24 Nov Winter on the Moon

Gnarled, rugged expanses of black and gray lava rock, dotted with muted green sagebrush, define Craters of the Moon National Monument and Preserve in eastern Idaho during snow-free seasons. Miles before reaching the visitor center, a field of hardened lava appears south of the highway, almost like the shadow of a cloud. But when winter’s soft, white blanket cloaks the landscape, Craters offers an altogether different experience: The lava field gently undulates in sparkling mounds of snow, intermittently pocked by lumpy black rocks.

The Devil’s Orchard Nature Trail is an easy tour, with interpretive signs describing the surprisingly delicate nature of the lava flow. Photo by Henry harrison

Craters is a unique place to explore and an equally superb place to learn, whatever the season may be, though it holds particular intrigue during the winter. Whenever your visit, expect the magic of an out-of-this-world volcanic wonderland.

Formation of Craters of the Moon

The Craters landscape was created by a handful of lava flows over time. The lava here didn’t erupt out of volcanoes, but rather oozed out of fissures in the earth and occasionally spewed forth from vents. Sometimes, a flow partially covered a previous lava bed, other times it created a new one. This lava field is the largest of its kind in the lower 48, offering 618 square miles of cinder cones, lava tubes, tree molds, lava rivers, spatter cones, and lava beds that extend as far as the eye can see.

The 7-Mile loop road allows you to kick and glide past cinder cones, lava hoodoos, and an overall surreal landscape. Photo by Henry Harrison

The first stop for anyone exploring Craters should be the Robert Limbert Visitor Center, where you’ll find maps, as well as the Craters of the Moon Natural History Association bookstore. While the park is always open, the visitor center closes from the end of November through mid- to late-January, after which point the center adopts winter hours and a five-day-a-week schedule. Here, you can wander through the exhibits, get your bearings, and pick up Lunar Ranger packets for any kids in tow.

Though all parks and monuments in the National Park System have Junior Ranger programs, Craters is the only one to have a Lunar Ranger Badge. To earn this accolade, children follow in the footsteps of space explorers, learning about Craters and how the environment helps astronauts train to be in space. As it turns out, the effects of volcanism aren’t just interesting to geologists, biologists, and climatologists; this otherworldly landscape is perfect for NASA research and space mission training. In fact, in 1969, Apollo 14 astronauts prepared for their trip to the moon, also a volcanic landscape, with a visit to Craters. The astronauts learned how to select volcanic samples to bring back to Earth and how to navigate terrain covered by ancient lava. This kind of research continues at Craters today, as astronauts and other space scientists learn about other-worldly environments right here on Earth.

Skiing and snowshoeing at craters

Entrance to Craters is free in winter when the Loop Road is closed to motorized traffic, which is typically between mid- November and mid-April. The Loop Road is groomed for classic and skate skiing as snowfall allows, usually between December and March. Check the park website for current conditions.

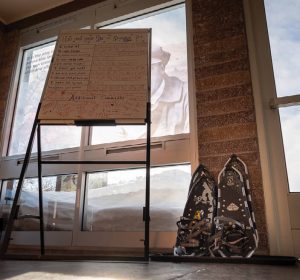

Snowshoes can be rented in the visitor center. Photo by Henry Harrison

The 7-mile Loop Road allows you to kick and glide past cinder cones, lava hoodoos, and an overall surreal landscape. The road is either flat or slightly rolling most of the way, with a big climb and descent around Inferno Cone. Park managers recommend that novice skiers follow the tracks clockwise to avoid the steepest part of the hill on the downhill. It’s a two-way trail, so skiers can turn around at any point if 7 miles is too far.

For a shorter ski, cruise over to the Devil’s Orchard Nature Trail. This half-mile, mostly flat trail skirts through cinder beds. Since the trail is paved, it is a smooth surface to gather snow and makes for easy skiing. Chunks of the North Crater wall may be seen poking through the snow and interpretive panels describe the fragility of the area and the difficulty in protecting it.

To extend your ski tour and cover more terrain, take an offshoot of the Loop Road, past the Lava Cascades, to the Tree Molds Trail. From the signed turnoff on the Loop Road, it is a little more than a mile ski to the Tree Molds Trailhead. The Lava Cascades, if not totally covered in snow, spread out on the left and Big Cinder Cone frames the view as you ski toward the trailhead. The Tree Molds Trail winds past craters, lava flows, shrubs, and limber pines to a series of tree molds, which formed when molten lava flowed around trees. The lasting impressions, from both standing and fallen trees, still contain charcoal from the burning trees, which has been useful for carbon dating the flows. It’s 2 miles round trip to the first group of tree molds; the entire tour, from the Loop Road and back, adds 4 to 5 miles to the trip. The Tree Molds Trail can be a little rocky if there isn’t decent snow cover, but the stretch from the road to the trailhead should make for a nice ski.

A 1-mile snowshoe trail starts at the visitor center, and guided snowshoe walks are usually offered some Saturdays in January and February. Photo by Glenn Oakley

Those seeking a bit more adventure may enjoy carving some turns on Inferno Cone, just off the Loop Road. This open slope is great for telemarking, as are many other cinder cones along the Loop Road.

Snowshoers can stay to the side of the ski tracks, walk the 1-mile Snowshoe Loop Trail starting at the visitor center (follow the orange snow poles), or venture off of the trail and explore wherever there is enough snow. Intrepid snowshoers can climb a cinder cone, wander among limber pines, or explore a cinder bed. Additionally, organized snowshoe walks are usually scheduled on Saturdays in January and February, and no prior snowshoe experience is required.

Check the calendar on the park website for a schedule of all programs and pick up snowshoe rentals at the visitor center. If you want to ski, you will need to bring your own, and remember to leave the dog and bike at home; neither is allowed on Craters’ snow-covered roads.

Whether you are skiing or snowshoeing, be prepared for winter conditions. A bluebird day can quickly turn into a storm, and brisk winds are the norm even on warm, sunny days. As with any winter outing, carry extra clothing, water, and a snack. Know your own abilities and do not ski so far that you become exhausted. Use caution if you leave the groomed track; the surface of the lava beneath the snow is very uneven and a blanket of powder may conceal cracks and sharp rocks.

visit atomic city

Craters is about as remote as it gets; the small town of Arco is 20 miles northeast, and Idaho Falls and Twin Falls are each about 90 miles away (to the east and southwest, respectively). There are a couple of gas stations and restaurants in Arco, but for anything else, stock up before you leave your starting destination.

The ski trails at Craters offer skiers and snowshoers of all experience levels a chance to explore the volcanic landscape in a unique way. Photo by Henry Harrison

Arco is a fascinating town for its roadside attractions. According to a large marquee in town, Arco was the “first city in the world to be lit by Atomic power.” In July 1955, the town was powered for about an hour by Argonne National Laboratory’s BORAX-III reactor.

Another oddity found in Arco is the Devil Boat. Known as the “Submarine in the Desert,” the Devil Boat seems to rise from the ground in a small city park. It’s actually the sail of the USS Hawksbill, with the number 666 painted on the side. (Apparently, any connection with the occult is coincidental.) The submarine was placed in Arco — far from any ocean — to honor the city’s long association with the Navy nuclear fleet.

Across the street from the submarine is Arco’s must-try restaurant: Pickle’s Place, a diner serving fried pickles and pickle popsicles, in addition to a solid selection of burgers and other American diner food.

No Comments