11 Jun On Fred Beckey’s Shoulders

The legacy of an obsessive and brilliant mountaineer

In 1972, the summer after doug McCarty graduated from high school in Bozeman, Montana, he and a friend hopped a freight train to Seattle. Another friend was something of a climber there and knew Fred Beckey: a Seattle-based legend who had established himself as one of the leading alpinists in North America. Introductions were made. Within days, McCarty was sharing a rope with Beckey.

“I had no idea why Beckey would climb with high school kids,” McCarty remembers. “He was already an old guy of 50 by then. I thought you had to be famous, but it became clear that if I could carry a pack, hold a rope, and manage myself on a rock face, I was a partner. It was not unique to climb with Beckey. I think Beckey may have had more climbing partners than anyone in history.”

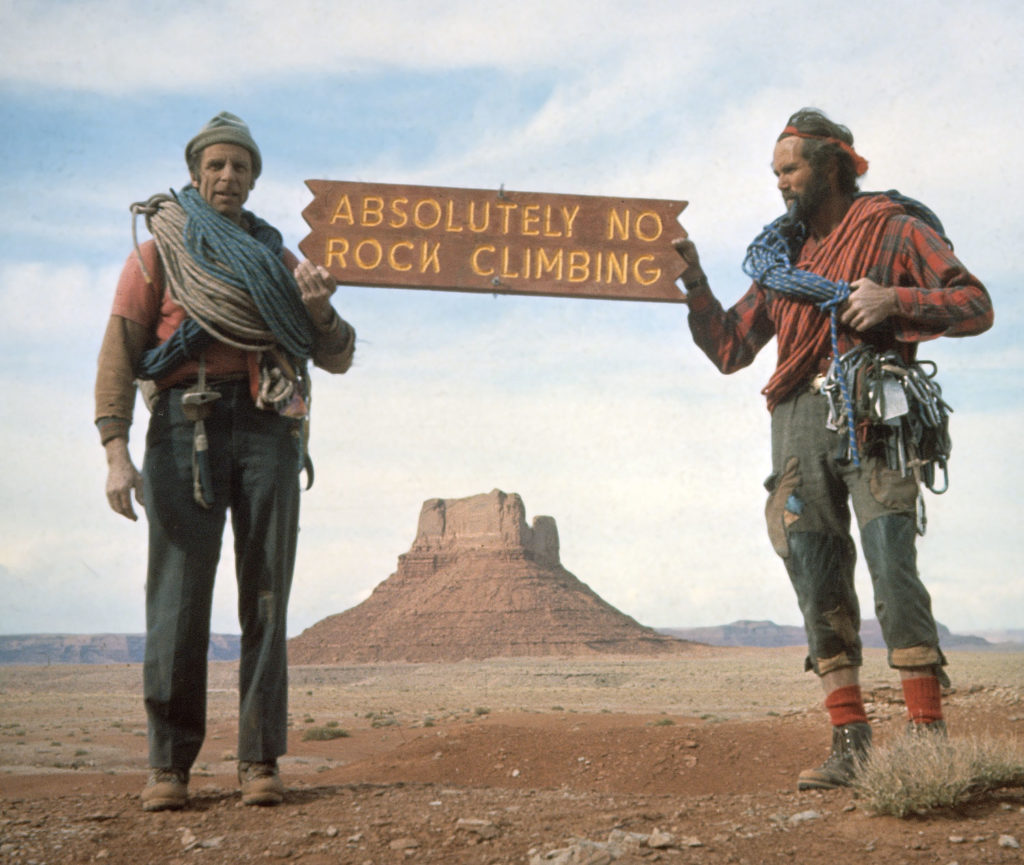

Beckey and Erik Bjornstad (right) in Monument Valley, Utah. In what has become one the the many iconic Beckey photos, the climbing duo found humor in this sign. Photography: Lin Ottinger | Eric Bjornstad Collection.

