03 Feb Casting from the Shoulders of a Giant

In 1960, 34-year-old Joan Cummings — later to become Joan Wulff — used a one-handed bamboo fly rod to cast 161 feet and set an unofficial women’s record. Unofficial because there was no women’s distance division in casting events at the time; Joan competed with the men.

In 2018, 14-year-old Maxine McCormick used a graphite rod to cast 161 feet in a similar one-handed event, matching Joan’s distance. This time, McCormick set an official women’s record at the World Championship of Flycasting and followed that up with a 189-foot cast in the two-handed distance event, another one of the six women’s events.

Although the distance of McCormick’s record-setting cast was the same as Joan’s, competitive casting and fly fishing had undergone a sea change in the intervening six decades. “The arc of Joan’s life perfectly encompasses the development of modern fly fishing,” says Tom Pero, fishing writer and long-time friend of Joan’s, “from her graceful tournament casting with heavy bamboo rods and high-maintenance silk lines during the 1940s, to her flawless teaching with ultralight graphite rods and synthetic lines into the 2000s.”

The First Lady of Fly Fishing, as she is known, has both witnessed and helped bring about changes in fishing tackle and gear, along with influencing the popularity, demographics, and conservation ethos of the sport. Over her life and career, Joan Wulff, now 95, built a strong foundation for fly fishers, both women and men.

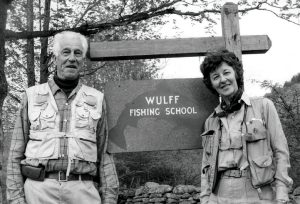

In 1979, Lee and Joan Wulff started the Wulff School of Fly Fishing, based in Livingston Manor, New York. | JOAN WULFF/THE WULFF PROJECTS

Born in 1926 in New Jersey, Joan grew up in a time when women didn’t question the fact that their brothers would go to college, while they would marry and raise a family. But young Joan did question why her father had skipped over her and taught only her younger brothers to shoot and cast. At 10, she convinced him to let her join the Paterson Casting Club, and she went on to win her first state championship in 1938.

Around the same time that she began casting, Joan also started taking dance lessons and was soon teaching classes herself. In a 2016 interview, Joan named Eleanor Egg, owner of the dance school and a world-class track-and-field athlete from Paterson, as an early mentor.

In 1943, at age 16, Joan won her first national casting accuracy championship, one of the two categories in competitive casting. Along the way, she questioned why her casting instructor wanted her to use only her wrist and not lift her elbow, noting that when she raised her arm, she could cast farther. Joan went on to win one international and 16 national titles by 1960 — using her whole arm. Her whole body, in fact. In a 2018 interview, she said, “I loved that casting was whole-body, you had to use every part of your body, from your fingertips to your toes.”

Joan casts in a tournament in Peoria, Illinois in 1960. Over her career, she won one international and 16 national casting titles. | JOAN WULFF/THE WULFF PROJECTS

Joan attended secretarial school and then worked in New York City while continuing to teach dance classes on Saturdays. But the success of the dance school saved Joan from a desk job, and when she was almost 18, she started teaching full-time as Egg’s partner. The school thrived and supported Joan’s love of travel and competitive casting. In 1947, she and her mother drove from New Jersey to a national tournament in Long Beach, California. This was before many roads were paved in the West and long before interstate highways. That year, Joan cast 120 feet in her first national distance event. Distance events are the second category in competitive casting. Accuracy events test skills in putting flies right where the fish are, and distance events test skills in reaching the farthest fish.

Joan trained with William Taylor, an angler who also cast with his whole arm and made his own rods. When Joan found his rod too heavy, Taylor built her a lighter one. Once she had the right rod, Joan could compete with the men in distance events. This was her only option, as there weren’t enough women competing to hold separate male and female events. In 1951, she beat an all-male field — including her then-boyfriend — to win the National Fisherman’s Distance Fly Championship.

In a 2018 interview, Joan described waking up one day in 1952 and realizing, “If I don’t get out, I’ll be happily teaching dance at 75.” She walked away from the well-paying job to see if she could make a living in the fishing world. She didn’t labor over the decision or second guess herself; she knew it was the right move.

