28 Sep Artist of the West: Chords of Color

In Robert Moore’s paintings, colors and shapes work in concert to make even the most familiar facets of the world look fresh. Aspen trees, garden hollyhocks, cattle standing on an expanse of sunlit grass — none of these are novel sights, especially to those who live in the West. But on Moore’s canvases, they radiate not only profound beauty, but singularity: a grove of aspens composed of inimitable individual trees, not one of them interchangeable with the others. To experience Moore’s art is to be reawakened to the breathtaking diversity of life on Earth.

WINTER TIDE | oil on canvas | 48 x 48 inches

Moore has been attentive to the nuances of the natural world since he was “a child growing up along the banks of the Snake River, just running up and down,” he says. “My love for nature, it’s always been there.” A native of southern Idaho, where he still makes his home, Moore attributes this love, in part, to the pleasure of living in a place where fertile farmlands, arid desert landscapes, and alpine forests coexist in close proximity. “The variety in our country,” he says, is immense, noting the juxtaposition of fragrant sagebrush with cold mountain lakes. “It goes from 3,000 feet in elevation all the way up to over 10,300 feet.” I appreciate and love those differences. And, when I’m designing my paintings and looking at nature, I’m always looking for the differences that give something its character: What makes that cloud shape the only cloud that will ever look like that, have that character? And yet, even a mile down the road, that cloud has a different character to it, different traits.”

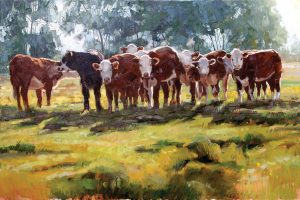

MORNING CATTLE | oil on canvas | 40 x 60 inches

Moore’s contemplative sensitivity to the wondrous variety of forms within nature is deeply tied to his spirituality. “E pluribus unum,” he says, before translating the Latin phrase: “Out of many, one.” For Moore, this expression points to a fundamental unity, or oneness, from which all the subjects of his paintings derive, and in which they all coexist. “It’s a universal desire or challenge for a representational artist to try to balance unity with diversity, to find harmonies in variety,” he says. “Everywhere I’ve painted, I’ve seen this as the signature of God: the perfect use of harmonies within a unity. There’s that order, that unity, on the one hand, and that variety, that diversity, on the other hand. I’m trying to capture that balance.”

