09 Jun Round Up: Bison: Portrait of an Icon

Imagine this scene: You’re picnicking at a table next to the Yellowstone River on a sunny summer day. Suddenly aware of a disturbance, you turn, only to see a mass of heaving, snorting, splashing creatures swimming forcefully, inexorably, and directly at you. Retreating to cover is not an option; you’re already becoming engulfed in a powerful mass of animals whose soft grunting and collective rumbling and scrabbling hooves momentarily drown out the sounds of birdsong and rushing river. They pass by so closely that you could reach out and touch their prehistoric-looking leathery sides. Then they move on, ignoring you, singularly focused on staying with the herd, following their leader to some unknown destination.

Bison are creatures of contradiction. They may look like a cartoonist’s vision of a prehistoric animal, with their dense, humped, compact bodies on overly short legs; their curved horns and jaunty beards; their robes’ worth of fur (impossibly luxurious in places, but hanging off their bodies in ragged strips in others); and those ageless, knowing eyes. But bison are nimble, fast, and strong. They’re capable of sprinting 35 miles an hour, clearing fence-high obstacles, fording glacier-fed rivers with their calves during the height of spring run-off, and — as anyone can witness by watching the warning video on Yellowstone National Park’s website — tossing a tourist with merely a flick of their massive heads.

The animals are tough, durable, resilient, and smart. They have matriarchal leaders who employ the strength of the group to protect the young. And they evolved in perfect adaptation to life on the Great Plains. These evolutionary strategies include a metabolism that slows down in winter so they can forage less, and a habit of walking into and through storms instead of drifting with them, which prolongs exposure. The immense size of the herds, and their patterns of movement and intermittent grazing behavior, actually helped shape the grassland ecosystem. Yet in a short couple of decades late in the 19th century, these iconic creatures barely survived an assault that took their numbers from an estimated 25 to 60 million to fewer than 1,000. Bison came within a horn’s width of disappearing forever, and this makes their comeback all the more remarkable.

“For millennia, the American bison shaped the landscapes of North America and the cultures of many American Indian Tribal Nations,” writes former Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell. “With settlement, this majestic animal — the largest land mammal native to the U.S., once numbering 40 million — was all but wiped out, slaughtered at the rate of one creature every 30 seconds for 40 years. Thanks to the efforts of many Tribal Nations, conservation organizations, and members of the 114th Congress, in 2016 President Obama signed a law naming the bison America’s National Mammal as a symbol of our nation’s unity, resilience, and health, taking its rightful place alongside the bald eagle, and recognizing the bison’s critical role in supporting a balanced ecosystem that nurtures all species, including humans. In shaping our landscapes, this amazing creature, brought back from the brink of extinction, can once again lead us on a path toward a more sustainable future.”

The Standing Rock Sioux Indian Reservation straddles the border of North and South Dakota. There, Ron Brownotter, who is of Lakota-Yanktonai descent, runs 600 heads of buffalo over 20,000 acres. After two decades of bison management, his land is flourishing. “We have birds, insects, snakes, coyotes, badgers, deer, skunk, even wolves and moose, prairie dogs, eagles, and hawks,” he says. And his ranch is believed to be the largest bison enterprise solely owned by an American Indian in the U.S. or Canada.

Brownotter finds the ultimate fulfillment in raising bison. “I describe it like putting on a glove; it fits my hand,” he says. “My culture, the land, the buffalo, are all mixed together. I feel my mission today is to raise them, bring them back, and be a help to my community, my family, the reservation as a whole — and to know that the buffalo have returned.”

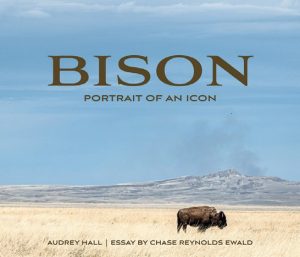

Excerpted from Bison: Portrait of an Icon (Gibbs Smith), a newly released book that celebrates America’s National Mammal, by Chase Reynolds Ewald and photographer Audrey Hall.

No Comments