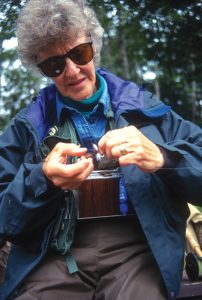

Joan readies a Royal Wulff, a legendary fly designed by her husband Lee Wulff. | Photo by Tom Pero

Joan hit the sportsman’s show circuit and traveled more than ever. She wowed audiences as a trick caster, taking cigarettes out of people’s mouths and slicing bananas. While she usually performed in shorts, a creel, and rolled-down hip boots, one emcee asked her to wear an evening gown and high heels. “There was no trick casting, but the audience responded to the grace and beauty of casting,” Joan said.

In 1958, Joan became the first woman to have a paying contract in the fishing industry when she started working for the Garcia Tackle Company. By then, as a wife and mother, she visited tackle shops part-time while continuing to win casting championships and set records.

Joan met Lee Wulff when she appeared on the American Sportsman television show in 1966. Although they were both married at the time, she fell in love with Lee as decisively as she had left her job at the dancing school. They married in 1967.

Lee was a fly fisherman, filmmaker, pilot, thinker, tinkerer, and inventor. He sewed the first fly-fishing vest in the early 1930s, invented the still-popular Royal Wulff dry fly — in addition to many others — and developed specialty fly lines and rods. The couple founded Royal Wulff Products in 1983. Run today by Doug Cummings, one of Joan’s two sons from her first marriage, the company carries many of Lee’s innovations.

As “America’s fly-fishing couple,” the Wulffs traveled to workshops and dinners at fishing clubs and conservation groups across the country. Lee showed his films about Atlantic salmon fishing in eastern Canada, shared clips from his television shows, and talked about conservation. Known as the “father of catch-and-release angling,” Lee was the first person to bring this issue to light in 1939, when, in Lee Wulff’s Handbook of Freshwater Fishing, he wrote, “A good game fish is too valuable to be caught only once.”

But, as Pero remembers, “Joan always stole the show. She spoke clearly and directly to everyone in the room, demonstrating how easy it is to cast a fly. Men paid attention and, so, in increasing numbers, did their wives and girlfriends. And every woman — young or old — who picks up a fly rod today has a little bit of Joan Wulff in her first cast.”

Joan tap-dances in a 1951 recital for the dance school where she was a partner and instructor. | JOAN WULFF/THE WULFF PROJECTS

As more females started fly fishing, women’s gear improved. A decades-old photo caught Joan in mid-air, clicking her heels together in a pair of lightweight waders. She was jumping for joy because lightweight waders became available in the 1970s, and the new models “made such a difference to women’s fishing life,” she said in 2018. “And now, with the upsurge of women coming into fly fishing, companies like Orvis and Patagonia are actually making gear and clothing for women. We’ve never had that before.”

Terry Myers and her husband, Jerry, have spent decades guiding and fishing in Idaho’s Salmon River wilderness. While Terry agrees that women’s gear has improved over her career, she points out that there’s still room for advancement. “I row a boat all day on a wet, sandy boat box,” she says. “I’m in the wilderness, setting up camp in ice-cold weather. I need heavy waders. To this day, I wear small men’s steelhead waders and men’s wading boots. They’re kind of like walking around on cinder blocks, but they’re the only ones tough enough to work and wade in this rugged country.”

Joan demonstrates fly casting in the Philadelphia area in the early 1980s. Here, she’s joined by hotelier Charles Ritz (second from left), who was a friend and fan of Joan’s, and her husband Lee (third from left). | JOAN WULFF/THE WULFF PROJECTS

Women are typically smaller and have less muscle mass than men. As a result, Joan said in 2016, “The one big reason there are so few women of my generation in fly fishing is because of the tackle. It was damned heavy, and the grips could be more than an inch in diameter. So, you’d try, and your hand would hurt, and you’d say, ‘I’m going to read a book.’” Instead, during a 16-year collaboration with the R.L. Winston Rod Company in Twin Bridges, Montana, she developed “Joan Wulff’s Favorite” rods. Lightweight and responsive, with a smaller-diameter grip, these rods work well for women and other smaller humans.

