01 Aug Complex Expression

I’ve been making assemblage work for 50 years,” says Stephen Glueckert, an artist and educator based in Missoula, Montana. “But I draw, and I paint, and I play music, and, to me, the older I’ve gotten, the less I see lines between these things. I think it’s a flaw in our education system that it channels people — you’re going to be a painter, you’re going to be a ceramic artist. And then, you sell yourself short. You can’t deny who you are, whoever it is.”

Macro details abound in these mixed-media works from Stephen Glueckert, Grace Brogan, and Tyler Macko (left to right).

Mixed-media art throws the doors wide open, and for the creative people who find their calling here at the intersection of disciplines, the opportunities are endless. “Part of the magic of mixed-media art,” says Nikki Todd, owner of Visions West galleries in Bozeman and Livingston, “is that there’s really no limit.”

Often trending toward collage, assemblage, and sculpture, mixed media is a catchall term for any artwork composed from multiple mediums. For artists like Glueckert, who resist being siloed, the lack of material constraint offers an opportunity to embody their vision fully. “[Mixed media] has all these layers and depths; you can mix all these messages in, and it has a different dimensional aesthetic that painting or drawing doesn’t always really imbue into the work,” says Todd. “I feel like mixed-media work is often tactile and engaging and has more of an intuitive quality because the artist has figured out how to piece things together.”

The wealth of detail and diversity of items in Tyler Macko’s Common Measurement begs close inspection. Photo by THE VALLEY TAOS

That intuitive sensibility drives three Montana-based mixed-media artists: Tyler Macko, Grace Brogan, and Stephen Glueckert. While working in different techniques and mediums, all three quickly reference a deeper need to make work that “feels right,” whether for personal, social, ecological, or historical reasons. All three also stress how important it is that their work feels accessible and intriguing to the viewer or user, an unassuming invitation to explore, play, tend, or ponder.

Tyler Macko

“My work is about trying to understand being, in general,” says Tyler Macko of his assemblages. “I’ve always been fascinated with anthropology and genealogy and folklore — prehistoric handprints on cave walls. Making a painting is doing the same thing they were, recognizing you’re in this existence and trying to figure it out in whatever way you can.”

Citing the notion that some objects have a certain presence or feeling, Macko gathers bits and pieces as he goes about his daily life in Wilsall, where he works on a ranch. “You just collect all of these objects and put them into one, where it feels like a singular thing again. There’s this elusive, ethereal thing that flows through you, that creates the piece,” he says. “If you can stop making decisions and let it happen, it usually works out the best way that it can.”

Cave Between The Ears | COTTONWOOD BARK, PLYWOOD, BONE, FOUND OBJECT, OIL, AND ACRYLIC | 65 X 75 INCHES | Employing made and found objects in a painterly way, Macko creates distinctive art-is-for-everybody assemblages ranging in scale from diminutive to grand, as with Cave Between the Ears. Photo by LEILA SPILMAN

The sheer diversity of items in his work speaks to his openness to whatever the world tosses his way: an arrowhead, a length of rope, plaster, newsprint, a bedsheet, motor oil, carpet, liquid nails, melted pewter, an axehead, a Raggedy Ann doll, pennies. His egalitarian approach to materials applies to his thinking about art and audience as well. Though paint plays a small role in many of his works, he still calls his pieces “paintings,” largely because, as he clarifies, “I don’t like the patriarchal, walled, guarded aspect of the art world. It really bums me out. And I don’t want there to be a barrier of entry for anything I produce. Yes, they’re ‘assemblage,’ they’re ‘found-object art.’ But I never want them to seem more fancy than they are. People try to make art this very academic thing, but it’s for everybody.”

He also mentions that, in his process, he often utilizes objects or shapes — whether made or found — in a painterly way. “With a painting, you just mix up a green shade and make a green stroke. I feel like if I need a stroke, I’ll either find it or make it. I’ll cut out a piece on the bandsaw or jigsaw and make the stroke rather than painting it.” In this way, his pieces are assembled, layer by layer, much like a painting would be, but with additional depth and context based on the juxtaposition of objects.

