25 Sep The Cowboy and The Immigrant

When my feet sunk deep into the wet ground far away from the hills where I was born, I knew my husband and I had found the right spot. Our horses had steadily climbed the steep mountain trail for 12 miles, weaving through sheer cliffs. Here, on top of the pass, the rock gently leveled out on a marshy 40-acre meadow — the perfect campsite at 6,700 feet.

For 50 years, one of the last living (and working) legends of the American West, Arnold “Smoke” Elser, made camp here. Now at age 90, Smoke is well-known beyond Montana as an award-winning outfitter, horse and mule packer, teacher, and conservationist. Our unlikely friendship brought me to the top of this mountain, changed my life, and gave the world his stories.

Wildfire smoke clogged my nose and tainted the otherwise sweeping view of his summer home, the Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex: 1.5 million acres of wild mountains, rivers, and animals preserved in perpetuity in part because Smoke has committed to protecting the rugged, roadless area since he saw it for the first time. It was an unusually warm fall day, but tucked away on the hill, a small spring still subirrigated a fresh supply of spongy grass, providing a snack for our sweaty horses.

Close by, Smoke once found a lost hunter who was haunted by a mountain lion on a rainy night. On a different occasion, 15 feet high in a tree now burned, he’d waited for hours, napping while the sun warmed his back, for a growling grizzly to leave and let him climb down. Each morning he spent in the mountains — as he’d watched the sun rise over the horizon to give light, color, and life to the sky, ridges, meadows, and trees — nature touched his soul. “The mountains are our cathedrals, the stars are our candles, the sun is our gold, and the moon is our silver,” Smoke told me before the trip with my husband. His dark eyes had glowed both with love for the land and sadness that he would never see it again.

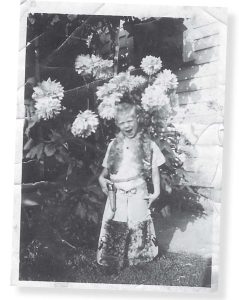

Smoke was a fan of the West even as a 5-year-old boy in Ohio.

The Barn

Smoke and I are an unusual pair. He, a living legend of the West, is well-known and respected for a lifetime of guiding thousands of people, including U.S. senators, Salish elders, and CEOs — as well as shoe sellers, teachers, and farmers — deep into the Bob Marshall Wilderness on horseback. Across the U.S., millions have watched the PBS documentary 3 Miles an Hour chronicling his life outdoors, and many have learned from him to pack their gear on a horse or mule. I, on the other hand, am an academic from Germany and a mother of two who listens and loves to write.

We met on a cold January day six years ago, bonding over horses and mules. The ink on my teaching contract for the University of Montana had barely dried when I signed up to be a student in Smoke’s packing class. On the half mile downhill from my house to his, I post-holed through thigh-deep snow, excited and anxious, breathing heavily in the cold air. When the old stone barn appeared, I traveled both home and back in time.

Smoke taught his first horse- and mule-packing class at the Missoula Fairgrounds in January of 1964.

Just like the old storage barns where I grew up in rural Germany, one side of the thick walls made from small boulders was dug into the hill, built to keep everything inside at an even temperature in both winter and summer. Behind the red door, it smelled like worked leather and metal, earth, dust, and age. Old farm equipment was organized with familiar care. The tools for most immediate use — brooms, shovels, halters — were within quick reach by the front door.

Experiencing unexpected familiarity, I cleaned the snow off my boots and entered the next room, welcomed by a crackling wood stove, a friendly “come on in,” and a firm but smooth handshake. Five-foot-nine and a former college football player then in his mid-80s, Smoke was friendly but deceivingly serious. His gray cowboy hat, jeans, and shirt were spotless; his boots were well-used. The missing top of his right ring finger seemed an omen of adventure and overcoming hardship. As the other students entered, he scanned each one with a swift lift of his hat and the quick, deep glance of an experienced teacher and horse buyer. He instantly knew who brought the curiosity the class requires. “People are like horses and mules,” he later told me. “When they show curiosity, they are smart and can learn anything.”

