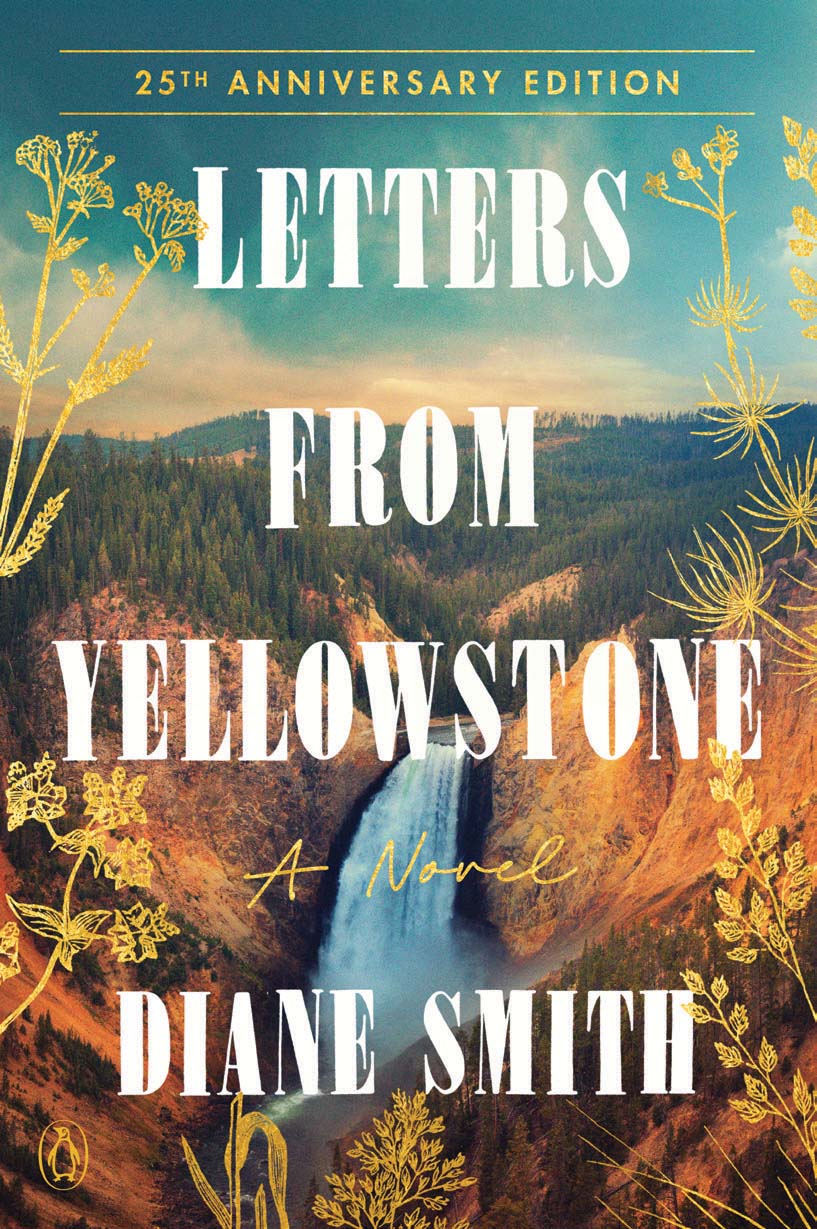

22 Nov ROUND UP: BETWEEN THE PAGES: AN EXCERPT FROM THE 25TH ANNIVERSARY EDITION OF LETTERS FROM YELLOWSTONE

Editor’s Note: In 2024, award-winning novelist Diane Smith celebrated the 25th anniversary of her first book, Letters from Yellowstone, with a special edition of the title. The book, creatively composed in letter format, documents a fictionalized botanical field study in Yellowstone National Park in the late 1890s following A.E. (Alexandria) Bartram, a spirited young woman who was inadvertently invited along. It won the Pacific Northwest Booksellers Association Fiction Prize and was a One Book Montana statewide read. This excerpt, featuring a letter from A.E., is published with permission from the author and publisher.