Fingers Made of Purple | PLYWOOD, FOUND OBJECT, OIL, AND ARROWHEAD FLAKE | 48 X 40 INCHES | Macko’s work makes particular use of items he finds around the Wilsall, Montana ranch where he works. Photo by LEILA SPILMAN

Raised in Ohio, Macko draws inspiration from the motifs of his childhood, as well as the landscape in which he lives. “Montana has inspired me in a lot of ways. It’s a very humbling place to live — there aren’t many barriers between you and the ever-present greater cycle of things — and you very much have a kinship with a rock or tree or river,” he says. “You’re part of the landscape.”

Vertebrae gathered in a field will likely find their way into one of Macko’s future pieces. Photo by LEILA SPILMAN

And, while his art doesn’t directly depict Montana’s grandeur, he hopes it can evoke a similar feeling. “A field is the most perfect-looking thing. You’re never going to be able to make anything that perfect. And, on a fundamental level, if I can make anything that feels anywhere close to as nice as that field does, I’m doing my job.”

Grace Brogan

A broom may not immediately conjure thoughts of fine art, but Grace Brogan of Missoula wants us to question that notion. “I find it really fun to play on the spectrum of functional to less-functional,” she says, “or I like to think of it as ‘alternative-use.’ It’s still based on something that can be used every day, by a person, in a really normal, ubiquitous way. Just sweep your house, and it should do its job for many years. But it’s also useful for the eyes or the heart or the soul.”

Grace Brogan sits alongside some of her brooms at the Moon-Randolph Homestead near Missoula, Montana, where she was an Open AIR Montana artist in residence in 2022. Photo by RIO CHANTEL

As a skilled traditional broom maker (or broom squire), Brogan has long been interested in blurring the lines between objects seen as purely functional and those that are viewed solely as art and hung on a wall. “I studied art in college, and there was a really strong functional pottery program there,” she explains. “So I think my eventual interest in broom making was carried by that foundation in functional pottery, the notion that you can have beautiful things in your life that are made by humans and support peoples’ livelihoods, feel good in your hands, and work really well.”

Building on the basic broom-making skills that she learned at North House Folk School in Minnesota and then furthered at several other folk schools throughout the country, Brogan has spent the past 15 years developing her own signature style within a discipline that has deep roots and traditions.

Brogan’s brooms are made from broom corn, a variety of sorghum. Photo by RIO CHANTEL

For Brogan, this means pushing the envelope with materials and style. Why opt for a straight broomstick when you could use a crooked, gnarly branch shaped by age and elements? Or perhaps a burl? Or an antler? Drawing on her background in ceramics, Brogan also makes broom handles from clay and fires them in a local wood-fired kiln, a lengthy and unpredictable process that imbues pieces with the marks of many days spent in the kiln.

Playing on the spectrum between fine art and functional tools, Brogan often utilizes unexpected materials, such as this section of burl. Photo by RIO CHANTEL

This attention to material has always been a primary focus for Brogan. “My interest in materials, and my personal desire to be a responsible human, has made me very interested in sourcing,” she says. “What is the chain that brings you material? Where is it coming from? What is that process? I’ve gone down other art avenues and haven’t continued because I’ve asked myself, where does the pigment come from in this paint? Or because I didn’t want to support a leather industry that really is not great.”

Requiring only hand tools for construction, brooms can be made anywhere, even in a wall tent. Photo by RIO CHANTEL

While not perfect, broom making allows Brogan to make sourcing choices that she’s a lot more comfortable with. Part of this means making or gathering handles herself, but part of it also means bringing the supply for her broom corn (the variety of sorghum used for brooms) closer to home. “I have a personal interest and background in sustainable agriculture — not just for food, but for fiber as well — so tapping into that curiosity is fun.” With the help of three Missoula-area farmers, she’s been working for the past six years to grow and selectively propagate different varieties of broom corn that thrive in Montana’s dry climate. “Ideally, I could someday, or for special projects, use all local materials: local clays, locally sourced wood, local broom corn. That would be amazing. And the fact that that isn’t too far of a reach is one of the many things that has kept me focused on broom making.”

Stephen Glueckert

“The first assemblage pieces that I had the courage to share with an audience were from 1976. One of them is still in my house, and the other is in a private collection in Billings,” recalls Stephen Glueckert. “They’re moveable, they’re participatory, and I still stand behind them.”