Beckey’s drive to climb necessitated willing collaborators, and anyone with the requisite skills was a candidate. Who he was with was entirely secondary to his overwhelming need to climb. The fact that Beckey burned out partners with his obsessive drive for the next first-ascent conquest meant that he had a constant logistical problem lining up folks on the other end of the rope.

A remarkable number of those collaborators over the decades have had ties to Montana, and especially to Bozeman — climbers like McCarty, Pat Callis, Rick Reese, Conrad Anker, and Jack Tackle, to name a few — and have their own impressive resumes and lists of first ascents in the airy heights of mountaineering.

McCarty and his friend spent the next weeks of that teenage summer roaming around the Northwest and British Columbia; it was part road trip, part first-ascent quest, part initiation into life-with-Beckey. Then, without warning, Beckey tired of their company and kicked them out of the car in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, where they were promptly arrested for hitchhiking on the freeway. “On one level, he was kind of a rude old man, but he must not have hated me too much,” says McCarty. “After that, we climbed together all over the West, as well as in Mexico, Tanzania, Alaska, and China through the 1970s and ‘80s.”

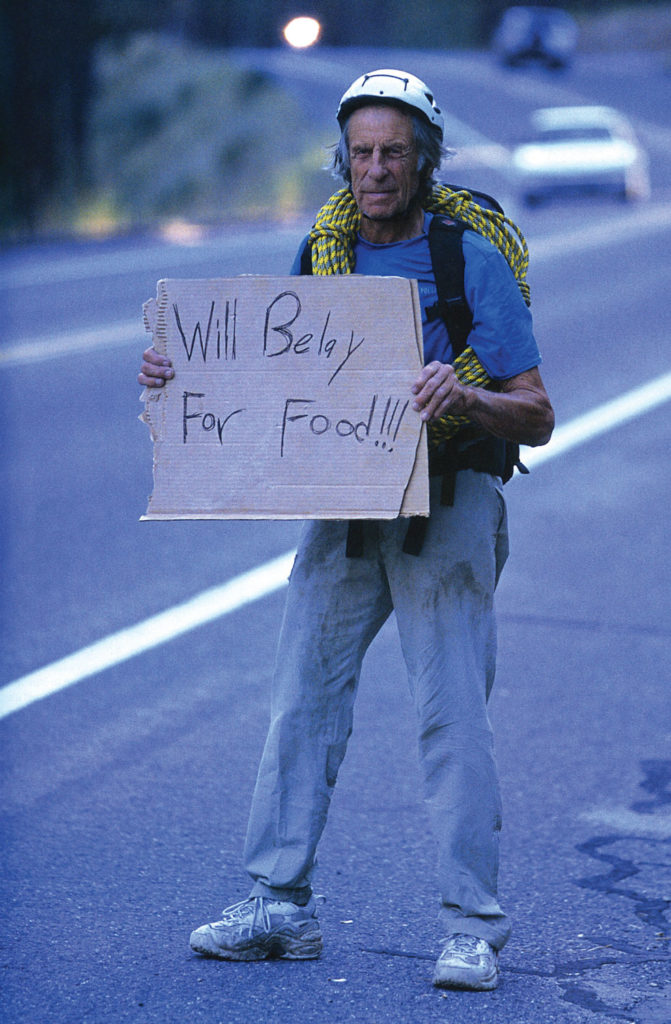

At 82 years old, while visiting friends in South Lake Tahoe, Beckey thought that holding a “Will Belay for Food!” sign would make for a funny photo. His friend Corey Rich and a few others helped him stage this iconic image, serving as a reminder of the climber’s great sense of humor. Photography: Corey Rich.

A few years after meeting Beckey, McCarty pioneered a bold first winter ascent of the north face of Montana’s Granite Peak, including a grueling summit bivouac at minus-30 degrees. “I probably wouldn’t have done that if I hadn’t spent the summer before climbing with Beckey,” he says now. “I got infected with Beckey-disease!”