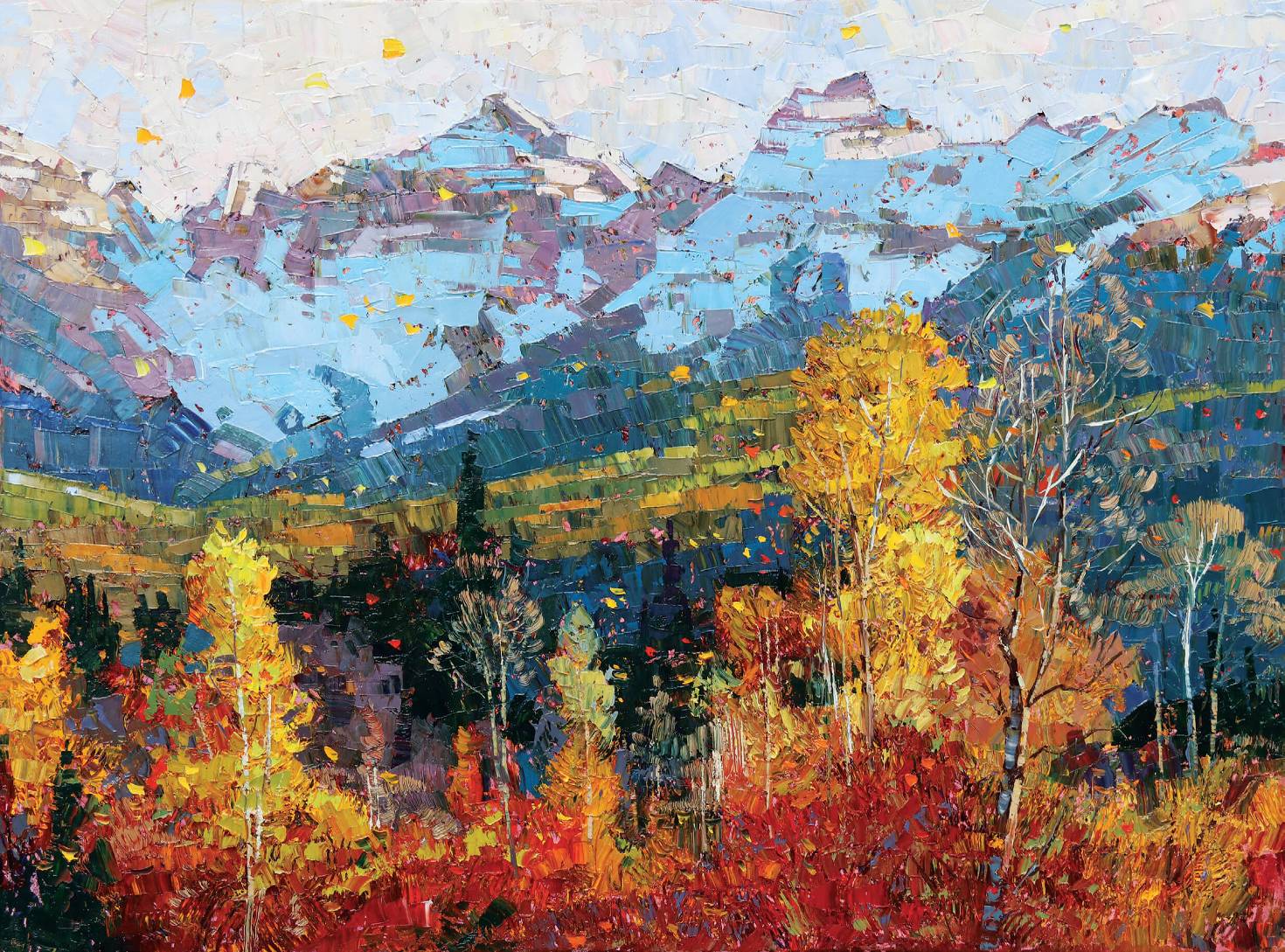

WELL WITH MY SOUL | oil on canvas | 70 x 96 inches

Moore enjoys painting outdoors. A father of eight, he spent countless hours outside with one of his infants strapped to his back, while he transformed his surroundings into works of art. These days, the 65-year-old often paints from photographs in his studio, where four of his grown children have worked as his helpers over the years. The ambidextrous Moore creates his wonderfully textured, impressionistic works with both hands at the same time. “As I dirty a pair of brushes or a pair of knives, I throw them down and pick up a clean set,” he explains. “My helper keeps the tools clean and ready for me to pick up without stopping my painting process.” He also relies on a helper to keep the paints arranged in specific positions on his palette, because Moore identifies the oils by their location. Surprisingly, the artist who makes such vividly hued paintings is actually colorblind. “When I see a rainbow,” Moore explains, “I see yellow and blue. I cannot distinguish the reds and greens and violets and blue-greens.”

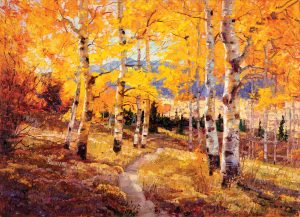

WINTER EXTOLMENT | oil on canvas | 48 x 48 inches

As a young painter, Moore struggled with his colorblindness. Over time, he became adept at painting his perceptions, and what may have been an unfortunate physical quirk became an asset. Color is a defining characteristic of his work. Sumptuous, kaleidoscopic, and celebratory, Moore’s colors simultaneously seem to take on new life, and make life itself feel new.

In Winter’s Extolment, warm flecks of gold and orange — the lingering autumnal leaves that cling to aspen trees in wintertime — hang from branches above the snow-covered ground. In places shadowed by tree trunks, the snow is rendered in wonderfully icy blue hues. The trunks themselves bare shades of wine, black, brown, and blue. In the distance, hints of deep vermilion seem to rise from the earth, evoking an essential vitality that persists even through the coldest time of year. Both unexpected and revelatory, these colors work in tandem with the painting’s shapes and lines to produce an effect that’s nothing short of sublime.

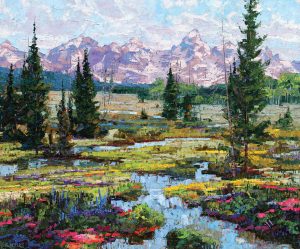

LOVELY ON THE MOUNTAINS | oil on canvas | 60 x 72 inches

“I am amazed by the precision of his lines and edges and the precise application of color,” says Mark Tarrant, who features Moore’s work at his Jackson Hole gallery, Altamira Fine Art. “This produces a picture of overwhelming beauty and emotion. I look at paintings for the overall impact and quickly assess, ‘Did the artist accomplish what he set out to do?’ and Moore does. He is a master at this. You intuitively feel his confidence in handling paint.”

This confidence comes, in part, from Moore’s unique understanding of color. To his eye, just as there is unity and harmony in the immense diversity of natural phenomena on Earth, there’s an order and harmony in the values of colors, even those he does not see as others do. “The colors that I see are chords of color, not just single notes,” he says, using a musical term that befits his harmonious vision. “They’re chords of related color, and that’s what is beautiful to me.”

POPPIES | oil on canvas | 48 x 24 inches

Rose DeMaris writes poems, novels, and essays. Her fiction and nonfiction have been published by Random House, The Millions, and Big Sky Journal. Her poetry has appeared in Alaska Quarterly Review, The Los Angeles Review, The Fourth River, Roanoke Review, Pine Row Press, Cold Mountain Review, and elsewhere. A California native, she lived, hiked, and taught in Montana for nearly 20 years, and now calls New York City home; rosedemaris.com.

No Comments