23 Nov History: The Grand Master of Portraiture

In 1832, at the age of 23, Swiss painter Karl Bodmer was commissioned by naturalist, ethnographer, and explorer Prince Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied to create a pictorial record of what would later be known as one of the most important ethnographic expeditions in North America during the 19th century. Although he had no previous training in portraiture, Bodmer captured the visages and regalia of the Indigenous people he encountered in the Upper Missouri region with photographic-like detail.

PÉHRISKA-RÚHPA, MOENNITARRI WARRIOR IN THE COSTUME OF THE DOG DANCE | Karl Bodmer | March 1834

As historian William H. Goetzmann observed, “No other painter of the American Indian came close to the ethnographic accuracy that Bodmer achieved in [his depiction of] clothing, ornamentation, body marking, accouterments, and ceremonial paraphernalia.” Bodmer also documented the different landscapes the expedition traveled through, ultimately producing almost 400 watercolors and sketches, 81 of which were published in aquatint for the 1843 English edition of the prince’s book Travels in the Interior of North America.

During his visit to Montana, Bodmer created portraits of Assiniboine, Gros Ventre (Atsina), and Blackfeet Tribal members. However, some of his finest works were rendered at Fort Clark, where the expedition stayed from November 8, 1833, until April 18, 1834. And while his Mandan and Hidatsa portraits are extraordinary, to gain a true appreciation of their quality, one must take into consideration the circumstances under which they were created.

That winter was bitterly cold, even by Upper Missouri standards. Maximilian’s journal entry for January 9, 1834, indicates that the temperature at 8 a.m. was 20 degrees below zero, and under such conditions, “brushes and colors freeze while painting, [so] we had to keep warm water always [available].” On January 30, 1834, Maximilian noted that the thermometer registered 45 degrees below zero for more than 14 days.

Despite these challenges, the winter of 1833-1834 was by far the most productive phase of the expedition. Maximilian’s ethnographic research and the pictorial record that Bodmer compiled during their stay at Fort Clark were also timely: Although mortality estimates vary significantly, approximately 90 percent of Mandans later perished during the smallpox epidemic of 1837-1838.

One of the images that illustrates the artist’s virtuosity is Bodmer’s full-length portrait of Mató-Tópe (“Four Bears”), one of the most iconic Plains Tribal members of the early 19th century. For the occasion, the Mandan chief was clad in an ermine- and hair-fringed shirt made from bighorn sheepskin and an ermine-fringed, split-horn bonnet with a full-length trailer of eagle feathers. Three-row quillwork, which is visible on one legging strip and the shoulder strips of his shirt, was typical of Upper Missouri-style quill embroidery from the 1830s and 1840s.

According to Maximilian, Mató-Tópe was the only Mandan of that era who was entitled to wear the split-horn bonnet, which signified preeminent status. The blood-stained lance that the chief is holding originally belonged to an Arikara warrior who used it to kill Mató-Tópe’s brother. After waiting four years to exact his revenge, Mató-Tópe traveled on foot alone for nearly 200 miles before reaching the enemy village. As night fell, he entered the lodge of his Arikara adversary, where he ate a leisurely meal and then smoked the owner’s pipe before slaying him with his own lance and taking his scalp. Based on an account that Mató-Tópe gave to painter George Catlin, that scalp is also depicted in Bodmer’s portrait.

PÉHRISKA-RÚHPA, A MINATARRE OR GROS VENTRE INDIAN[HIDATSA] | Karl Bodmer | 1834

Bodmer’s other portrait of Péhriska-Rúhpa features the leader in all of his finery, the centerpiece being an ermine- and hair-fringed shirt embellished with a background of bright-yellow quillwork. Its visible shoulder strip exhibits the signature trait of plaited quillwork, a craftworking technique then associated with Crow artisans. This embroidery method produced an intricate matrix of tiny diamonds, with design compositions formed by quills of contrasting color. And in addition to a grizzly bear claw necklace, Péhriska-Rúhpa wears quilled leggings and moccasins that are covered in blue and white “pony” beads (named after the pony pack trains of the 17th-century traders who delivered beads to the Plains Tribes). The color scheme — noted by Lewis and Clark — reflects those preferred by Northern Plains Tribes at that time.

Péhriska-Rúhpa’s buffalo robe is emblazoned with an elaborate version of the feathered-circle motif, a pattern commonly employed by Siouan peoples to decorate men’s robes. The use of only red and black paint for this design illustrates the limited palette available to Plains Tribal painters before commercial pigments became widely accessible.