Beckey’s fire for exposed mountain faces was lit early. Born in Germany, Beckey came to the U.S. with his family as a toddler, and eventually landed in Seattle, where he spent his youth. By the time he was 13, he was already busy exploring in the Cascades. He joined the Boy Scouts and quickly outstripped the merit-badge routine in his quest for new mountains to climb. Often his early partner was his younger brother, Helmut, who joined him on a variety of mountaineering escapades. Beckey cultivated a habit of identifying ascents deemed “unclimbable” by alpinists at outfits like the Seattle Mountaineers, studying them, and then bagging them.

One by one, he proved the experts wrong, embarking on a lifelong list of first ascents beginning with Mount Despair in the North Cascades at the age of 15, and ticking them off steadily for the next 70 years. It was an epic era of climbing conquest, and Beckey was at the forefront of it. While a precise number is tough to pin down, Beckey’s first-ascent list runs into the hundreds, a number widely believed to be unmatched, and at this point, arguably unmatchable.

More important is the extent to which Beckey, through his sheer will, energy, and meticulous planning, expanded the boundaries of the possible in the alpine world. In that regard, everything that has followed, including the current era of free-solo climbing, has been built on his indomitable legacy.

In 1942, Beckey secured his youthful reputation with a heroic second ascent of Mount Waddington in British Columbia. The Beckey brothers, ages 19 and 17, spent some six weeks thrashing through the Canadian wilderness, shuttling gear from the coast to the base of the peak, and making their assault on the South Face. First climbed in 1936, Waddington’s formidable face and remote location made any attempt heroic by definition. That two teenage brothers pulled it off in a feat of endurance and skill got the attention of the climbing world. It would be another 35 years before Waddington was climbed again.

Beckey on a climbing trip in British Columbia’s Waddington Range in the early 1960s. Photography: Don Liska.

What sets Beckey apart from other elite-level mountaineers is his focused obsession with first ascents. While climbers like Royal Robbins or Yvon Chouinard used their climbing exploits as a springboard to establish businesses and nonprofit organizations, or to pursue other tangents in life, like having a family, Beckey never wavered, never got distracted. Climbing was his purpose, full stop. Everything else — relationships, jobs, career, material wealth — came in a distant second. “If he could have, Beckey would have climbed every day of his life,” says Rick Reese. “And he came pretty close to achieving that.”

Reese met Beckey at a climbing slide show in the Salt Lake City area. Reese was only 20, but he had already spent years putting up routes in the Wasatch Range. After the show, he approached Beckey and suggested a route up the West Face of Lone Peak. He showed him a picture. Beckey studied it for a minute. “Let’s go,” he said.

Two days later, they were on the climb. “He taught me a lot about being safe, and about the value of careful planning,” says Reese. “That first day, he had me lead the first pitch. He complimented me, but he also pointed out a couple of places where I made mistakes. I was chastened, in a good way.”

Reese climbed off and on with Beckey over the next few decades. “He wore out his partners,” Reese says. “He had an absolute mania about first ascents. He kept a secret notebook of his routes, locations, and an endless to-do list of climbs to come. It wasn’t unusual to get back to a trailhead after a full day of climbing and drive 500 miles through the night to get to the next target. He was indefatigable, and he was haunted by the prospect of another climber beating him.”

Beckey studied aerial photographs, pored over maps, researched geologic survey reports, and knew about places that no one else did. Some of the places he explored didn’t even have maps. All of this was before anything like Google Earth or GPS. “It was also before sticky rubber climbing shoes or elaborate protection devices,” Reese points out. “Beckey climbed in full mountaineering boots, customized some of his protection out of 4-by-4-inch lumber, and carried heavy packs. The approaches to climbs could be epic efforts, thrashing through avalanche debris, bushwhacking to the base of rock faces. Being obsessive-compulsive has to enter the conversation. There is no other way to explain the range and breadth of his climbing accomplishments.”

Beckey on a climbing trip in Red Rocks, Nevada, at 86 years old. below: The film “Dirtbag: The Legend of Fred Beckey” was created by his friend and climbing partner, filmmaker Dave O’Leske, and was released in 2017. Photography: David O’Leske.

