23 Nov Portraits of Humanity

In the oldest reaches of downtown Missoula, Montana, there’s a haunt where the walls have eyes. Inside a storied brick building, where no signs announce its presence, is a place that some might call a dive. But Charlie B’s is no ordinary bar; step inside, and you’ll find walls plated with a vintage collection of unadorned, black-and-white portraits that occupy an overlooked niche in the photographic history of the American West.

For years, maybe decades now, my friends and I have come to Charlie B’s — a celebrated, guileless gathering place also known by its cosmic nickname: A Corner of Space and Time. Relaxing with beers in hand, a century-old, battered wood floor at our feet, we theorized about the mysterious faces staring back at us from the large, soulful portraits taken by an unknown photographer from some distant past. We watched tourists and university students filter through, perhaps unsure of the place itself but aware that the pictures on the walls were worth a visit to this unscrubbed saloon. Many looked for a few minutes and left quietly, leaving the rest of us to enjoy our drinks, food (from the Cajun kitchen shoehorned in back), and the ragged conviviality of the place.

About 300 of Nye’s images line the walls of Charlie B’s, spanning four decades of his work. Photo by Aaron Teasdale.

Everybody seemed to have a theory about the pictures: Since the building was once a brothel, perhaps the portraits were of its customers. Or maybe the bar’s owner and namesake, Charlie, took the photos. No one seemed to really know for sure. One day over local ales, my friend Ben Ferencz and I vowed to learn the real story.

First, we went to Charlie, who, it turns out, is not much of a talker. He did, however, point us toward the photographer’s widow, Jean Belangie-Nye, who we called on next. It was from her that we learned these portraits were original darkroom prints taken a half-century ago, and the only copies were those hanging on walls of this bar. Imagining a fire or other future calamity, my friends and I realized we needed to act fast. Soon, we were scanning old negatives and interviewing grizzled bartenders and the few remaining regular customers from that era in a quest to preserve the portraits and their most unusual history.

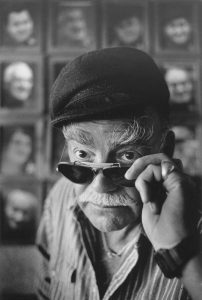

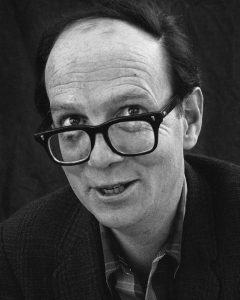

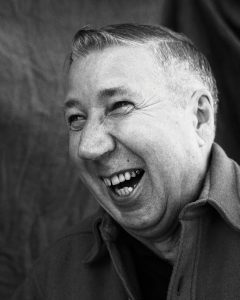

Photographer Lee Nye stands in front of his “Eddie’s Club Collection.” This photograph was taken sometime in the 1990s by Michael Gallacher.

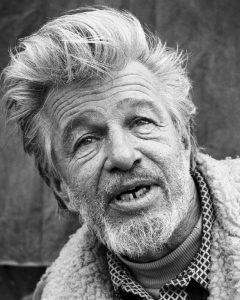

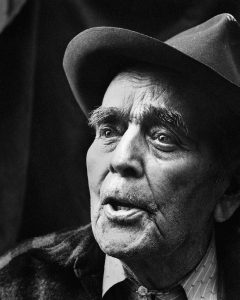

In the 1960s, this bar on the ground floor of the old Belmont Hotel was a workingman’s watering hole known as Eddie’s Club. It functioned as a sort of community center for retired railroaders, loggers, and worn-out blue-collar sorts, men who’d lived through the wrenching scarcity of the Great Depression and endured unimaginable violence in the battlefields of World Wars I and II. They’d hewed with crosscut saws, wrenched railroad steam engines, and driven pack trains into high alpine terrain. Now in their later years, knowing something in life had passed them by, they came to Eddie’s looking for succor and a humble place to sit.

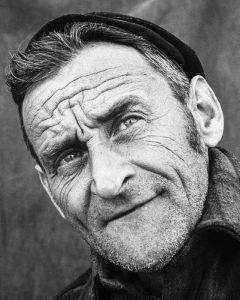

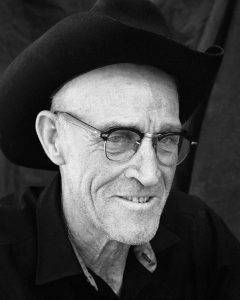

- Al Normandeau

- Joe Molatare

As the story goes, one day in the early 1960s, photographer Lee Nye stepped into this graying clubhouse. Nye had grown up in Eastern Montana, where he was known as a rebellious, railcar-hopping, horse-whispering teenager. As a young man, he discovered photography and headed to California to study his craft, learning from the likes of Edward Weston, Ansel Adams, and other masters of the medium. He was also said to have run around with Jack Kerouac and other Beat Generation characters. A subsequent stint in Los Angeles shooting commercial photography left him financially rewarded, but spiritually hollow.