Learning the Ropes

Smoke likes to say that anything can be packed on a horse or mule safely if you know how to do it. After writing his life’s story and watching him for years teach packing and advocate for the preservation of his roadless home with the same quiet, passionate patience, I know it also takes the right person.

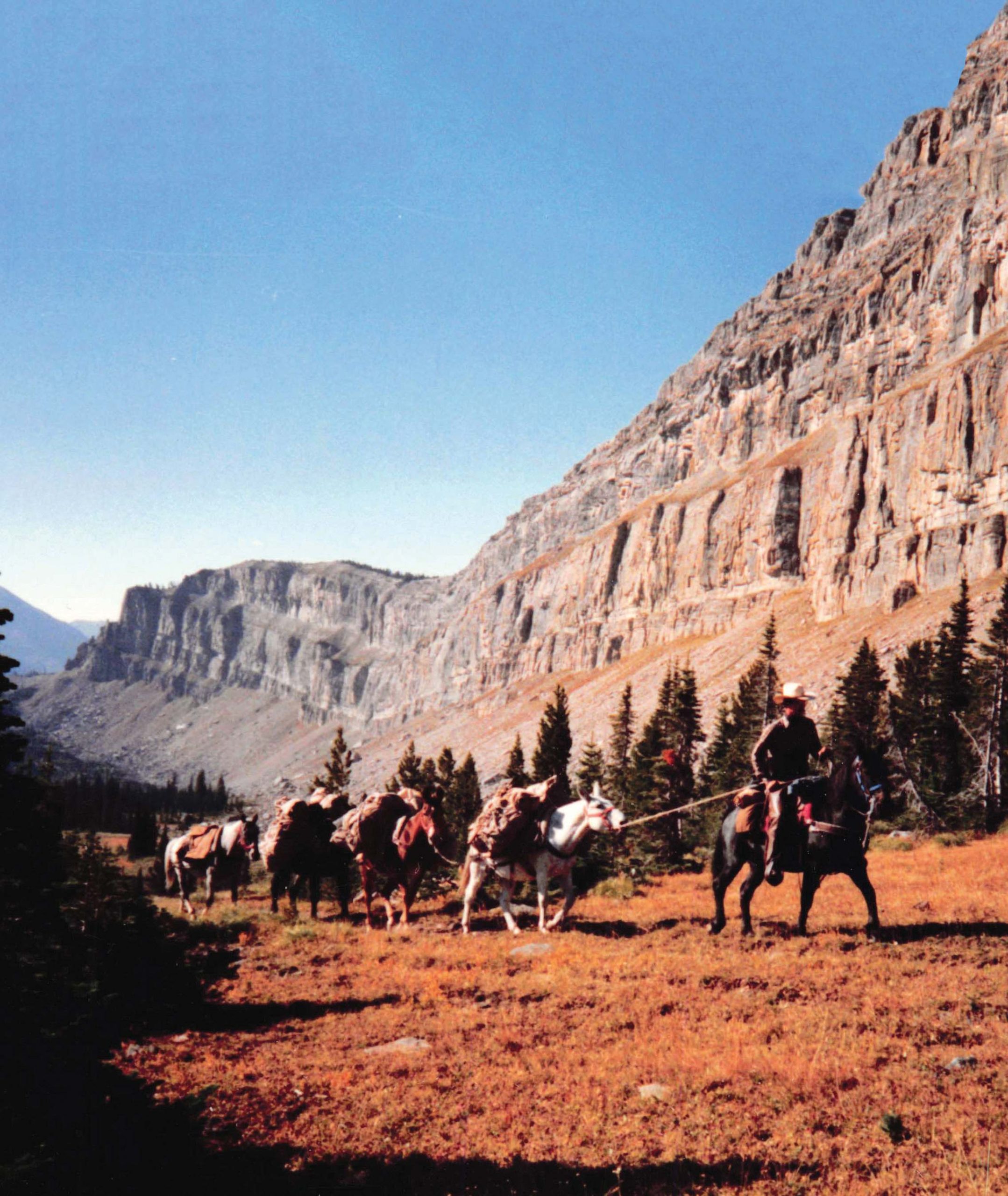

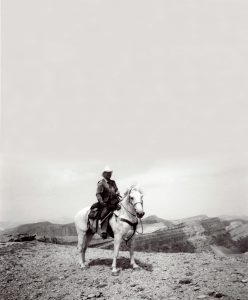

Smoke sits atop his horse Stony as he crosses the top of the Chinese Wall in the Bob Marshall Wilderness.

In the past 60 years, over 30,000 students have learned from Smoke. Within just a few days, he taught the U.S. Navy Seals and U.S. Army how to pack heavy artillery on a mule for war and employees of the U.S. Forest Service and National Park Service learned to load lumber, food, and firefighting equipment. After a few weeks, soon-to-be outfitters and university students learned to pack their food, camping gear, and clothing, nearly perfectly balanced on each side of the animal and never exceeding 20 percent of its total body weight.

It took me forever to learn how to tie off ropes correctly. Patiently, Smoke talked me through the process, letting me become comfortable with the struggle and knowing exactly when to pepper in a story to lighten the load. Suddenly, we were transported out of the barn, huddling around a campfire. Sometimes it was raining, one time even snowing, but more often the stars lit the dark sky like they can only do in wild places, and the work we were doing to get there was worth it.

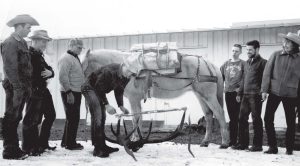

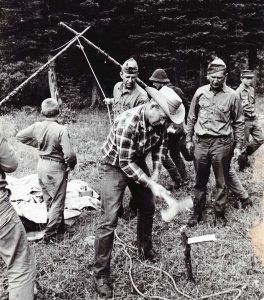

Smoke (in front), an Eagle Scout, sets up camp for a group of Boy Scouts from Missoula.

