25 Sep Round Up: Reel

During the COVID doldrums and lockdowns of 2020, documentary filmmaker Dee Garceau needed a project to shake off cabin fever, as Montanans refer to the condition prisoners call “stir crazy,” and clinicians diagnose at its worst as “psychopathology.”

“I was isolated, depressed, and miserable,” Garceau says. “I needed to go to work.”

At about that same time, Garceau began considering the parallels between COVID and the 1918 influenza pandemic. After a year of research, six months of writing grants, six months of production, and nine months of editing, she finished her 55-minute film, Blue Death: The 1918 Influenza in Montana.

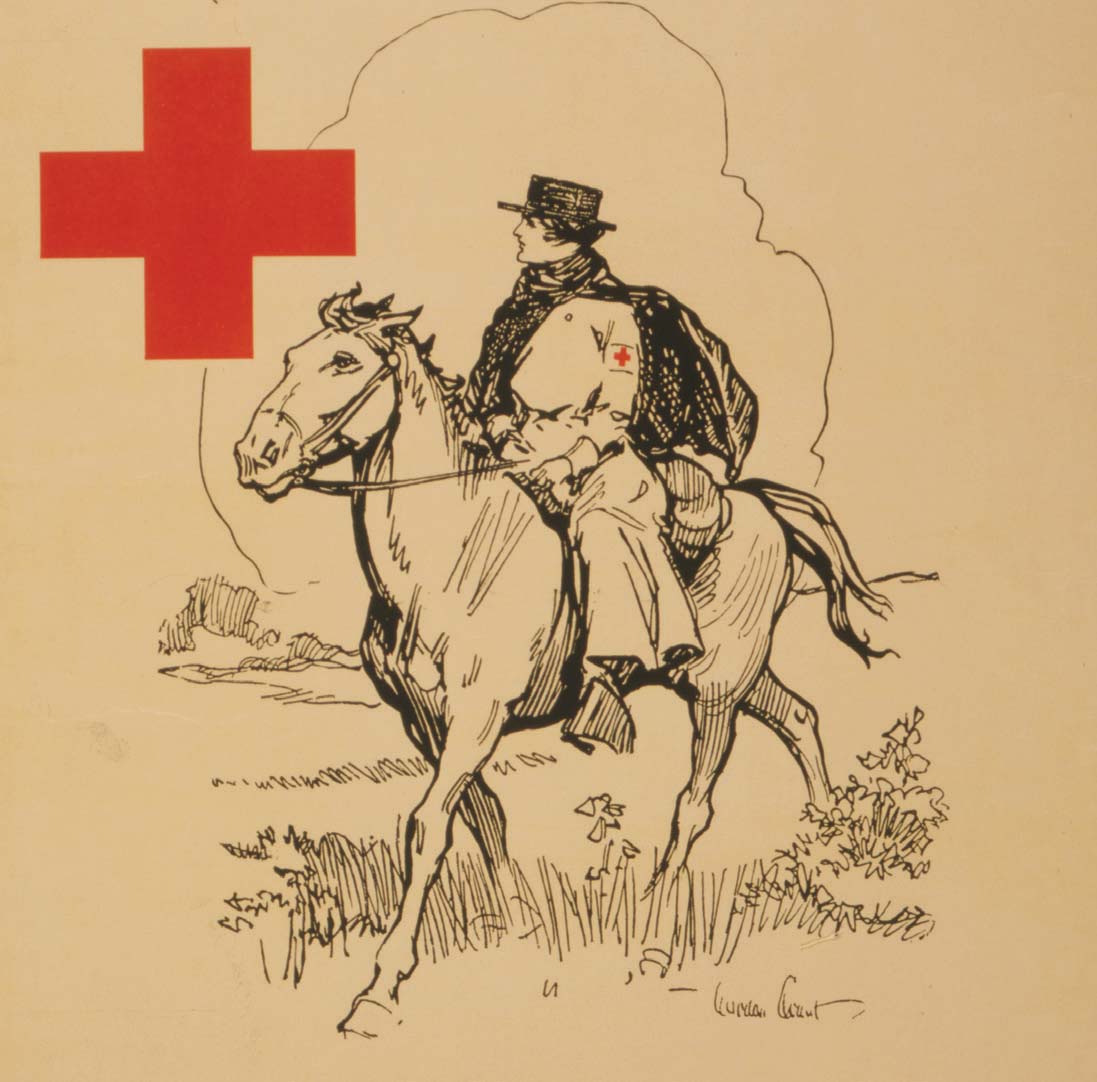

Soldiers returning from World War I unwittingly brought the influenza virus with them. | COURTESY OF MONTANA HISTORICAL SOCIETY DIGITAL ARCHIVES

While many books and films explore the 1918 pandemic, which killed 675,000 in the U.S. and somewhere between 21 and 50 million people worldwide, Garceau’s film focuses on its effects in Montana, where between 4,100 and 5,000 died from the virus. She structures the film around six Montanans’ biographies and how they were affected by the flu. The vignettes represent the spectrum of ironic, sad, courageous, tragic, and always interesting, tracing the geography of the drifting virus like a dark storm over the state.

With a doctorate in American studies from Brown University, Garceau’s research skills are sharply honed. She produced five award-winning documentaries before Blue Death, and for her latest film, research was funded by Humanities Montana, the Greater Montana Foundation, the Montana Film Office, and Treasure State Studios. In March 2024, the documentary won Best Feature Film in Toronto’s Wildsound Film Festival.

“The joy of creating documentaries is getting to know my source people,” Garceau says. “They become lifelong friends. And they give me the opportunity to explore humanity while honoring our cultural and historical differences.”

One of her sources, Leon Rattler, especially enjoyed helping Garceau’s team set up filming a buffalo herd. He thought it was too dangerous to be filming from the highway, so he called his friend, who manages the bison and was able to set the camera crew up among the herd. This was also a highlight for John Nilles, the film editor and director of photography. “We got to go into the middle of the herd, where we set up the cameras next to our pickup, and the bison quietly grazed right up to us,” he says. “The beauty of Glacier National Park’s purple and blue mountains stood behind the golden grass of the prairie.”

The Blackfeet Crazy Dog Society organized its own chapter of the Red Cross to educate people about masking and quarantine. | COURTESY OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, PRINTS AND PHOTOGRAPHS DIVISION

Germane to her style and dissimilar to most documentaries on the 1918 pandemic, Garceau devotes only obligatory time to the pandemic’s international path of devastation. Instead, she focuses the greater part of her screen time on her Montana vignettes. Although many states had far greater numbers die from the virus — Pennsylvania having the most at 60,000, and Georgia with almost 31,000 — Montana’s per-capita death toll ranked sixth in the nation. One theory proposes this rate was so high because the population for the draft was overestimated, and with 40,500 Montanans serving in World War I, a greater number per capita returned to spread the virus.

Blue Death: The 1918 Influenza in Montana was shown in nine Montana communities this summer and is now available to stream through Montana PBS at pbs.org/show/blue-death.

No Comments