29 Sep Make Way for Motus

Rubber meets gravel as our four-wheel-drive vehicles rumble up a dusty road. We pull over at a wide bend near a hairpin turn. After gathering supplies, avian researcher Mary Scofield and volunteer Lesley Rolls head downslope through sagebrush, while I accompany avian biologist William Blake up an overgrown two-track into a stand of conifers.

As the sky turns a cobalt blue and lights from the town of Lolo, Montana begin to twinkle in the valley below, Blake deftly strings up nets using fingers that have practiced this routine thousands of times before. Once finished with the nets, which are constructed using fine filaments that most birds don’t see, Blake sets a small portable speaker on the ground programmed to play the calls of a nighthawk. Then, he installs the pièce de resistance: a paper cutout of a common nighthawk.

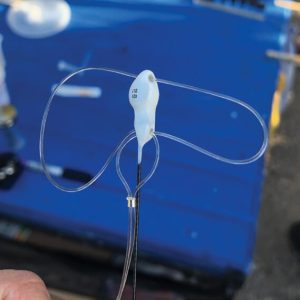

This Motus tag is equipped with nylon loops that fit around a bird’s wings. Photograph by SNEED B. COLLARD III

At first glance, it all appears to be the beginning of just another bird trapping and banding session, but upon closer inspection, it’s clear that this operation is unique. Any birds caught tonight have a chance to participate in a revolutionary breakthrough in the study of animal behavior: a new technology called the Motus Wildlife Tracking System.

Pingers, Pingers Everywhere

As with traditional tracking technology, Motus allows scientists an opportunity to learn more about wildlife movement and behavior. Motus employs a network of stations, or towers, to detect VHF radio signals from ultralight tags that have been placed on target animals. These tags all ping at the same frequency, but each has a unique pattern, allowing researchers to easily distinguish one tag — or one animal — from another. Every Motus station is equipped with multiple antennas, giving it a detection range of 5 to 15 miles, and data from the stations is either automatically or manually uploaded to an enormous database that’s accessible to researchers around the world. The brainchild of Birds Canada, in cooperation with a network of international scientists, Motus’s shining feature is that it allows scientists to easily, cheaply, and remotely monitor when and where animals move.

Fitting a Swainson’s thrush with a new Motus tag is a delicate task. Photograph by SNEED B. COLLARD III

Before Motus, scientists who wanted to track an animal faced limited options, each with significant downsides. They could equip animals with satellite geolocation tags that either cost thousands of dollars each or had to be physically recovered to retrieve the data. Alternatively, they could deploy passive integrated transponder tags that work like the E-ZPass tollway systems used for cars but require animals to come extremely close to a receiver to be detected.

As a third option, scientists use traditional VHF transmitters. Researchers catch an animal, attach a radio collar, then release it. To monitor the animal, scientists go out with a handheld antenna and point it in different directions, hoping to pick up the collar’s signal and eventually determine its location. This method is extremely time-intensive and only works if researchers happen to have a good idea of where the animal might be. The collars are also big and bulky, so they can’t be used for most birds and smaller animals.

The thrush’s ultralight antenna is ready to signal its movements to scientists. Photograph by SNEED B. COLLARD III

“With traditional VHF transmitters, each tag is on a different frequency,” Blake says. “You can’t really set up an automated tower that picks up birds in the middle of the wilderness because it would have to scroll through all the different potential frequencies to hopefully pick up all the birds. Motus works on just one frequency, so you can literally tag thousands of animals all in one area, and Motus can pick them all up at the same time. There’s an embedded signature very similar to a Morse code signal that tells you which tag you are recording. If it beeps tut-tut tut-tut, oh that’s tag 511, a northern saw-whet owl. But if it goes beep tuh-tut-tut on the same frequency, that’s a hoary bat down in the valley. And if it goes dit-duh-dit, well, we don’t know what it is, but we can look it up on a website.”

Building Out a Network

While seamless in its ability to track multiple animals, one challenge with Motus is that it requires the construction of stations — lots and lots of stations. And, while hundreds of stations soon peppered the East Coast after Motus’s introduction, much of the rest of the world has remained underserved, including most of the Intermountain West.

ALONGSIDE HIS COLLEAGUE, KATE STONE, BIOLOGIST WILLIAM BLAKE HAS HELPED PIONEER THE USE OF MOTUS TO STUDY ANIMALS AT MPG RANCH AND BEYOND. PHOTOGRAPH BY SNEED B. COLLARD III

This is something scientists at MPG Ranch south of Missoula have set out to rectify with the establishment of the Intermountain West Collaborative Motus Project. Beginning in 2018, Blake and his MPG colleague, Kate Stone, began erecting towers throughout the Bitterroot Valley and into Idaho. By summer 2023, their network included 40 towers, all funded by MPG Ranch at a cost of $5,000 to $15,000 each. The researchers are also working with colleagues in Oregon, Washington, and California to set up additional Motus towers.