Alexandria Bartram

National Hotel

Mammoth Hot Springs

Yellowstone National Park

May 21, 1898

My dearest family,

I write to you, believe it or not, from Yellowstone National Park. Mother, one sight of this place and you would understand why I had to experience it for myself. It is as though I have traveled back in time, to the very edge of the universe, where the earth, still in its most primordial stage, sputters and bubbles and spews out the very origins of life.

That is not to imply that the modern-day world has forsaken Yellowstone National Park. On the contrary. It is like a small city here, complete with post office, hospital, laundry, riding stables, barber, and a large barracks facility for the U.S. Cavalry, which administers and patrols the Park.

The hotel where I am staying is a large, very modern tourist facility, conveniently located within walking distance from the boiling cauldron further up the road. There is a spacious lobby, dining room, even a ballroom, and hot and cold running water on every floor. My fellow lodgers, many of whom are women you will be relieved to know, entertain me over dinner with stories of their travels abroad or their mishaps in the Park. These women appear to be an adventurous lot, arriving before the six-day coupon tours commence, often traveling on their own or in small groups of like-minded souls, demanding equal time in the hot ponds, which are otherwise monopolized by the men.

When I tire of my dinner companions and their tales, I can retreat to the lobby with a cup of tea or a glass of English sherry and enjoy a good book (right now, I am reading a history of the Park written by the resident historian, another regular in the dining room). While sitting thus by the fire, a young pianist, knowing of my love of Schubert, selects his lobby repertoire as if to entertain me alone. I feel as though I have been transported to the wilds of New York City — not the wildest West.

If I long to view the Park’s wildlife I have heard so much about, I simply step outside onto the verandah and there I am joined by more wildlife than I know what to do with. Just last night, for example, 19 elk (Cervus elaphus) lingered on the cavalry’s snow-covered parade grounds just outside the hotel, their moist, warm breath mingling with the steam from the hot springs behind them. It was a lovely sight until I realized that these handsome and stately creatures have been reduced by habit and convenience to begging for handouts, a degradation encouraged by the hotel staff, which throws out table scraps after dinner.

The Park’s other persistent and virulent form of wildlife (a subspecies I have Linnaeanized Homosapiens horribilis, but who are identified locally by their common names of Whiskey Jack, Lord Byron, Geyser Joe, Handful of Dollars, etc.) can also be viewed after dinner, congregating in or around the hot baths up the hill from the hotel, or in the hotel itself, caging drinks and entertaining guests with their tall tales. One claims to have fallen into Old Faithful only to be spit back out at Beehive Geyser miles away! Another told of how the birds in Mammoth drink so much hot water, they lay hard-boiled eggs.

“You watch for ’em, next time you’re out there, little lady,” one told me. “Hard as rocks, those eggs are. Hard as rocks.”

Not to be outdone, a third leaned over to a particularly gullible-looking young woman sitting next to me and warned her quite sincerely of the dangers of wading in Alum Creek.

“Why, it’s so potent,” he cautioned, “it turned my first set of horses into Shetland ponies, just by settin’ foot in it,” he said.

At this point, the young woman’s mother intervened, suggesting that if the creek were as powerful as he suggested, then the teller of the tale would no doubt benefit from soaking his head therein. Great laughter erupted amongst the group, but the storyteller had the last laugh when a large jar of beer appeared at his table not long after the mother and daughter returned to their rooms.

This natural ability to entertain and successfully beg, borrow, and steal from tourists must be yet another form of specialized western selection and adaptation, not unlike that demonstrated by the Park bears (Ursus americanus, U. cinnamomeus, and U. horribilis if you can imagine!), which have learned to rummage through the garbage dumped behind the hotel for their benefit — or, more likely, for the benefit of the hotel’s guests. They have even learned to beg at the kitchen pantry door (I am referring now to Ursus americanus, not Homosapiens touristii americanus!) and take apples and other treats directly from the hands of fools (for only fools would be so foolhardy!).

Thoreau was right. We are at risk of civilizing our native species right off the face of the earth. We must all work to document this last wild place in America before it, too, is gone from us forever. If the fauna is so easily domesticated, can the flora be far behind? …

No Comments