03 Aug Ceramics in Montana

If you talk to a dozen ceramic artists throughout Montana, chances are good they’ll cite three reasons for the state’s unique ceramics community: the landscape, the people, and “The Bray.” In a state as vast in area as it is sparse in population, the existence of a rich and vibrant ceramics tradition seems a bit of a miracle. But these three influences hold some irrefutable magic, and the story of Montana clay runs generations deep.

The grounds of the Archie Bray Foundation for the Ceramic Arts alludes to its past as an industrial brickyard, while housing modern facilities for ceramists from around the world. Photographed by Heidi Long

“It’s important that people recognize the treasure that they have in this state, with all of the ceramics going on,” says Josh DeWeese, ceramic artist, professor, and past director of the Archie Bray Foundation, the long-standing arts center that is unarguably the single most influential force in Montana clay. “The Bray phenomenon is central to it because of all the people it’s brought here, combined with the sense of openness — of space and raw potential — that gets under your skin.”

Photographed by Heidi Long

In the late 1940s, a bold, unorthodox plan hatched by four acquaintances began to take shape on the grounds of a commercial brickyard in Helena. Archie Bray, owner of the brickyard, was a civic-minded arts aficionado with a vision for his community. “He was very artistically inclined,” says Steven Lee, another past director of the Bray Foundation. Bray loved classical music, opera, and musical theater, and he would bring actors and musicians to Helena from New York City by train, explains Lee.

Photographed by Heidi Long

A pivotal moment occurred when Bray met Branson Stevenson, an innovative artist and potter from Great Falls, and brothers Peter and Henry “Hank” Meloy, artists from Townsend. “And together they said, ‘How about we build an arts center?’ And ceramics just made sense because the processes and the equipment and the materials were already there,” says Lee.

Frances Senska was a formative figure in launching Montana’s legacy of clay. COURTESY OF THE ARCHIE BRAY FOUNDATION

The Archie Bray Foundation for the Ceramic Arts opened in 1951. A unique admixture of industrial, rural, and urban influences melded at the brickyard and among the friends. “Henry Meloy was a really important artist in the state,” says DeWeese. The modernist painter taught at Columbia University and would come back to Montana in the summers. “His brother, Pete, who wasn’t trained as an artist, would make pots, and Hank would decorate them, and they’d go fire them in the kilns at the brickyard. Everybody from those early days would cite Hank as an important influence,” DeWeese adds.

The brickyard was central to the surrounding community, even in its earliest days. COURTESY OF THE ARCHIE BRAY FOUNDATION

From those nascent years onward — despite the untimely deaths of Hank in 1951 and Bray in 1953 — the brickyard’s circle of influence and inspiration grew. With so few ceramic artists in the state at the time, it became a critical resource and gathering space, as well as a model for what was possible.

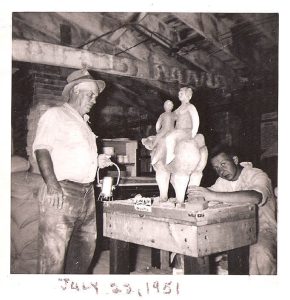

Archie Bray and Rudy Autio are pictured here in July of 1951. Bray’s untimely death would befall him a mere two years later. COURTESY OF THE ARCHIE BRAY FOUNDATION

Another key player emerged on the Montana ceramic scene at this time: Frances Senska. A missionary’s daughter who spent her formative years in the African bush, then returned to the U.S., Senska studied applied arts in college, served as a pilot in World War II, and took a handful of ceramics classes in San Francisco. When she moved to Montana in 1946 and began teaching in the arts department at Montana State College in Bozeman (renamed Montana State University), she brought a unique brand of creativity and resourcefulness. “Senska is really important for her teaching style,” says Lisa Simon, owner and director of Radius Gallery in Missoula. “She brought a set of ideas forward, and those ideas caught fire and changed clay, and the way people thought about clay.”

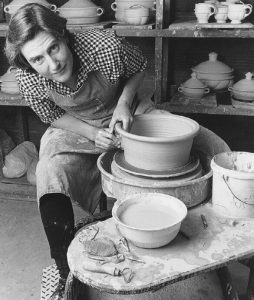

Carol Roorbach served as The Bray’s resident director between 1989 and 1992. COURTESY OF THE ARCHIE BRAY FOUNDATION

Without much formal training in ceramics, Senska built a kiln in the basement of the college’s art building and began honing her craft alongside her students, instilling a sense of experimentation. “She wasn’t just teaching them how to make things; she just really let them loose,” says Simon. “She taught them to work with what you have, follow your instinct, and solve problems. That teaching philosophy was like the genie in the bottle, and she let it out.”

Bray is pictured here shovelling soda into a beehive kiln. COURTESY OF THE ARCHIE BRAY FOUNDATION

Feeding on that curiosity and resourcefulness, Senska and her students tracked down clays in the roadcuts and creeks around Bozeman. “There was a huge interest in local material that continues today,” says Rebecca Harvey, current director of the Bray Foundation. “For me, that’s a throughline all the way back to Senska, digging native clay and throwing it into the back of her new car.”

Senska also brought her students to Bray’s brickyard in Helena, a fortuitous turn of events that arguably shaped the trajectory of ceramic arts in the Northern Rockies. “They have all this clay, because they’re at the brickyard,” says Simon. “That’s one thing Archie gives them: unlimited clay. And so they start thinking, ‘Why go little, when we can go big?’”

