01 Aug Bringing the Splendor of Montana to Life

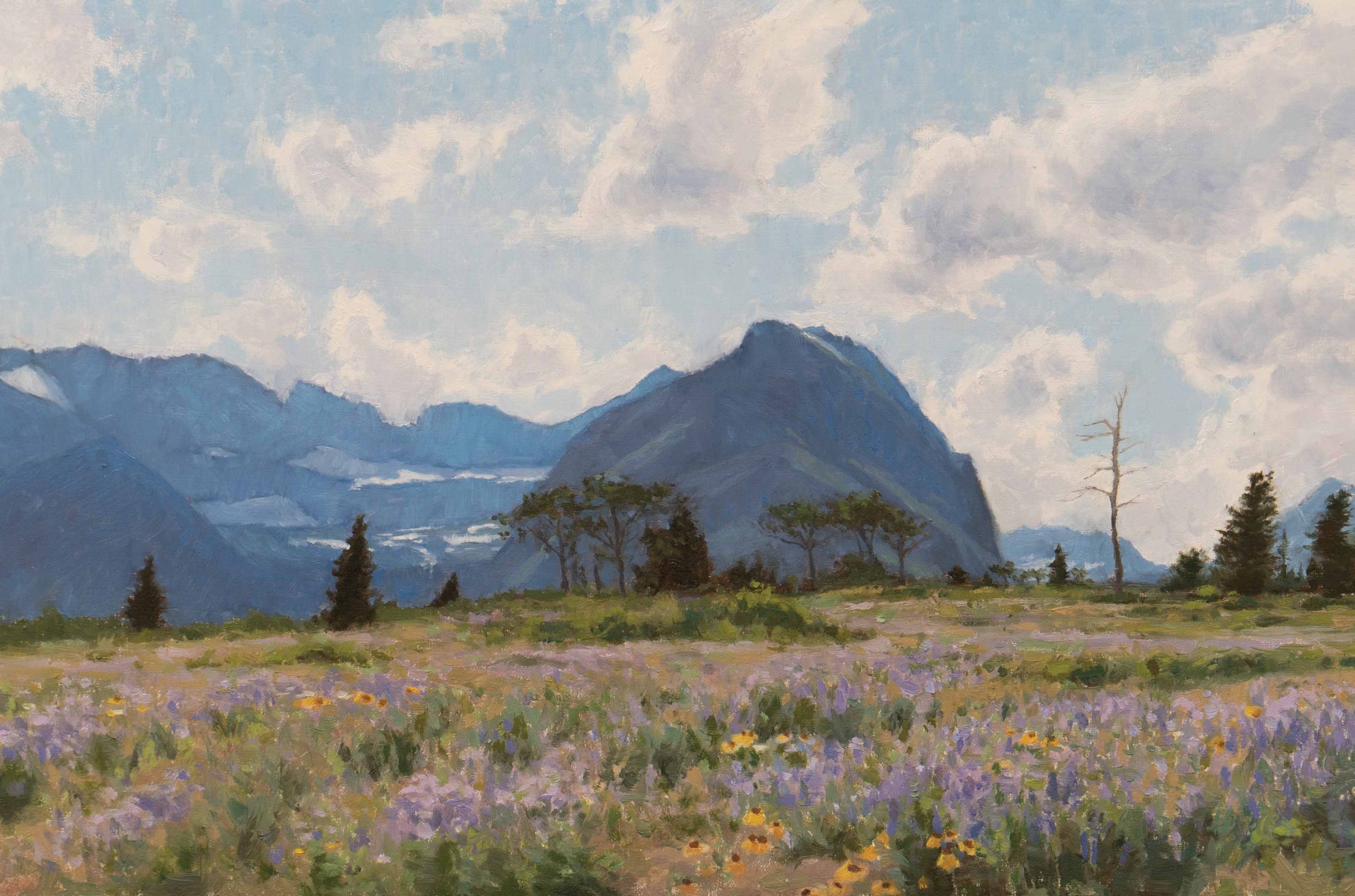

Born and raised in Whitefish, Montana, painter Nate Closson has always been enthralled with the state’s beauty. His art is a tribute, a way to reignite appreciation for the region’s landscapes and lifestyles.

“This whole world is beautiful, but nowhere more so than Montana,” Closson says. “Sometimes that beauty can be overlooked — when it becomes part of your everyday. We get caught up in life and can become immune to these amazing things that surround us.”

