09 Aug Outside: To Write a River

I came to the river to write: not a fishing story exaggerating about a trout the size of a fat dachshund, but to capture the very soul of the river. But I couldn’t.

It was strange to acknowledge that realization, considering that I grew up around water. As a boy, I lived within walking distance of Rattlesnake Creek, a tributary of the Clark Fork River that wound its way through my hometown of Missoula, Montana. That’s where I cut my teeth, wading in high-top Chuck Taylors and chasing trout with a cheap rod and reel, a Band-Aid can full of worms, and a packet of Eagle Claw hooks. And that’s also where I fell in love, not with a pretty girl, but with the water.

When I grew older and got my driver’s license, my torrid affair with water blew up like a Montana thunderstorm. All the classic rivers around Missoula became fair game. The Bitterroot, Clark Fork, Blackfoot, and an abundance of small creeks were subject to my mad pursuit of trout. And my new tactic for catching this wily creature was with a fly rod.

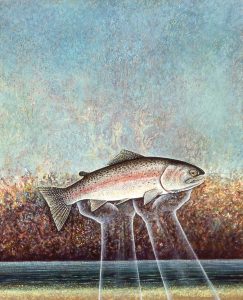

As I sat near the river, unable to find the right words, I defaulted to reliving some of my earliest memories associated with water. There was a scary encounter with a moose in a brushy river bottom, there were days when I seemed to attract birds and bats more than fish, and there was the time I hooked a splashy rainbow on Rock Creek only to have a large bull trout try to steal my prize. But the one that stands out the most was an indelible experience on the Blackfoot.

That day, I’d driven my dad’s ‘69 F-150 to the river and hiked a good ways upstream looking for a promising spot to fish. Ahead, a large flat stone stuck out of the current. It was the perfect place to freely cast, and I waded into the river and climbed onto the rock with hopes of catching a trophy trout. In the blazing heat of the August day, with a Joe’s Hopper on my line, the trout were proving to be quite hungry.

As the fly landed in the slow current that skirted the edge of a rock, I noticed a raft lazily drifting down the river. Two people were aboard, a man who was steering the boat, and a woman who was sitting low in the back, enjoying the peaceful ride. As they got closer, the man watched me fish and kindly commented on my casting. When I nodded and thanked him, the woman sat up. She was topless. In hindsight, I should have asked for a ride.

Some of my other most memorable moments on the water were the times I fished with my cousin Brian. As young men, we held annual “Big Fish Contests” on Lolo Creek with the wager of a chicken dinner at the Lumberjack Saloon (known today as The Jack).

I am a fly fisherman at heart and prefer to use dry flies. Brian was always gracious enough to let me try the best holes on the creek first, and when I was done beating the water, he would toss out a depth charge — a Rapala lure as he called it — and haul in a bigger fish every time. It got so bad that I would fish a hole and then purposefully wade into it splashing vigorously in an attempt to scare away any trout that might be hiding in its depths. Needless to say, it didn’t work. I lost the bet every year.

But today when I came to the river, it wasn’t to fish or relive memories of Montana’s truly great trout waters. It was to simply be with the river; to write about it. That’s it. And in my naive way, I thought I could capture the very essence of it with words; capture its soul. I was wrong.

I can write about a river in spring, as winter releases its solid grip, and the ensuing swells of water resonate like an orchestra. Or how in summer, the low flows clearly define rocks and eddies, which are perfect places for lazy trout to lay low, and also perfect for a lazy fisherman to try to catch them. And in autumn, when the tamarack trees turn the mountains into a patchwork quilt of green and gold, the sharp drop in temperature quickly cools the river and carries with it an inevitable outcome, energizing the trout for one last feast on the October caddis hatch. Then there’s the cold of winter, when ice locks the river and days are seemingly better spent in front of a warm wood stove.

But that’s not what truly defines a river, at least not for me. I cannot find words that do, and, quite honestly, I don’t want to. A river can only be experienced, which can only happen by spending time with it. And that time, in my opinion, is best spent being still and quiet. It’s in these solitary moments that it will speak. It’s a complicated, yet lovely marriage between you and the undefinable entity called a river. I’ve come to believe that a river simply… is.

As summer nears and I grow older, I plan to revisit Montana’s Blackfoot River and stand once again on a large, flat stone, making wide sweeping casts like Paul Maclean in A River Runs Through It. If I’m lucky, I’ll catch the greatest of all fish: a trout. And, if all is right in the universe, a raft will appear upstream with two people on board, one of whom is freely making the most of a brilliant summer day. But this time, being much wiser, I’ll ask for a ride.

Joe Gribnau is an elementary school teacher and the author of two children’s books, Rocky Mountain Night Before Christmas and Kick the Cowboy, which was a 2010 Western Writers of America Spur Award finalist. His articles have appeared in Western Horseman Magazine, Instinctive Archer, and Traditional Bowhunter. He lives in Walla Walla, Washington.

No Comments