12 Aug Uplifted in the Outdoors: Montana Landscape Painter Greg Scheibel is Guided by the Light

IN A WELL-APPOINTED GALLERY IN NORTHWEST WYOMING, the landscapes painted by Montana artist Greg Scheibel refuse to go unnoticed. It’s not that the paintings act as come-hither sirens; instead, they are muses who weave quiet but insistent spells of light, shadow, and subtle color upon observers until they, too, enter the enchanted landscape.

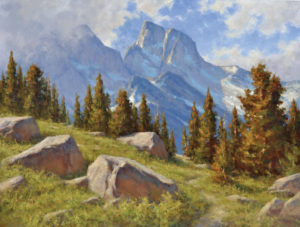

“Morning in the Tetons” | Oil | 36 x 48 inches

Scheibel presents himself as a workman-like artist even as his paintings push toward the sublime. His modesty becomes him, as does his willingness to be guided by the inspiration of the light. Scheibel painted almost exclusively outdoors for several years while continuing to adhere elsewhere to the discipline of life drawing. “I’ve always felt that the ability to draw is very important regardless of what kind of art you’re trying to do,” says Scheibel, whose work is sold in such Wyoming galleries as Astoria Fine Art in Jackson Hole and Simpson Gallagher Gallery in Cody.

The award-winning painter’s approach to art is akin to his approach to life: He gives all of his heart and mind to the work taking shape with hands that have spent decades installing drywall. In 2007, Scheibel retired from working as a drywall contractor in Bozeman — where he is now represented by Montana Trails Gallery — to pursue his passion for painting.

Rocks and Riffles | Oil | 12 x 24 inches

Scheibel’s inherent skills were refined in workshops with such talents as landscape painter Matt Smith and artist Kevin MacPherson, but his eye for art needed no fine tuning.Years before he picked up a paintbrush to depict mountain majesties or autumnal aspen trees, Scheibel and his wife had gathered a gem of a collection that includes paintings by Clyde Aspevig and Quang Ho.

Mule Deer | oil | 16 x 20 inches

Plein air painters like Scheibel must have a willingness to work with nature — and its myriad moods — in order to depict it. Yet the implicit challenges yield generous rewards. “Working outside means you’re dealing with changing weather and light conditions, but you do have the advantage of painting what you’re actually seeing; you can see into those shadows, you can watch the light change on a form,” he says. “That compares to a landscape painter working strictly from photographs, meaning he or she will see the landscape as the camera sees it.”

Mountain Oasis | Oil | 36 x 36 inches

As Scheibel sees it, so is the canvas transformed. The scenes he depicts, from the spiky elegance of a pine forest to the cascading cold of a mountain stream, are part truth, part fiction — or such stuff as artists’ dreams are made of. Yet the same discipline that saw him work long and hard hours to build his drywall business is in play for Scheibel as a professional artist. “Painting is self expression. I want to add my personal touch but remain true to the subject,” he says.

Susan Gallagher, owner of Simpson Gallagher Gallery, has represented Scheibel’s work for more than a decade, beginning around the time that he became a professional painter. “Artist Clyde Aspevig brought him to my attention,” she says. “He thought Greg had great promise and loved how enthused he was of studying: He was free of an ego, open to advice and guidance, and had a real grasp of the fundamentals of painting and a great eye.”

Wilsall Afternoon | oil | 20 x 24 inches

Over time, Gallagher has been able to watch Scheibel’s work develop and change direction. “I feel like Greg is at a starting point in a way with subject matter,” she says. “He doesn’t get locked into Western landscapes, although it’s his focus, but he’s not afraid to take on other subjects, and his painting is consistently strong.”

