24 Nov Outside: A New Era

At the end of last winter, with the final days of the ski season fast approaching, there was a mad dash for tram rides at Big Sky Resort in Montana. The ski area’s iconic lift — installed at the top of 11,166-foot Lone Peak in 1995 — was nearing the end of its life. Mid-winter, the resort announced that a new, larger, state-of-the-art tram would soon replace the aging original, and skiers from all over flocked to Big Sky for one last ride.

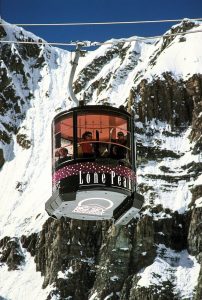

The old, cylindrical cabins held about 15 skiers and took on different designs over the years.

There were celebrations, seemingly for weeks. High-fives and cold beers greeted those who waited in the tram line. Local “dirtbags” — skiers who get as many days on the mountain as possible, often sacrificing everything from paychecks to relationships — came out in force, worshiping the tram as a symbol of epic powder days and legendary stories. An era was coming to an end.

The tram was the brainchild of former Big Sky general manager John Kircher, who is credited with the idea of putting a lift to Lone Peak’s rocky summit in the early 1990s. Some thought he was crazy and many called him a visionary, but by 1995, construction was in full swing, and when the tram opened later that year, Big Sky’s reputation for extreme, above-treeline skiing was solidified. (Sadly, Kircher will not see his tram’s replacement; he passed away in January of 2023.)

The tram has given thousands of skiers and snowboarders rides to the top, where several double and even triple black diamond runs lead down. And by down, I mean straight down, no easy way down, and sometimes hard-to-find-your-way down. Simply put, skiing from the top of Lone Peak is not for the faint of heart. The addition of the North Summit Snowfield in 2005 and the opening of the Lost Lake Cirque backcountry area added even more options to the already famous Big Couloir (where skiers must sign out with ski patrol) and expert runs like Liberty Bowl, Lenin, Marx, and the Gullies.

During the summer of 2023, workers constructed the middle tower of the new tram, which rises more than 90 feet above the steep terrain.

Much like Jackson Hole’s famous Big Red — the nickname given to the ski area’s 100-person aerial tram — Big Sky’s highest lift has become synonymous with the resort. The tram has been featured in everything from extreme ski films with pioneers like Scott Schmidt and Dan Egan to viral YouTube videos — the humorous “Altitoot” chronicles a flatulence-riddled tram ride and has racked up more than 330,000 views. Riding the tram is a bucket-list item for skiers all over the world who visit Big Sky each winter in hopes of getting an epic run from the top of Lone Peak.

But, with nearly 30 years of operation, the lift was ready for an update. A team from Switzerland’s Garaventa Lift Group began construction in 2022 and the new lift will open this winter, just in time for the busy holiday ski season. There are many differences between the old tram and its replacement — notably the cabin size. Where the old cabin was cylindrical like a beer can, the new one is rectangular and holds up to 75 passengers instead of the previous capacity of 15.

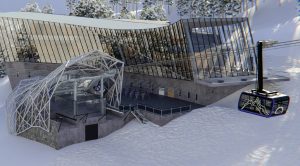

The new location of the bottom terminal, in the bottom of the Bowl, includes sweeping views of Lone Peak.

Returning Big Sky visitors will immediately notice the tram terminals’ new locations. The bottom terminal now sits just below the Powder Seeker lift at the bottom of the Bowl, which means one less chairlift ride to get to the peak. There is also a mid-mountain tower, improbably rising 100 feet above the ridge near the double-back Gullies on the mountain’s sheer east face. The top terminal sits slightly to the north of its predecessor. In addition to significant excavation work for two summers, construction teams poured over 1,300 cubic yards of concrete, installed six tie-back anchors, and placed 114 metric tons of steel at the top terminal.

In the future, the new tram’s upper terminal will include an all-glass platform with panoramic views of the surrounding peaks and a glass floor will give visibility down the fall line of Lone Peak (to be completed in 2024). Summer rides up to the summit — the state’s highest scenic overlook — will be a focus for the resort. Once Big Sky installs the new Explorer Gondola from the base area, which is slated for completion in two years, summer guests can seamlessly access the peak from the base area for the first time. With views of three states, two national parks, and dozens of mountaintops in the distance, there’s no doubt the summit will be a popular attraction.

This rendering of the new terminal at the summit of Lone Peak illustrates the larger cabin and docking station.

Everyone has their own tram story. Mine includes a jarring emergency stop as the cabin approached the summit during my first ride in the late 1990s. The tram car began swinging back and forth, and it was dead silent as we peered out of the windows at the imposing rock face right in front of us and the ground many hundreds of feet below. We sat there motionless for several minutes, nobody saying a word, until the cabin slowly started to move again. At the top, all my fears from the ride up were replaced by other fears, namely trying to get down the mountain in one piece. I’m happy to report that I made it, and, like many skiers and snowboarders, I was hooked.

Admittedly, however, I never turned into a tram junkie. There are many of them out there, skiing the peak every day, no matter the conditions. Locals will say it’s best when the summit is clouded on a powder day, keeping the tourists away and the snow fresh. The visibility may be terrible, but the snow can be amazing. In my 25 years of riding at Big Sky, I consider myself more of a strategic tram rider, choosing my rides based on conditions, timing, and how I feel that particular day. The beauty of Big Sky is in the tremendous variety of terrain: If you don’t want to wait in the tram line, there are endless opportunities for epic runs all over the mountain.

The list of memories is long, though, since that first tram ride many years ago. I’ve been lucky enough to have a few early rides with patrol before the mountain opened. I’ve enjoyed countless deep powder runs and snowboarded in seldom-visited spots only accessed from the peak. I remember the first tram rides for my kids — both were on the peak by the time they were 7 — and their first time down legendary runs like Liberty Bowl, Big Couloir, and the North Summit Snowfield. One of my most cherished memories is when I took my son down a steep chute in the out-of-bounds Lost Lake Cirque on his 11th birthday.

Some memories are reminders of just how harrowing the tram-serviced terrain can be, like the time I had to take off my snowboard and hike back up one of the Dictator chutes. I remember a Liberty Bowl run that was nothing but leg-burning frozen sastrugi, and several times I found myself on steep, bulletproof ice, legs shaking, wondering just what the hell I was doing. The tram can be humbling to even the most die-hard skiers.

The bottom terminal and upper gondola station (rendered here) will be finished for the winter 2025-26 season.

Last April, as winter was winding down, I largely stayed away from the tram. The lines were long, the snow was good all over the mountain, and I was trying to maximize my snowboarding before the season ended. I did get one final ride a few days before the end, a fantastic run down Marx on a sneaky powder day. It was good enough that I debated getting back in line, but it had doubled in size by the time I returned to the bottom terminal. Instead, I moved on, searching for more fresh lines around the mountain.

Some lament the retiring of the old tram, decrying the larger cabin size and the increase in the number of skiers that will be on the summit. It’s a symbol of change that many don’t like or refuse to accept. Change is hard, I realize, especially with something that has been part of our lives for nearly three decades. I have a feeling, though, that when we all take our first ride on the new tram, we won’t be thinking of what has been but will instead wonder at what will be. Especially if it’s a powder day.

Brian Hurlbut is the author of Insiders’ Guide to Yellowstone and Grand Teton (Globe-Pequot) and Montana: Skiing the Last Best Place (Great Wide Open). His writing has appeared in Montana Quarterly, Montana Magazine, Big Sky Journal, Mountain Outlaw, Western Art & Architecture, Outside Bozeman, and more. He lives in Big Sky, Montana.

No Comments