouri Breaks contain striking limestone rock formations. Meriwether Lewis and William Clark commented upon them during their upstream journey in 1805. | CHUCK HANEY

All of these gamefish benefited greatly from the 1984 introduction of cisco, a foot-long silvery forage fish that is actually a member of the salmonid family. The cisco thrived and now provides the base of the lake’s food chain for most gamefish. Their abundance is credited for the sharp rise in both the numbers and size of the lake’s angling quarry.

Certainly, though, there is more to the Fort Peck ecosystem than its angling opportunities. Almost all of the shoreline lies within the Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge (CMR), the second-largest national wildlife refuge in the contiguous 48 states. In addition to spectacular scenery in the Missouri River Breaks, the CMR offers over a million acres of public land for hiking, seasonal hunting, camping, and wildlife photography. For maps and information, contact the CMR headquarters in Lewistown or visit fws.gov/refuge/charles-m-russell.

Its heyday over, the town of Fort Peck, just north of the dam, is now a sleepy prairie outpost with 250 residents. Basic services are available, and I’ve enjoyed a number of overnight stays there after growing tired of sleeping on the ground. Remarkably, it hosts an excellent summer theater every year that’s well worth the visit (fortpecktheater.org). No kidding.

The vast, fascinating prairie terrain surrounding the lake offers endless opportunities to camp and explore. | CHUCK HANEY

Another local highlight is the under-visited Fort Peck Interpretive Center at the south end of the dam. Operated jointly by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, this small yet elegant facility offers a wealth of history and vintage photographs of the dam’s construction. Even better from my perspective, it includes a wonderful display of the area’s wildlife dating all the way back to the Cretaceous Period, including a nearly complete Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton found nearby. Aquariums hold specimens of the lake’s fish, both native and introduced. Because the center is open on an irregular schedule, visitors should call (406) 526-3493 ahead of time or visit fws.gov/refuge/charles-m-russell/fort-peck-interpretive-center.

Not long after I moved to the remote northeastern corner of Montana 50 years ago, I recognized the disconnect between the prairie and the western half of the state. The glamor lay hundreds of miles away, as did our growing reputation as a world-class trout fishery. (This was long before Brad Pitt and The Movie spoiled the secret.) People wanted to go to the mountains, not the allegedly barren plains. One reason I was assigned to the Fort Peck Reservation was that no one else wanted to go there.

Within a month of my arrival, I started to feel like Brer Rabbit in the briar patch. Anything but barren, the prairie surrounding Fort Peck Lake is rich in wildlife, and the Missouri Breaks are breathtaking. The sluggish waters nearby are rich in warm-water fish, which I taught myself to catch on flies. During the time I spent there, I never saw another fly-rod angler on the water or bird hunter in the field.

The contrast between the vast lake and the arid terrain that surrounds it is striking, offering the best of both worlds. | ROBERT APPLEBY

Fort Peck lies a long way from anywhere by conventional standards, which may be one of its saving graces. Since Margaret Bourke White’s famous black-and-white photo of the dam graced the cover of Life magazine’s first issue and the area provided the setting for two of Montana writer Ivan Doig’s novels, Fort Peck hasn’t received much national attention. The uncluttered prairie ambience and the iconic Big Sky that stretches horizon to horizon overhead remain largely unchanged today.

Fort Peck Lake and the dam that created it offer a fascinating slice of Montana history, and the local wildlife and scenery can compete with anything farther west. If you go, don’t forget to bring your rod and reel.

A central Montana resident since 1973, E. Donnall Thomas Jr. has been everything from a physician to a bear hunting guide in Alaska. He writes about the outdoors for numerous publications and lives in Lewistown, Montana with his wife, Lori, and their bird dogs.

No Comments