August | OIL ON PANEL | 36 X 32 INCHES

Closson’s mother, watercolor artist Bonnie Closson, homeschooled him, so art was an inevitable and welcome part of his life. It was only natural for him to meld his creative passion with his love of the Treasure State.

“I grew up drawing and painting — we were always doing art stuff,” recalls Closson. “One of my earliest paintings was of Big Mountain; I think my mom has it in a box somewhere. I was only 6, but I remember thinking that it turned out really well.”

His father-in-law, artist Sutton Finch, was another influence. “Sutton was one of my art heroes,” says Closson. During his senior year of high school, Closson entered — and took first place in — the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service’s National Junior Duck Stamp Contest. He speaks fondly of Finch helping with his entry by offering guidance. “His jaw was wired shut, having been kicked in the face by a horse, but that didn’t keep him from telling me what he really thought,” Closson says with a laugh.

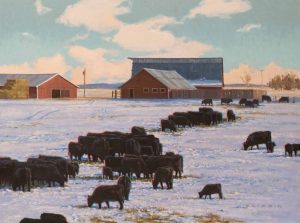

New Calves | OIL ON PANEL | 30 X 40 INCHES

This early encouragement and exposure to art gave Closson a strong foundation in drawing and design, and a love for all things creative. He started painting landscapes, which led to adding more rural elements, such as barns, horses, and cows. “I find that adding these visual elements to the landscape tells a better story and makes the piece more intriguing. For me, it’s about painting a scene that someone else can inject their own personal moment into. When you create something that someone else can connect with, well, that is pretty powerful.”

He refers to New Calves as an example. “Driving home from Great Falls, I was drawn to this silhouette of a barn and all of the dark cows against the snow,” he says. “When I painted it, I took an abstract approach to the mass of cows — so I wasn’t copying the image per se, more or less interpreting it.” When he showed the finished piece in a gallery, a woman approached him with tears in her eyes. “She told me this beautiful story about how the painting brought back warm memories of her family farm,” he says. “That’s kind of the goal. You create the scene; someone else creates the story.”

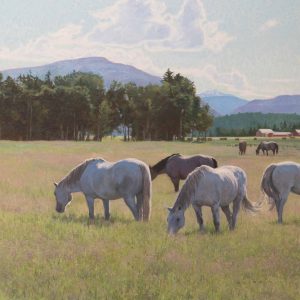

The Grey Horses | OIL ON PANEL | 48 X 48 INCHES

Through his art, Closson enjoys bringing the resplendence of Montana to life.

“Nate’s love for rural Montana shines through his work,” says Monica Pastor, owner of Underscore Art Gallery in Whitefish. “He captures the essence of what we love so much about living here. His attention to detail and craftsmanship are incredible.”

Before painting full time, Closson worked as a cabinetmaker with his father, and he draws on that skillset today: The two build all his frames, which Pastor says “are works of art in themselves. They all work so well together to create a really complete piece.”

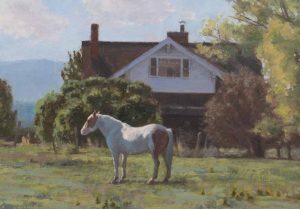

Closson strives to remind viewers of the splendor of the natural world. “Grey Horses is exactly that,” Closson explains. “It’s a field that I often drive by twice a day when I take my kids to visit their grandparents. It can be easily passed over, but I wanted to capture its wonder. Life happens, things change; I think we need to enjoy what we have while we can.”

Above Interstate 90 | OIL ON PANEL | 24 X 36 INCHES

Beyond portraying the beautiful, Closson has a keen eye for authenticity. “Nate’s work expresses an intimate and quiet view of Montana,” says Michelle Cassens, owner of Cassens Fine Art in Hamilton, Montana. “He paints farmlands and animals in a really unique way. He understands the architecture of the buildings, the bone structure of the animals, the depth of the landscape. I appreciate his accuracy — but also the calm, ethereal feeling he creates.”

Closson says this approach is driven by his curiosity about family history. “My mom grew up on a ranch in Havre. My grandfather died when she was 18, so I never met him. I guess maybe there’s a bit of family lore that drives my work,” he says, adding that he’s always wondered what his grandfather was like.