- Willis Stewart

- Danny Hunter

So he returned to the gritty grandeur of his home state, and in 1965, Nye took a job as a bartender at Eddie’s. There, he quickly bonded with the bar’s elders, the kind of hard-laboring, plainspoken men he’d grown up with, who were a world away from the smooth-talkers he’d met in California. In time, he became something of a caretaker, dispensing health advice along with cold beers. He loaned the regulars money, employed some for odd jobs, and hired taxis to take them home when needed. He was even a pallbearer for more than one when their time inevitably came to an end.

Not long after he started working at Eddie’s, Nye led one of the old-timers to the alley out back to take his portrait. He clicked the shutter on his camera, and a photography project like no other was born.

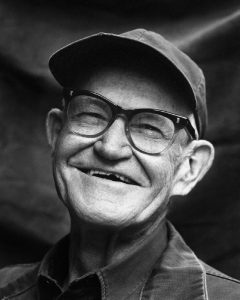

Nye arrived to work with his Rolleiflex 2-1/4 medium-format camera and a charcoal-colored sheet to use as a backdrop. The customers he chose to photograph in that back alley, both men and women, were usually those with scars, complicated stares, and stories creased into the lines on their faces. And he always shot the portraits in the morning, when the rays of the slanting sun didn’t yet penetrate the narrow urban canyon of his “studio.”

- Jack Mote

- Claude Parsons

Nye wasn’t interested in posed portraits. Instead, he wanted pictures that conveyed a sense of honesty and authenticity. He’d have his subjects sit on the steps of the fire escape, then chat with them to take their minds off the camera, which was balanced against his chest. Down-to-earth and gregarious, he’d often tell jokes or talk about the railroad and the war, and when the moment was right, he’d quietly press the shutter. Most subjects didn’t even realize when the picture was taken.

“You think all this occurs in the camera; it happens there, but it isn’t from the camera,” Nye explained in a 1993 interview with photographer David Spear. “The Eddie’s Club portraits formed and formed and formed with every beer I drew for these guys, or every discussion we had, [and] all the BS that went into those. This is a bar where people visit, drink, get acquainted, [use as] their second home, get lost, get found, all kinds of things happen there.”

- Wishbone Moy

- Bob

From 1965 to 1973, Nye tended bar at Eddie’s and created these images in the alley. A maestro in the darkroom, he spent countless hours developing the portraits and mounted the resultant 16-by-20-inch prints on the walls of the bar, where they remain to this day. His effort resulted in what’s called the “Eddie’s Club Collection,” a singular achievement in 20th-century American photography, due to the fact that they are not only authentic — as in unposed — but also because there’s nothing else like them in terms of subjects, setting, time-period, and quality.

- Tony Cronin

- Slim Pickins

In an article in the online publication “Hyperallergic,” noted art critic and poet John Yau points out that Nye’s portraits were created a decade before the much-heralded portrait series “In the American West,” created by famed East Coast photographer Richard Avedon after he traveled around the Western U.S. for five years photographing the hardworking, everyday people who crossed his path. Yau explains that, “Avedon … objectifies [his subjects], which Nye never does. Nye’s photographs are about who the men are and how much can be glimpsed in the gaze of his camera.”

- Charlie Hall

- Betty Reynolds

Eddie’s Club had always been a refuge for the working class, and under Nye’s influence, it also became a stronghold for creatives, as one of the American West’s most unexpected cultural melting pots. The “Eddie’s Club Collection” eventually grew to incorporate 125 portraits, including photos of poet Richard Hugo, novelist James Crumley, Irish poet Anthony Cronin, and artist Jay Rummel. Writers James Welch, James Lee Burke, William Kittredge, Edward Abbey, and Allen Ginsberg were also among the regulars or visitors who frequented this haunt.

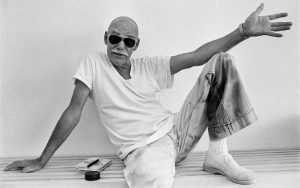

Photographer Lee Nye poses in downtown Missoula. Photo by Michael Gallacher

In the 1980s, when the bar became known as Charlie B’s, the owner commissioned Nye to create a new series of 8-by-10 portraits that became known as the “Charlie B’s Collection.” Nye continued adding to it until the year of his death in 1999. These, along with a series of more recent digital photos of current regulars, are stitched together like a cross-generational quilt, covering nearly every inch of the bar’s walls.

Today, visitors to Charlie B’s share drinks and stories beneath the gaze of those who did the same a half-century before, connecting us to an increasingly forgotten past. As Missoula poet Dave Thomas — who first came to Eddie’s on the night of his 21st birthday and is a regular at Charlie B’s now in his 70s — puts it, “They transmit an awareness from one generation to the next of humanness.”

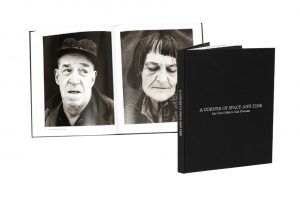

Editor’s Note: Aaron Teasdale worked with a team, including designer Ben Ferencz, Lee Nye’s widow Jean Belangie-Nye, and others, to create the fine-art book A Corner of Space and Time: Lee Nye’s Eddie’s Club Portraits. It features the entire “Eddie’s Club Collection,” printed in duotone with black and metallic silver, and it includes biographies of each subject, historical essays, and a long-form interview with Nye. Learn more at cornerofspaceandtime.com.

No Comments