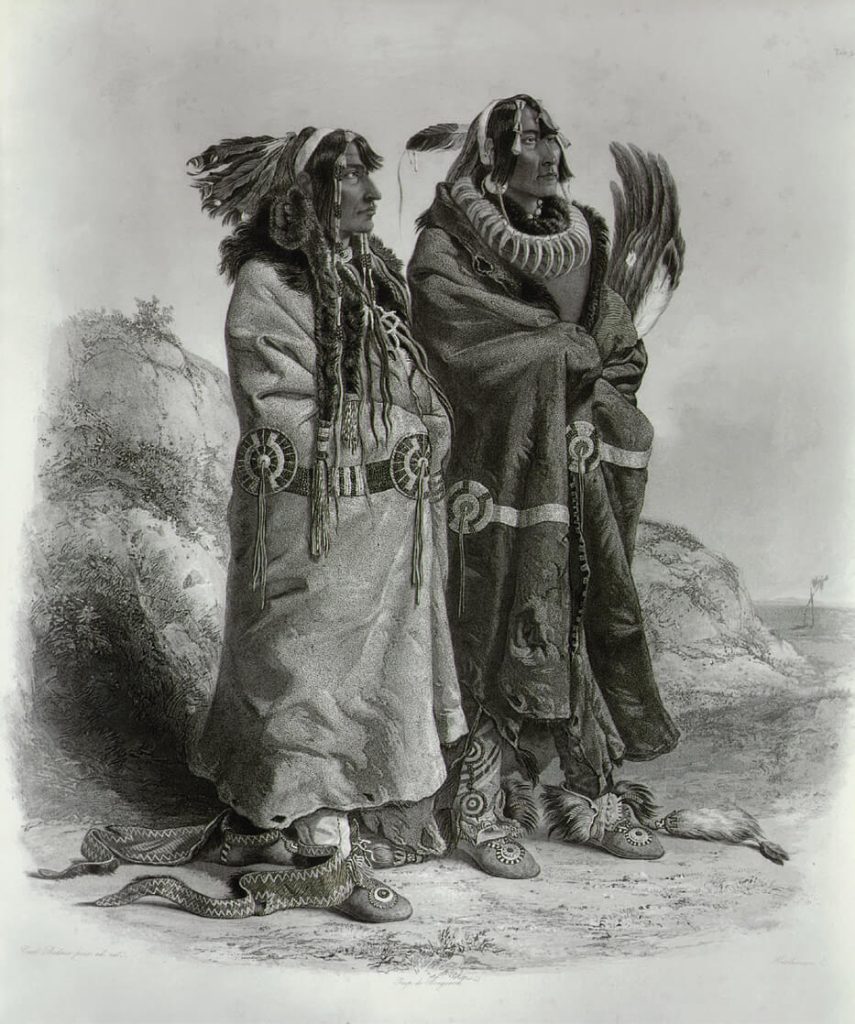

Another fine portrait by Bodmer features two Mandans, Sih-Chidä (“Yellow Feather”) and Mahchsi-Karehde (“Flying War Eagle”), wearing buffalo robes with strips composed exclusively of blue and white pony beads. The wavy vertical rows of white beads on the strip that adorns Sih-Chidä’s robe are an example of the Crow-Stitch, a technique that was used to more closely define traditional patterns.

The centerpiece of Mahchsi-Karehde’s regalia is a grizzly bear claw necklace that’s attached to a strip of otter skin, with blue spacer beads interspersed between the claws. Given the obvious danger associated with procuring the weaponry of grizzly bears, the Plains Tribes exercised discerning taste in their selection of claws. According to Maximilian, they preferred those taken in the spring, when they’re “frequently three inches long.” At that time, he continues, the tips of bear claws are “tinged of a white colour, which is much esteemed.” Only a grizzly’s front claws were used for necklaces.

SIH-CHIDÄ & MAHCHSI-KAREHDE, MANDAN INDIANS | Karl Bodmer | December 1833

If there is one stylistic attribute that characterizes Bodmer’s work, it’s his painstaking attention to detail. That quality is readily evident to casual observers, but these images should not be interpreted as photographic snapshots in time. Surviving sketches indicate that published aquatints are the final product of a process similar to editorial revisions often made to successive drafts of a written manuscript. To accomplish this goal, Bodmer kept his own journals, where he meticulously recorded observations pertaining to Plains Tribal regalia. Bodmer ultimately produced an unsurpassed pictorial record of the lives and material culture of the Plains Tribes during a period when accurate ethnographic data was, at best, fragmentary.

Based in Billings, Montana, Doug Schmittou writes about travel in the Northern Rockies; evidence-based wellness protocols; and 19th-century Plains Indian art, material culture, and ethnohistory. His work has also appeared in Montana: The Magazine of Western History, Plains Anthropologist, and American Indian Quarterly.

No Comments