07 Jun Stepping Out of the Shadows

Looking at it from a certain perspective, John N. Maclean was a successful writer long before his famous father, Norman Maclean, made his mark on American literature. But when the time came for John to write his first book, his father’s reputation — although he was by then deceased — cast a long, deep shadow that was based on two legendary works: A River Runs Through It and Other Stories, published in 1976, and the posthumous Young Men and Fire, published in 1992. The title story of the first book alone immortalized the elder Maclean, earning him comparisons to Ernest Hemingway and William Faulkner as a stylistic innovator.

In my opinion, A River Runs Through It contains some of the most beautiful prose ever written in the English language, full of the same haunting rhythms and grace as the King James version of the 23rd Psalm and of fly fishing itself, which is the story’s triggering subject, though not it’s true one. Such high art naturally attracted attention from the 1977 Pulitzer fiction jurors. Twice, they unanimously voted to give Maclean the prize, and twice the Pulitzer’s general committee overruled them. In fact, no prize was awarded in fiction that year, but the book went on to become a perennial bestseller, translated into half a dozen languages. And 15 years later, in 1992, the release of Robert Redford’s Academy Award-winning film “A River Runs Through It” coincided with the publication of the author’s second book, Young Men and Fire, which immediately became a bestseller and promptly won a National Book Critics Circle Award.

Of course, all sons live in the shadows of their fathers, at least for a time, but when yours is a famous writer, it’s different; especially for a 52-year-old who’s trying to launch a second career as an author after quitting a 30-year day job as a reporter. As a publisher friend of mine once put it, “The power of your last name might get you in the door sometimes, get you a few reviews perhaps, maybe a small feature story and a handful of sales.” The rest, however, depends on the quality of the writing. For example, who’s ever heard of Thomas Steinbeck? The shadow cast by his father, legendary author John Steinbeck, seems to have completely eclipsed his eldest son, an obscure novelist whom one of my writer friends sarcastically calls the “Son of Mice and Men.”

An angler casts into the swift current of the Blackfoot River, which served as thehome waters for four generations of Maclean fly fishers.

That same friend — a member of the Nez Perce tribe and a former wildland firefighter — once asked me incredulously, “You know John Maclean?” “Indeed, I do,” I explained. “We’ve fished together ever since he came to the college here in town to lecture.” Then, vainly hoping to impress him further, I dropped another name. “In fact,” I said, pausing briefly for emphasis, “back in the day, I even knew Norman.”

“Norman who?” came the reply.

John Maclean embarked on a professional writing career at the age of 17, and in 1965, he went to work for the City News Bureau of Chicago right as the Vietnam War was heating up. While many of the best young journalists were drafted, John was spared due to ear issues. City Press, as it was called, supplied the Chicago dailies with news stories and was a veritable Marine Corps boot camp for Chicago journalists. Its alumni list includes Mike Royko, Seymour Hersh, Clayton Kirkpatrick, Carole Simpson, and Kurt Vonnegut, and the bureau’s motto was, “If your mother says she loves you, check it out.” At City Press, you either learned to write well or you were fired.

Author John N. Maclean relaxes athis desk in the cabin his grandparents built in 1922.

Typically, young City Press journalists started as police reporters and spent three to five years learning the ins and outs of Chicago while mastering their craft. Instead, and rather unheard of, John graduated from that role in a record 18 months, followed by a meteoric rise through the reportorial ranks. At 22, he became the youngest city desk reporter to ever work at the Chicago Tribune; at 23, he was covering the criminal courts for the same outlet; and at 26, he became the youngest Washington correspondent in Tribune history. John starred in that role for nearly 20 years, 11 of which were devoted to covering the State Department.

During the Nixon years, John competed fiercely for one of two “open” seats on the infamous Kissinger Shuttle, a battle he almost always won, while the other 12 seats were permanently assigned to larger media outlets, such as the Associated Press and United Press International. I know all of this because Norman proudly boasted to me about the accomplishments of both of his children.

John’s now-famous uncle, Paul Maclean, also applied to City Press. Bored by his job as a political reporter in Helena, Montana, where he fell into debt and was known to drink, gamble, womanize, and get into frequent brawls, Paul followed Norman and his wife, Jessie, to Chicago in the late ‘30s, hoping to secure a job with a city paper. Norman sent him to George Morgenstern, a friend who had just taken the job as head of City Press. Unfortunately for Paul, Morgenstern had yet to work himself into Chicago’s media institutions, which, John notes, are still run “mostly on clout, a Chicago word that combines power, influence, and patronage.” Illustrating the point, John quotes the city’s former mayor, Richard J. Daley: “We don’t want nobody nobody sent.”