Basic Questions, Motus Answers

Many researchers are particularly excited about Motus because it will allow them to answer basic but essential questions that have previously been difficult to answer. These include the size of animals’ home ranges, how and when animals move across the landscape, what they do in the winter, and what places provide critical resting and feeding habitat during migration.

Serendipitously, the rise of Motus has dovetailed with the shrinking of the transmitters. “They have been able to miniaturize Motus tags now to be able to tag butterflies, bumblebees, green darner dragonflies, bats, and hummingbirds,” says Blake. “That’s something we’ve never been able to do before.”

At MPG, three species the researchers are especially interested in are common nighthawks, common poorwills, and Lewis’s woodpeckers. “These are species we’ve gathered a lot of information about already,” Blake says. “We know about their breeding success. We know about their habitat selection. We’re even, in the case of Lewis’s woodpecker, starting to get a better idea of their breeding site fidelity and survival. The big part of the picture that’s missing is to really understand the full cycle of where they go and how their wintering ecology is affecting their populations. And we can’t do that if we don’t know where they go, how they migrate, and how they disperse.”

“So, with Motus, we’re now adding preliminary pieces to how we strategically think of conservation for an animal’s full life cycle, instead of solely focusing on the animal’s breeding grounds. It’s just a new era of bird biology that is slowly emerging and has been almost impossible to grasp until now.”

Night Moves

Tonight, the MPG researchers are trying to catch common nighthawks and common poorwills, two very secretive birds in the nightjar family. Common nighthawks range throughout most of the U.S. and Canada during breeding season, but the birds spend winters in South America. While Motus stations in Brazil and farther south are still few and far between, nighthawk tagging at MPG has already paid off.

“Columbia has been developing an amazing array of Motus stations that have actually picked up a lot of our nighthawks,” Blake says. “One or two stations are in a pinch-point, right where South America really starts expanding from Central America. Scientists there knew that it was a huge migratory route for nighthawks, but in Montana, we didn’t have any idea that our nighthawks were using it.”

Unfortunately, tonight, we have no luck luring nighthawks into the nets, so Blake and his teammates switch the speaker calls to common poorwills — a much easier species to catch. As we sit and stare up at Venus and Jupiter, we hear three poorwills plaintively calling poor-will-ow from three different directions. Suddenly, Blake’s phone lights up with a text from a team member staged at the other net. He glances down and exclaims, “They got one!”

We hurry back to the vehicles, where Scofield and Rolls are gently examining an oddly beautiful bird that resembles a smashed-down owl. While common poorwills are found year-round in the American Southwest and northern Mexico, they show up in Montana only in summer, and little is known about them. One reason is that, like nighthawks, common poorwills sport some of the most perfect camouflage in the bird world.

Blake gets one of the Motus tags ready, a small transmitter with a long trailing antenna that sits like a saddle on a bird’s back and is held in place by two nylon loops that wrap around its legs. Unfortunately, this bird turns out to be a juvenile and the team decides that it might be too risky for it to wear a tag before its feathers have fully developed.

No one is too disappointed, though. Getting to see this remarkable creature up close is a thrill, even for seasoned bird biologists. And the fall tagging season has only just begun. Blake and company still have multiple opportunities to tag poorwills and nighthawks — birds that, thanks to Motus, will continue providing revelations for the scientific world.

Singling Out Songbirds

While MPG stays busy with nightjars, owls, and woodpeckers, scientists from the University of Montana Bird Ecology Lab have spent the last few field seasons at MPG attaching Motus tags to songbirds, such as Western meadowlarks, grasshopper sparrows, lazuli buntings, and, most of all, Swainson’s thrushes.

Motus has especially helped biologists study the movements of hard-to-track songbirds, such as lazuli buntings, that pass through MPG Ranch.

Between 2019 and 2022, they equipped 48 Swainson’s thrushes with Motus tags — with startling results. One thrush leaving the Bitterroot Valley on August 31, 2020, passed through the Florida Panhandle on October 1 and was recorded in Columbia four weeks later. The following spring, it returned to Montana via Costa Rica and, a few months later, was detected in Panama on its return route to its wintering grounds. More than a dozen of the lab’s other Swainson’s thrushes were also detected the year after they were tagged, revealing unprecedented knowledge about the birds’ migration routes and behaviors.

No Comments