The last time Reese remembers climbing with Beckey, the climb started with a crux 5.10 pitch. Beckey, well into his 70s, said he wanted to tackle it. Reese watched him work every angle trying to get up the face. In the end, he gave up, but then took on an alternate chimney route nearby. “I could hear him rummaging around in there,” remembers Reese. “He must have spent half an hour grunting and working at it, and finally got up. I had to follow him, and it was tough. Even as an old man, Beckey never understood the notion of limitations.”

Beckey has been famously labeled a “dirtbag,” most notably in the movie by that title produced by Dave O’Leske, which documents his life. Arguably, the term fits, but it also constricts the full weight of the man and his accomplishments.

Jim Stuart

Yes, he poached campsites in city parks, slept on the sides of highways on the way to climbs, held onto his McDonald’s coffee cup for months to get free refills, drove clunker vehicles he had to park on a hill and jump-start, scrounged food at hotel happy-hour smorgasbords, stashed gear behind friend’s couches, burned bridges by taking advantage of those friends (including his brother), shaved in public bathrooms, and was the billboard image for the disheveled and rumpled dirtbag lead role. But that style evolved out of his unwavering priority, and his unwillingness to fritter away money or indulge in any kind of luxury that might limit his ability to climb. “Every dime he had went into climbing,” says McCarty.

What the term doesn’t encompass is the elegance and rigor of his driven life. Beckey is credited not only on hundreds of first ascents, with many of those routes being beautiful in scope and even artistic, but his guidebooks to climbing in the Cascades remain essential reading and sit on the bookshelves of young climbers everywhere. He authored a number of books, including the three-volume Cascade Alpine Guide published by Mountaineers Books.

Pat Callis, now a member of the chemistry department at Montana State University, cites Beckey’s work, Range of Glaciers, as evidence of his “genius.” The deeply researched book, focused on the Cascade Range, runs more than 500 pages and includes 47 pages of detailed notes. Not exactly what you’d expect of a dirtbag.

Fred Beckey’s 100 Favorite North American Climbs is another example of his meticulous documentation of rock faces, exquisitely detailed climbing routes, and thorough backgrounds of each one. The writing isn’t bad either.

When O’Leske first approached Beckey with the idea to make a movie about his life, Beckey responded in curmudgeonly fashion. “Who the hell would watch that?” he barked.

Beckey and filmmaker Dave O’Leske onstage after the world premiere of the film “Dirtbag” in Telluride, Colorado. Beckey was 94 years old and received a long, sustained standing ovation. Photography: Adam Brown.

O’Leske dropped the topic for the time being and simply spent time with Beckey, climbing, traveling, and filming with him as he aged. For a dozen years, they traipsed around the world, climbing in China and the U.S. “He had an agenda that drove him,” O’Leske says. “He was still climbing 5.8 routes in his 80s, taking on climbs with long approaches and difficult pitches. People wished he’d slow down and adjust his ambition as he aged, but that wasn’t who he was.”

Beckey failed more frequently as he got older, partly because of his physical limitations, partly because his expectations remained so high. “Even after he had to admit defeat,” remembers O’Leske, “on the way back to the trailhead he’d be planning the next exploit.

“I interviewed many of his climbing partners,” O’Leske continues. “They’d climb with him for a while, then take a break from the intensity. He burned some bridges, for sure, but most people kept coming back because they admired him and considered him a mentor. Most people forgave him in light of his brilliance.”

In later years, Beckey was slowed by a congestive heart condition. Even so, he kept climbing into his early 90s. During his last year he lived with close friend and biographer Megan Bond in Seattle. His health dwindled. He died there in 2017, at the age of 94.

In typical Beckey form, he had already booked a flight to India for the following year. He had some climbs there to check off his list.

Scott Jouppi

Posted at 00:07h, 23 AprilFred will be remembered by my wife & I until we are gone. Thankfully there a few guys and gals younger than us that we introduced Fred to in South Central will carry his story and hopefully his ambition to keep climbing.