At that time, Paul was not merely a nobody in Chicago, he was a nobody nobody sent. Like Hemingway’s alleged application to City Press, Paul’s was rejected, and Norman instead helped him get a job as an assistant in the office of press relations at the University of Chicago.

On the west side of Seeley Lake,the water reflects cloud formations duringa typical western Montana sunset.

By the time John applied to City Press three decades later, Morgenstern had acquired plenty of clout, and within days of John’s acceptance, he received his first press pass. It was here that he met Frances McGeachie, his wife of more than 50 years. And once grown, their son John Fitzroy Maclean also joined City Press briefly before heading off to law school to become an attorney. (Their eldest son, Dan, writes and teaches science in Anchorage, Alaska. Seeing that writing clearly runs in the family, perhaps someday a mutant gene might produce a Maclean who can’t write his or her name in the mud with a stick.)

No, I can’t do what he did,” John tells me, referring to his father’s evocative lyrical style. “And he tried and couldn’t do what I do,” he continues, alluding to his father’s failed attempts over several years to write Young Men and Fire as a straightforward nonfiction narrative. It wasn’t until Norman treated his story — an account of Montana’s Mann Gulch fire of 1949, in which 13 wildland firefighters died — as a classical tragedy that he began to succeed. But, as John notes, by then the author was swiftly running out of time: “He was 87 when he died,” John notes. “I mean, even toward the end, he would get the manuscript and a pencil out and look at it and try to make it a go. And by then he had actually done it, but he wouldn’t let loose of it. A lot of artists hold on to a last work as they near the end, for the obvious reason that when the work of art is done, so are they.”

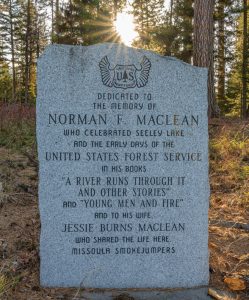

This rough-cut granite monument was erectedin 1992 to honor the author’s parents.

The week before he spoke those words to me, I’d driven to the Maclean family cabin to fish with John on the river that his father made famous, and which is now one of the primary subjects of John’s sixth book, Home Waters: A Chronicle of Family and a River. His previous five, all devoted to wildfires, have established him as one of the nation’s pre-eminent authorities in the field. His first book, Fire on the Mountain, is to some wildland firefighters what A River Runs Through It is to fly anglers. Both are what Hemingway would call “the true gen,” as in the real thing or the genuine article, and I can’t think of a time in history when distinguishing truth from falsehood has been as important as it is today.

Fishing the canyon section of the Blackfoot River with John reinforced that idea. Although it was only mid-September, an October caddis hatch improved my catch rate, and each of us caught a few truly spectacular fish along with plenty of others, whereas John usually outfishes me there. He knows it intimately, the way a lover knows the beloved, as he’s been walking its banks for almost as long as he’s been making the trip to Montana from various points east of the 100th Meridian. The cabin is the physical connection between Montana and all the members of the Maclean clan, and it has been for a century now across four generations — five if you count John’s grandchildren.

John Maclean’s grandfather, Reverend John Norman Maclean, situated the family cabin so that only one tree had to be removed— a western larch that he used in the original foundation.

The cabin sits on the west side of Seeley Lake in a monumental stand of western larch trees. A mile away, the nearly limbless trunk of a 1,000-year-old tree called Gus, the world’s largest specimen, rises straight to the sky. And nearby, a lakeside trail leads to a granite memorial that was erected by the Forest Service to honor John’s parents, Norman and Jessie. The monument, which looks like the headstone of a grave, is often decorated with tokens of respect that are left behind by those who discover it. If you stand behind it, kneel down, and look up over the highest point on the stone marker — a tiny tick of rock John showed me once — you can see the place where he scattered his father’s ashes, on one of the highest peaks in the Swan Range.

Grief has no end. Recollected now across the prolonged months of a catastrophic global pandemic, those summer-like days I spent with John on the water seem timeless and everlasting, less like life — which in the words of his father, usually goes “sideways, backwards, forwards, or nowhere at all” — and more like a story John or Norman might create, one that “lines out straight, tense, and inevitable, with a complication, climax, and given some luck, a purgation, as if life had been made and not happened.”

The Girard Grove in Seeley Lake is home to Gus,the world’s largest west-ern larch tree,which stands 163 feet high and has a circumference of 273 inches.While mostof the larch trees in this grove are around 600 years old on average, Gusis estimatedto be around 1,000.

The purgation, I suppose, was the releasing of the trout after the ritual violence of catching them. The story’s denouement came swiftly the moment I put my car into reverse to head home. I looked out of my windshield toward the front door of the cabin, where I saw John standing in the shadows. Then, he stepped forward into the sunlight with his hand raised in that universal gesture of farewell. When I glanced into the rearview mirror moments later, he was still standing in place with his hand raised toward the sun, smiling.

No Comments