After years of academic brain work, hours of repeated practice in the barn, many trips in the mountains, falling packs, and finally teaching packing to my own students and kids, I eventually learned the skill. But Smoke’s stories left me with a deep sense of both urgency and purpose, a nagging feeling that they, too, just as the packing and the land, deserved to be preserved and that I, however unlikely, was the one to do it.

Stories from Home

Since my first meeting with Smoke, I’ve spent many days comfortably sitting by the wood stove in his barn, transported to all corners of the Bob Marshall Wilderness. Like a blank page, I was the latest new guest he could show his home, with whom he would share the mountains, flowers, animals, and history of the people who traveled the trails long before us.

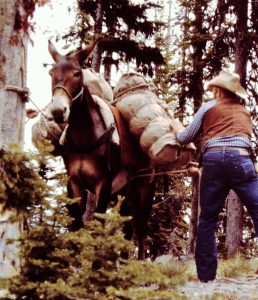

Smoke checks the correct balance of packs on Poky, the mule, on Camp Pass.

Smoke shares his stories in details as big as life, and through his words, I met my first grizzly on top of Scapegoat Mountain and fished with a group of Boy Scouts for trout in the deep, clear holes of the North Fork of the Blackfoot River. The hair on my neck stood up with the scream of a mountain lion as Smoke stumbled through the bushes on a rainy night on Camp Pass, looking for that missing hunter. I sat next to him when, in the late 1960s, a U.S. senator called his name, and he testified with shaky knees for the first citizen-initiated wilderness area in the U.S. I watched people who would otherwise never visit wild places travel at 3 miles an hour, the pace of a walking horse, to share Smoke’s love of the land, animals, and people because his crew made them feel safe and comfortable outdoors.