Joan often says that she’s a teacher first. In 1979, she and Lee opened the Wulff School of Fly Fishing in the Catskills region of New York. After Lee died piloting his airplane in 1991, Joan continued to teach at the school, which her son Doug now manages.

Along with teaching casting, Joan strives to teach the importance of caring for fish and their habitats. Active with Trout Unlimited, the Atlantic Salmon Federation, and many other fish conservation groups for decades, she has made contributions that have been recognized by countless angling organizations. Joan and Lee’s lives and legacies have been documented in two recent (but still unreleased) films as well.

Joan performed at sportsman’s shows in the 1950s, usually wearing fishing gear and trick-casting. But in St. Louis in 1954, the silent movie star Monte Blue (right) suggested formal wear and a show focusing on the grace and beauty of casting. | JOAN WULFF/THE WULFF PROJECTS

Joan is often credited with bringing women into the sport of fly fishing, but she argues that Robert Redford’s 1992 film “A River Runs Through It,” based on the novel by Norman Maclean, was responsible. “He had the beautiful places we like to fish, the beautiful, mesmerizing loops unrolling — and all the attractive men I used to have all to myself,” she said in 2016. “For the 12 years after the film, we had more women than men at the school.”

Alice Owsley, owner of Riverside Anglers in West Yellowstone, Montana and a fishing guide for more than 20 years, attended the Wulff School in 1999. She took Joan’s Instructors Course because she believes that casting instruction is the most essential element she can provide her clients. Owsley’s time at the school was memorable, and she recalls that there’s “so much value for the time you spend there. It’s intense. The material is very reflective of what you should be providing as an instructor.” She adds that Joan is “very strict about the fundamentals of casting; her casting style works in a bunch of different places. And Joan’s the quintessential professional in her presentation.”

This Medal of Honor was awarded to Joan by the Anglers’ Club of New York in 2018. She was the 11th person and the first female to receive the award in the club’s 112-year history. | JOAN WULFF/THE WULFF PROJECTS

Before she attended the Wulff School, Owsley had already studied Joan’s 1987 book, Fly Casting Techniques, the first to break down the mechanics of casting into three fundamental parts, and to develop a vocabulary to precisely explain each one. The book included drawings — instead of “photos of men in khaki” — to illustrate the techniques. Joan went on to write three more books, make an instructional video, and update Fly Casting Techniques. She also wrote a bi-monthly column in Fly Rod and Reel magazine for 22 years, along with numerous articles in other magazines on topics such as, “Do competitive casters go fishing?”

Owsley knows something about that question: She competed in her first casting event in San Francisco in October 2021. “I could relate a lot of things in the tournament to fishing scenarios,” she says. “In one I realized, ‘This isn’t any different from fishing for rising fish on a lake, where the fish are moving and the water isn’t.’ It was super fun.”

Joan was recently interviewed for a yet-to-be-released documentary about her life and career. | JOAN WULFF/THE WULFF PROJECTS

Despite women’s gains in the sport, Owsley says that she still doesn’t see many female guides at the boat ramp. “It’s changing, and there are plenty of female clients, but I’m still sometimes the only female guide,” she remarks. “I think we still have challenges ahead of us. It’s great that there are so many more women fishing, but there aren’t a lot of women in the industry of Joan’s caliber.”

In a recent phone interview, Joan responded, “I had to live a long life to see women coming into the sport, but they’re in it now, and they love it as much as men do. It’s going to be alright because of women’s inherent strength and talent. Women are coming into the sport and men are welcoming them.”

Mary Thompson

Posted at 03:39h, 24 AugustInteresting that you think the biggest difference between Maxine and Joan’s 161ft casts was the rods used. The biggest difference was actually the lines used. Maxine used a floating shooting head weighing less than 25 grams. Joan used a high density shooting head weighing close to 38 grams. Even Joan would agree that casting a lighter floating shooting head 161ft is a much more difficult feat. In fact, casters today routinely cast high density 38gram line over 200ft.