The artist’s rural Montana lineage is a strong foundation for his creativity and melds with his present-day. As the husband of a Grand Prix show jumping rider, he now spends a lot of time around horses and equestrian events, which further inspires him. Rather than painting horses and riders jumping in midair, though, he opts for smaller, quieter moments around the stables and show grounds.

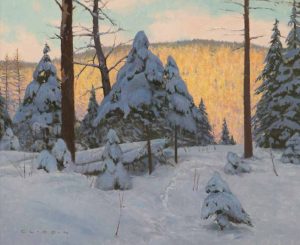

Winter’s Solitude | OIL ON PANEL | 24 X 30 INCHES

Since his first year of college in San Diego, painting en plein air has played an important role in Closson’s work. “I like to think of them as ‘art pushups’ — an opportunity to go out and exercise your art brain,” he says of these pieces. “One of the drawbacks of working in a studio is that it can lead to becoming overly dependent on photographs. Plein air is about getting out and painting the real world in real time. You go out and find what you like and translate it verbatim. It’s an opportunity to observe things such as light and focus as they really are. I feel it’s important to be literal with plein air; there’s really no sense in being out there if you aren’t going to capture what you see.”

Closson often uses his “art pushups” to inspire and inform larger pieces he designs in his studio. “Painting large pieces outside is kind of difficult and really too much to manage,” he says. He enjoys the process of designing these larger works in his studio and the flexibility it provides in terms of being both realistic and stylized; it allows him to play with the elements he has observed.

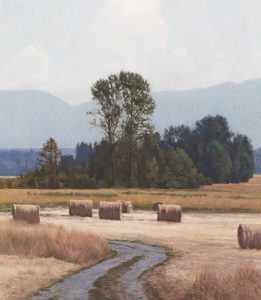

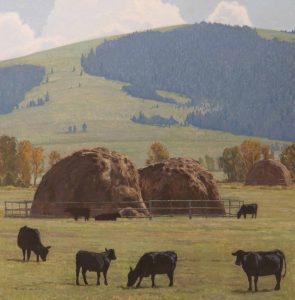

Loose Stacks and Angus | OIL ON PANEL | 48 X 48 INCHES

Loose Stacks and Angus is an example of how Closson fuses together various source materials to build a scene. “There are just a few places in Montana that still do loose haystacks; one of them is outside of Avon,” he says. “I added the cows and played with how they are arranged. It creates a different style versus just copying a photo — it’s a little more impressionistic. There is no implicit story; you can imagine any kind of backstory to the scene.”

“One of the things that sets Nate apart is his ability to tackle scale,” says friend and painter Kenneth Yarus. “He never shies away from painting large pictures, which takes a lot of gumption. Large works can be challenging, and they’re hard to do well — but Nate just goes for it. And he isn’t afraid to do what he needs to do to make them great.”

Closson and Yarus will often paint and take photographs together, along with their friend, artist Richie Carter. “The painting world can be an isolating profession,” says Yarus. “Having like-minded people like Nate and Richie as compatriots is a wonderful thing for me. Sharing time and space with them is like a superpower that makes me a better painter.”

“Ken and Richie keep me honest,” says Closson. “I know they will tell me what they really think. And it’s great to get a candid critique.”

Above Interstate 90 is one of the pieces spawned from their excursions. “I was driving with Ken one afternoon. Often, I’ll hold my camera out and shoot at things; the images usually come out blurry and awful. But I saw this guy on a tractor coming over the highway, and I captured it. For me, it illustrates where the Old West intersects with the new — both are still very present in Montana and are overlapping.”

The Farmhouse | OIL ON PANEL | 9 X 12 INCHES

The same could be said in his studio. It’s not unusual for Closson to be working on multiple pieces in various stages of production at one time. He prefers working in batches. “It makes me feel more efficient in solving the challenges that arise,” he says. “If I get stuck somewhere, I can step away and switch focus to something else while I continue figuring out how to solve it.”

“One of the lessons I learned early is to keep painting,” Closson adds. “There will always be things that are frustrating and difficult to solve, but you’ve just got to keep painting.”

Christine Phillips is a freelance writer based in Whitefish, Montana. She enjoys writing about art, architecture, design, health, and outdoor recreation. When not playing with words and working with her clients, she loves hiking, biking, snowboarding, taking care of her two little dogs, and teaching Pilates.

No Comments