Smoke leads a string of mules across the South Fork of the Flathead River near Big Prairie Ranger Station in the Bob Marshall Wilderness.

Eventually, he told me about his life, unexpectedly reminding me of my own story of finding a home. Growing up with meager resources, raised by a single mom in rural Ohio, he came to Montana to go to college, fight wildfires, and be a forester. Somehow, he always found a job, worked harder than he should have, and barely made ends meet, but still enjoyed himself and met the love of his life.

As a family, Smoke and Thelma built a successful outfitting business in Missoula, Montana. He seldom left the mountains between late spring and fall; she successfully juggled the kids, logistics, and food. Later, when the kids were older, Thelma guided her own trips. When Smoke and Thelma eventually retired and sold their business, the U.S. Forest Service had permitted them to operate enough days in the Bob Marshall Wilderness to sustain two or three outfitting businesses. Wild places sustained his family and a life Smoke loved; protecting them today is his way to give back.

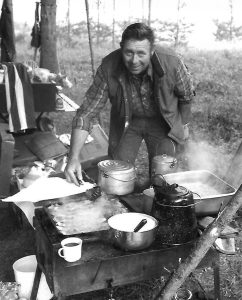

Smoke was the cook on most of his guided trips: Here, he prepares breakfast.

Wild Places

Up on the marshy mountain meadow, my husband and I let our horses graze while we look around, the soft ground squishing under our feet like a sponge. From the bowl of lush grass and flowers, the mountains gently rise to hazy peaks. The blue sky slowly turns orange with fresh wildfire smoke. A few green alpine firs stand tall in the center. Around us, only black stumps remain where a once-thick forest hid a large canvas tent, carefully set up north to south with enough room for four guides, six hunters, and a kitchen. I can see how mindfully the campsite was chosen. Just a few hundred yards below the pass, the wind conveniently dropped the snow just behind the tent during a storm.

A string of guests and mules packed with gear head up Indian Creek toward the Chinese Wall.

A few years after Smoke gave up his business, a fast, big, and hot wildfire swept over the mountain, sealing the earth. He never saw his old hunting camp again. And, after thousands of miles in the saddle, his hips and knees set the limit that he did not dare to admit.

Since that first day in the barn, I’ve visited his old campsites in the Bob Marshall Wilderness without him, but he never leaves my side. I take my husband’s hand as we walk toward the ridge where the snowbrush, stimulated by the fire to grow plentiful, glows in all shades of red. I never wanted to leave Europe — the languages, culture, my family, and friends. I still love all of it. It was my husband’s infectious love for the mountains that swept me away, let me know it was time to go.

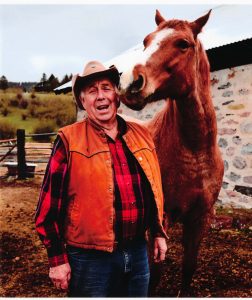

Author Eva-Maria Maggi (left) met Smoke at one of his horse- and mule-packing classes and recorded over 800 hours of his stories over seven years.

The memory of watching the sun rise over these mountains for 50 years makes Smoke get up in the morning. Not surprisingly, he failed at retirement. At 90, he still takes care of his mules and works on the ranch each day, patiently teaching people how to pack anything on a horse or mule, sharing the magic of wild places in his stone barn with the red door. The curious ones come back more than once, or they read our book, Hush of the Land: A Lifetime in the Bob Marshall Wilderness, to join Smoke’s campfire and saddle up for one last trip into the Bob Marshall Wilderness.

Eva-Maria Maggi, who holds a doctorate in political science, is an author, social scientist, and teacher. Her new book, Hush of the Land (Bison Books, 2024), is about conservationist Arnold “Smoke” Elser. She grew up in Germany, lived in Italy and Morocco, teaches at the University of Montana, and calls Missoula, Montana home.

No Comments