Ceramic artist and educator Julia Galloway, pictured here at work in her home studio, found a welcoming and innovative artistic community at The Bray. Photographed by PAMELA DUNN-PARRISH

Among those students thinking big were Peter Voulkos and Rudy Autio, names that are enshrined in the canon of influential ceramic artists. Together, this group pushed the boundaries of clay. Known in turn for their large-scale sculptures and modernist embellishments, Voulkos and Autio reflect Bray’s resources and Senska’s approach, and those influences are evident in the work of many ceramic artists today.

Ceramic designer Casey Zablocki poses with his dog, Ingrid, in front of a selection of his large-scale work. Photographed by KAYLA MCCORMICK

From these beginnings, a remarkable legacy grew. “It would be really interesting to create the family tree of ceramics in Montana,” says David Hiltner, founder and director of the Red Lodge Clay Center. The tree would be massive, intertwined, and flourishing, indeed.

Today, Montana State University and the University of Montana oversee ceramics departments and three major ceramics centers exist in the state — The Bray, the Red Lodge Clay Center, and the Clay Studio of Missoula — all of which offer classes, long-term residencies, and, critically, the opportunity for artists from around the world to live and work in Montana for weeks to years. The result is a community of distinguished artists, with wildly different styles and approaches, coalescing fresh ideas from around the globe.

This inheritance vase by Beth Lo combines ceramic art with a personal narrative relating to her Chinese heritage. COURTESY OF Beth Lo

Unlike many other clay hotspots in the country, which can focus on a specific tradition, Montana has always trended toward freedom and innovation. “When I first came here, I was so stunned by this feeling that anything was possible,” recalls Julia Galloway, ceramic artist and educator. “The overall feel, which is rooted in the centers, is to keep bringing in artists that are pushing. A place that’s rooted in the Bauhaus is constantly looking back, but here there’s this sense of constantly looking forward. What could happen here? Anything could happen here.”

Renowned artist and professor Josh DeWeese was a past director of The Bray. COURTESY OF JOSH DEWEESE

Many Montana ceramists attribute that sense of optimism and freedom to the history of experimentation and the landscape itself. “The wide open spaces and the land have been influential to me,” says Beth Lo, ceramic artist and professor at the University of Montana. “I have heard this from others, too. I think the relative emptiness of the state contributes to a sense of possibility, and it’s easy to feel like we can pioneer new paths.” Casey Zablocki, a Missoula-based ceramic designer whose works were the subject of a solo show in New York City last fall, agrees: “The mountains, the mysteriousness of [the state], the wildness — there’s definitely a huge influence. … I hope you can see Montana in my work.”

This sculptural piece by David Hiltner draws inspiration from the agricultural landscapes of Montana. COURTESY OF DAVID HILTNER

It’s no surprise that Montana’s distant horizons and stunning scenery foster expansive thinking and creativity, but there’s something else, too: an undercurrent or way of thinking that this place engenders. It brings to mind the importance of neighbors in rural communities, the idea that you support those around you, despite distance and differences. “Montana has always been depicted as this place of ferocious independence, which, if you dig deep, is not really true,” says Simon. “But what happened in the clay movement here was giving kind of an independent spirit to the clay artists, to a community of potters who were working together, independently.”

Hiltner is the founder and director of the Red Lodge Clay Center, one of Montana’s three major clay centers. COURTESY OF DAVID HILTNER

This creative freedom and sense of camaraderie is what makes Montana’s ceramics community so unique and remarkably strong. Whether it’s sharing materials and techniques, lending a hand to fire a kiln, or showing up for an opening, “there’s an understanding that we need each other,” says Galloway, who started a membership group called Montana Clay a dozen years ago to help the rapidly growing population of ceramists across the state support one another. “We just needed to see each other once a year, so if there was trouble or you needed anything, it would be so much easier to ask. I had a studio fire, and I was absolutely stunned by the number of people who offered help; people who I only saw once a year.”

The Clay Studio of Missoula fosters community by encouraging novices and highly skilled ceramic artists to craft side by side in a semi-communal workspace. COURTESY OF THE CLAY STUDIO OF MISSOULA

The support within the clay community is wildly enthusiastic, deeply felt, and extended to all, from production potters who have been making pots for 30 years to hobbyists just starting out to world-renowned artists. “Trying to make a living making your work is crazy anywhere,” says DeWeese. “But here, I think there’s a kind of camaraderie and a kind of spirit that people tap into and make a go of it.”

And making a go of it they are. “There are so many ceramic artists in the state now, you can’t keep track of everybody,” says Brandon Reintjes, senior curator at the Missoula Art Museum, adding that Clayworks, a new ceramics gallery in Missoula “[is] like a test kitchen. You walk in and there’s half a dozen artists you’ve never heard of, who are at the top of their craft. They’re either here on a residency, in grad school, or they’ve just been here. It’s really incredible.”

Steven Lee is another former director of The Bray. COURTESY OF STEVEN LEE

The legacy of a wild experiment continues. “I just wonder, what would [Archie Bray] think if he saw The Bray today? He’d probably be floored,” says Lee. The landscape continues to pervade the craft. And artists across the state continue to stretch the limits of clay, bolstered by a community made rich by history and place.

No Comments