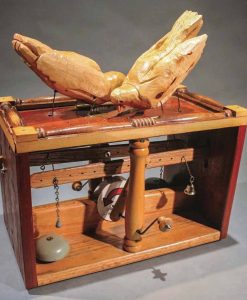

Two Birds | STEPHEN GLUECKERT | MIXED MEDIA | 20 X 22 X 12 INCHES

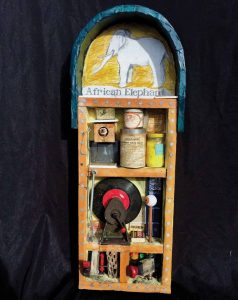

African Elephant | STEPHEN GLUECKERT | MIXED MEDIA | 36 X 12 X 5 INCHES

An artist based in Missoula with a wide diversity of talents and interests, Glueckert is perhaps best known for his kinetic sculptures that invite the viewer to engage — by turning a crank or pressing a lever. Often whimsical, frequently poignant, always clever, these sculptures ask an audience to consider the artist’s viewpoint. “I realized that if I put a crank on a piece of art and a person goes up and cranks it, that person is in the perfect position to view the piece. I have moved that person to the right position,” he says. “And when a person is touching an object, they’re viewing it from the perspective of the maker. … It’s being handled: It’s not something that’s seen from afar and not experienced. And that’s really important to me.”

Stormy Weather (version i) | STEPHEN GLUECKERT | MIXED MEDIA | 12 X 12 X 12 INCHES

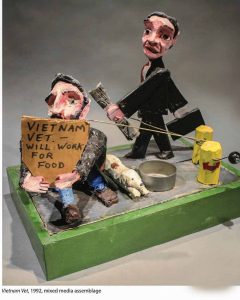

Vietnam Vet | STEPHEN GLUECKERT | MIXED MEDIA | 16 X 12 X 14 INCHES

Glueckert has had a long and rich career as an artist and educator, and just as he blurs the lines between artistic disciplines, it’s clear that his teaching and artistic practices have profoundly influenced each other over the decades. After working in schools in Papua New Guinea, he says he came to the realization that “most of what you’re doing in education is addressing the students’ self-esteem. You’re part of a cocoon for their self-identity. You’re not there to teach them one- and two-point perspectives. That’s secondary. And that transfers to my larger thinking … we need to know what we stand for, and to serve as a cocoon for safety and civility.”

Glueckert’s work often carries subtle or not-so-subtle social or political messages, and he nudges the viewer to think critically about the world around them. “You can only be who you are, and I think of myself as a realist. So I’m not making shit up,” says Glueckert. “But I am observing, and I am moved by injustice, or how we can do better. How can we be better? And not that I feel like I have a lot of answers, but I think it’s really good to ask those questions. It helps me wake up each day and move on.”

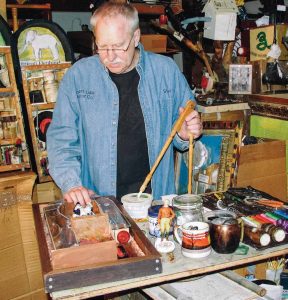

With a significant background in both art and education, Stephen Glueckert merges the two in the often socially and politically charged works he creates in his Missoula, Montana studio. Photo by BEV BECK GLUECKERT

With its cartoonish figures and array of found objects, Glueckert’s work is often compared to folk art, and he’s okay with that. “The meaning of ‘folk artist’ is art of the common person. I embrace that. Does it mean because you’ve been through the academy, you’ve abandoned the folk? That is an elitist notion.” He proudly touts his upbringing in Great Falls and his hardworking parents as his biggest inspirations. “I grew up working in the steam laundry and on the farm in the summertime, and when you’re driving the baler, there’s this calm, and you’re just staring at it while you’re out there baling thousands of bales of hay. I was inspired by the machinery in the laundry. And by my father, who was a gifted machinist, and I’d go down and work with him as a kid.”

Drawing on his mechanical aptitude, compassionate viewpoint, smart observations, and resistance to being pigeonholed, Glueckert has made a career of following his heart — just as he hopes everyone will, especially other artists. “You can only be who you can be. This is in me, and if people give you some shit, that’s OK. That just makes me more entrenched in carrying on. If you feel like you’re going to have a breakdown if you don’t do it, you’d better do it. Just jump in and do it.”

Melissa Mylchreest is a freelance writer and artist based in western Montana. When she’s not at her desk or in the studio, you can find her enjoying the state’s public lands and rivers with her two- and four-legged friends and family.

No Comments