Oyster Lagoon Vietnam | Oil | 18 x 24 inches

Against a historical backdrop in which landscapes were periodically presented as ideal and unchanging — places of peace amid mass societal shifts or violent conflicts — contemporary painters seeking to represent nature know, like Keats, that truth is in the beauty. Scheibel’s painting Morning in the Tetons perfectly expresses that purist principle. The work, like a Rubens painting or Roman architecture, has sufficient merit tied to its size, with the oil measuring 36 by 48 inches. There is still more that meets the eye — and fixes it. The painting expresses the essential nature of that place, that hour, those peaks, and such snow. “Often, it’s as though you’re trying to capture the intrinsic quality of the place, which is not always easy to define,” Scheibel says.

As for the eternal question, loosely defined as why artists of the ages used landscape elements without making the environment the sole subject matter, Scheibel argues that such scenes evoke a sense of connection in the observer. “Landscape is a living thing that we all relate to; it resonates with just about anybody,” he says.

December Lilacs | Oil | 30 x 24 inches

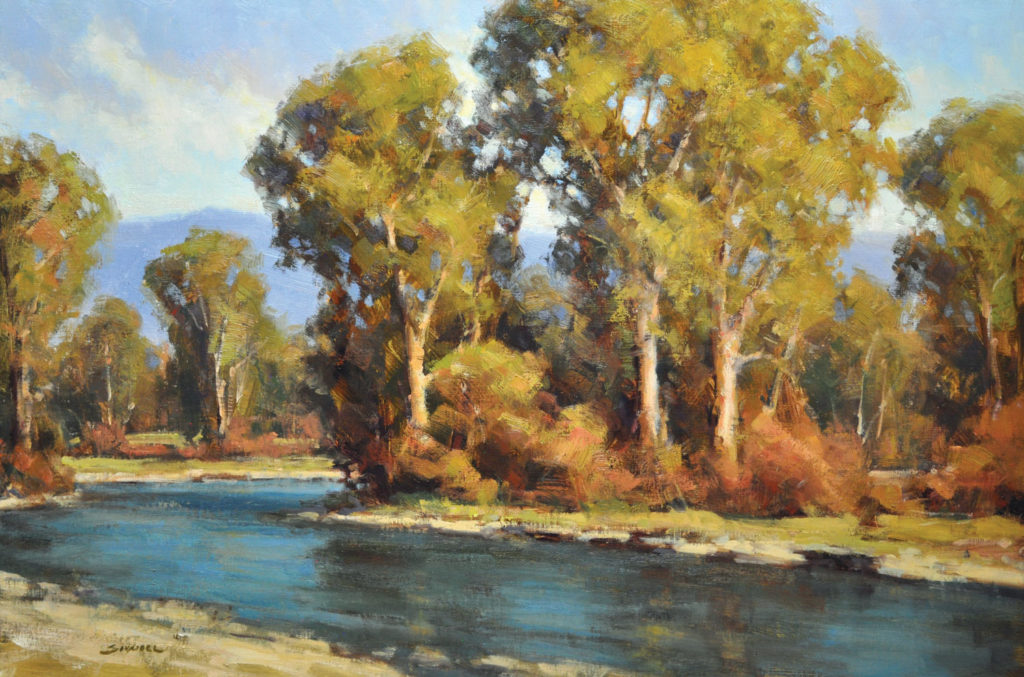

The painting Autumn in the Bitterroot cannot create more resonance than it does simply by virtue of its masterly design. The oil depicting the change of cottonwood trees along a winding stretch of stream inclines toward geometric shapes only to soften straight edges. The strongly horizontal scene demonstrates a plein air painter’s truism: Water takes on aspects of its environment. “Water is completely influenced by its surroundings: the sky, the backdrop, the weather … bringing up ripples or waves, going from calm to agitated, picking up the light of the sky or going to a stark gray,” Scheibel says. “It can be brilliantly lit up or the darkest subject of the painting; you just have to observe and do the best you can to convey what you see.”

What Greg Fulton, owner of Astoria Fine Art, sees in Scheibel’s work is all that is needed to attract the viewer’s attention and admiration. “Greg has mastered what can only be described as beautiful lighting. His work translates extremely well with our clientele,” he says.

Autumn in the Bitterroot | Oil | 20 x 30 inches

No Comments