23 Nov Christmas Eve 1920

Long George Francis was becoming more frustrated by the minute as the narrow tires of his 1914 Hupmobile slid uncontrollably in the mix of icy clay gumbo and snow. The steering wheel turned effortlessly in his big hands with little effect on the car’s direction of travel. He wished he was aboard his horse, Tony, rather than fighting the mounting blizzard in such a faulty, man-made conveyance. He berated himself as he thought of the crate of apples and boxes of candy resting in the back seat. The treats for the schoolchildren sat next to presents for Amanda. His desire to visit Amanda one last time before going to prison, and his impulse to play Santa Claus for her students, had placed him in great jeopardy.

It was Christmas Eve 1920 and, as daylight faded and temperatures plunged, George was in deeper trouble than he’d ever imagined. When he left Havre earlier in the day, it was cold and had just started snowing. Now, his surroundings were featureless. There was no discerning where the gray, snow-filled sky and the flat prairie met. No contrast existed, except for an occasional glimpse of the icy Milk River and the skeletons of cottonwood trees here and there. As the parallel ruts across the barren miles became obscured by snow, he had only the riverbank to guide him toward the high plains schoolhouse in Simpson and its entire faculty: Amanda Speer.

The wind had risen to such a pitch that he could no longer hear the engine’s pops and gurgles. A sheet of ice over the windshield, plus blowing snow, totally obscured what lay ahead, and the side curtains blocked any lateral views. Opening them to stick his head out only resulted in sleet filling his already teary eyes. Out of nowhere, a snowdrift appeared before him and, backing up, he felt the world tip sideways as the car rolled off the cut bank and into the Milk River.

Already cold, he was shocked by the icy water as the car landed upside down, partially breaking through the frozen river. Frantically, he grabbed at cracks in the ice and the collapsed roof frame, trying to pull himself out from under the car. His right leg throbbed with pain, stuck in a vise between the ice and the car’s roof. He pulled again with great effort and finally freed himself.

George crawled to the unbroken surface nearby and gasped for air. Then, fear quickly replaced frustration; it was at least 5 miles to the nearest help. The mounting blizzard, broken leg, and wet clothing made the task seem insurmountable. The car — still upside down on the frozen river — was useless, and again he cursed his poor choice of transportation. His horse, Tony, would have gotten him through, he thought, even in his condition; the 20-horsepower Hupmobile was no substitute for the one-horsepower horse.

The blizzard gained intensity, and George guessed the temperature had fallen to at least 20 below. He tried to stand but could bear no weight on his fractured right lower leg. He pulled himself up the steep frozen bank by digging his fingers into the ice and mud. At the top, he lay exhausted, trying to take stock of his situation. Survival would require splinting his leg before he made any attempt to travel. Realizing he had to salvage anything useful from the wrecked car, he reluctantly slid back down the bank.

The splintered apple crate and a flashlight were both resting at the river’s edge, where they landed as the car rolled. In the dim beam of his flashlight, George saw the sharp end of his tibia protruding through the skin about midway between his knee and ankle. He thought about the horseback riding accident he experienced many years ago and laughed grimly. He’d broken his leg in the exact same spot. Perhaps he could make a splint with the apple box slats and bind them to his leg with strips from the blanket that was wrapped around the other gifts; this might allow him to bear weight. The cloth strips, if tight, might also act as a tourniquet, as blood was now flowing briskly from the wound.

Crawling back up the bank with supplies, George wondered where his pistol was; probably in the half-submerged Hupmobile, he thought, and no one would hear a shot in the howling wind anyhow. Due to conflicts and confrontations with others, he now traveled with a gun. A recent shootout with a notorious bootlegger, along with a false conviction for horse theft, made him justifiably paranoid. The absence of his pistol now contributed to his sense of dread.

George’s hands were freezing in his wet gloves and would be poor tools for fashioning a splint. Their pain nearly equaled that of his leg, and he would need to work fast and get moving before hypothermia set in. He tried two unbroken slats from the apple box for length, placing one on each side of his leg from knee to ankle. He cut strips from the blanket with his pocket knife and tied the makeshift splint as tightly as his freezing hands could manage.

Shaking violently and feeling light-headed, George was able to briefly bear some weight on the leg, although it was with great pain. Calculating his location, he thought there might be a dugout shelter about half a mile away. The nearest ranch house was at least 5 miles away, which, in his condition, might as well have been 1,000. Forcing his body to move, he hobbled along until he fell. Then he crawled. What little strength he had was fading fast, and it was getting harder to think clearly. The pain in his leg was subsiding, and he knew that wasn’t a good sign.

The flashlight fell from George’s numb hands. It hadn’t helped much in the blinding snow, anyway. He was about halfway to the dugout he figured, but the effort became overwhelming. As he lay still on the snowy ground, he was about to give up when he suddenly saw flashing lights behind him. Were these new lights approaching or had the Hupmobile lights still been on after the wreck? He couldn’t remember. Maybe his luck was about to change, but he didn’t much care. He felt warmer now, almost comfortable.

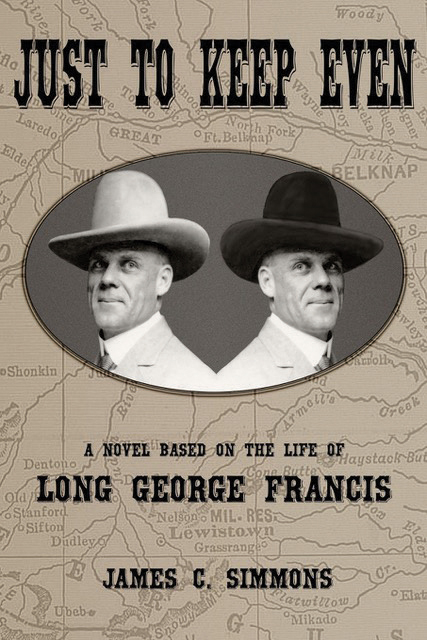

Excerpted from Just to Keep Even, a forthcoming historical fiction novel by James C. Simmons about Long George Francis, the most infamous individual in Hill County, Montana at the dawn of the 20th century. During a time when cattle rustling, gunfights, underground brothels, illicit moonshine, and other shady dealings were at an all-time high, Francis played both sides of the fence. The product of a strict Mormon upbringing, he was a gentleman who didn’t swear or drink, and also a cattle rustler and accused horse thief. Known by many notables of that era, Francis was featured in pen-and-ink cartoons by artist C.M. Russell. His early years on Montana’s Hi-Line were informed by the ethos of the open range, and, in adulthood, his cowboy skills helped him become a top-notch rodeo showman who was eventually inducted into the Montana Cowboy Hall of Fame.

Excerpted from Just to Keep Even, a forthcoming historical fiction novel by James C. Simmons about Long George Francis, the most infamous individual in Hill County, Montana at the dawn of the 20th century. During a time when cattle rustling, gunfights, underground brothels, illicit moonshine, and other shady dealings were at an all-time high, Francis played both sides of the fence. The product of a strict Mormon upbringing, he was a gentleman who didn’t swear or drink, and also a cattle rustler and accused horse thief. Known by many notables of that era, Francis was featured in pen-and-ink cartoons by artist C.M. Russell. His early years on Montana’s Hi-Line were informed by the ethos of the open range, and, in adulthood, his cowboy skills helped him become a top-notch rodeo showman who was eventually inducted into the Montana Cowboy Hall of Fame.

To this day, Francis’ death remains a mystery. Did he die in a blizzard after his car crashed? Or was he murdered? In his book, Simmons offers a plausible end-of-life story that also spotlights a fascinating period in the history of the West.

No Comments