11 Dec The Patrolman

After 37 years, Big Sky Resort’s ski patrol director is hanging up his coat and cross

During his first week of work ski patrolling at Montana’s Big Sky Resort in 1982, Bob Dixon was buried in two avalanches. He also saved someone’s life.

By that time, the 33-year-old had three years of patrolling experience under his belt, from working at Park City and Park West (now the Canyons) in Utah, and it appeared that he would need every ounce of it. That first season, there were only seven people on the Big Sky patrol, and the snowpack was unstable. On day one, Dixon responded to an avalanche in the area known as “The Bowl,” and wound up treating a skier with an open femur fracture. On day two, he was swept over a cliff by an avalanche and completely buried. And a few days later, Dixon was again buried in another slide, this time up to his neck.

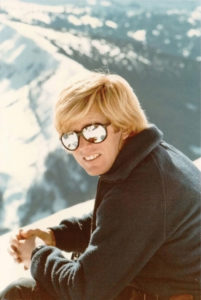

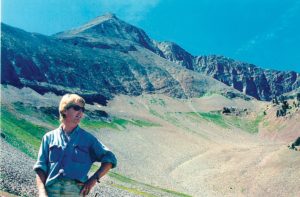

Bob Dixon, who has worked at Big Sky Resort since 1982, stands below Lone Peak.

Within two months, Dixon was appointed assistant ski patrol director, a post he held until becoming director 10 years later. This winter — after working as the Big Sky ski patrol director for 26 years and watching the resort evolve from a locals’ mountain to a world-class destination touted for having the biggest skiing in America — will be his last.

When I meet up with Dixon in late September 2018, there’s already snow covering Lone Peak, with the ski season still months away. It’s noon on a Thursday, and so far he’s held a 7 a.m. meeting and interviewed two ski patrol applicants for the upcoming season. I walk into his office on the third floor of the Huntley Lodge, and before I can sit down, he’s summoned over the radio. Apparently, someone from the National Ski Patrol is here for a Montana Ski Area Association meeting, and they are checking to see if Dixon wants to join them (he doesn’t).

I know Dixon from my five years of ski patrolling at Moonlight Basin before it merged with Big Sky in 2013, and he says that’s part of why he accepted my interview request. “If I do an interview now, with anybody, I want it to be about the patrol and how [we’ve] grown,” Dixon says, as we walk through the Huntley. “Not about me, but about the patrol. Don’t get the casket out yet.”

That’d be hard to imagine since Dixon, 69, seems ageless with a thick head of cinnamon-blond hair and a wide smile. Until recently, he worked six days a week each winter, and has handled one of the most difficult avalanche control routes on the mountain, the High Traverse. “It’s very aerobic, it’s got a lot of adventure on it, some good skiing eventually,” Dixon says, now sitting in the Mountain Mall cafeteria. “Once you come around The Bowl, you’ve got to hike back up, sit there, wading through 2 or 3 feet of snow. I like that.”

That’d be hard to imagine since Dixon, 69, seems ageless with a thick head of cinnamon-blond hair and a wide smile. Until recently, he worked six days a week each winter, and has handled one of the most difficult avalanche control routes on the mountain, the High Traverse. “It’s very aerobic, it’s got a lot of adventure on it, some good skiing eventually,” Dixon says, now sitting in the Mountain Mall cafeteria. “Once you come around The Bowl, you’ve got to hike back up, sit there, wading through 2 or 3 feet of snow. I like that.”

The “sit there,” which Dixon uses as a filler similar to “like” or “um,” is something he picked up as a teen, and is one of many endearing Dixonisms. He’s also famous for his storytelling; spend 10 minutes with him, and you’re sure to hear a yarn.

At age 6, as one story goes, Dixon says he made $100 a week selling golf balls near his family’s house in Colorado Springs, Colorado. He played Division I hockey for Colorado College, and had five front teeth knocked out — twice. He learned to ski powder in Vail’s back bowls when lift tickets were $7. He saw the Beatles and Jimi Hendrix at Red Rocks, and attended anti-Vietnam rallies while studying at the University of Colorado, Boulder. He was almost shot at the Guatemalan border on a bike trip. There are other tales that fly around on the gales of Lone Mountain like snowfall, relating to the Russian mafia, the Mexican cartel, and the Department of Defense. Some are dead true, others are big fish stories. Which is which, you’ll never know.

Early mornings are part of the job, and patrollers often start work in the dark.

“It would be the middle of December, with one of the classic Northwest snowstorms circling, and as we load the tram to go on route, Bob faithfully, with a smile on his face … would give us pure entertainment with wild stories of his past,” recalls Big Sky ski patroller Ody Loomis. “I don’t know a single person that didn’t look forward to it.”

The patrol keeps a quote board devoted to Dixon one-liners on the radio cabinet door, and among the many photos in the locker room bathroom is one of him on the Dolores River with a group of patrollers after the season ended in 1984, his skin red from participating in a “lobster bake off” to see who could get the most sunburned.

If you’ve skied at big sky enough, you’ve seen Dixon without a hat or goggles. Until the resort instated a helmet requirement last year, he wore only sunglasses unless it was around 10 below zero. “You start getting 20 below, I’ll wrap a headband around my ears and pull my neck gaiter up to hold it in place,” he says. “I like the wind going through my hair.”

A patroller zooms off on a mission.

For all of this, the patrollers love him. I’ve worked and adventured with many of them, and I know them to be a competent, athletic, and eccentric cast. These are people who wake before 5 a.m. to hike and ski exposed, wind-hammered ridges in wild weather. They carry backpacks full of explosives used to trigger avalanches. They are professional and compassionate in medical emergencies when people are experiencing some of their worst moments.

By all accounts, Dixon is a hands-off manager, known for hiring people he trusts and allowing them to use their strengths. “[He puts] what he thinks are the right people in the right place and lets it play out,” says snow safety director Mike Buotte. “[He’ll] get involved where he has to, but if he doesn’t need to … he hangs back.”

Dixon has been patrolling at Big Sky for 36 years, and has been ski patrol director for 26.

Part of that is Dixon’s style, and part is the nature of patrolling: Functioning independently in high-stakes situations is a job requirement. Besides, with 105 professional patrollers and 145 volunteers, micro-management isn’t really an option.

In addition to the larger patrol,Dixon has witnessed many other changes. “Our medical capabilities and training [have] grown exponentially. We understand the snowpack better, which makes our jobs safer. … It’s not ‘ski bum’ like when I started. It’s a career.”

In 1995, Dixon brought the volunteer patrol in-house, taking over their training and management from the National Ski Patrol. They expanded from staffing 15 volunteers on weekends only, to 10 on weekdays and 30 on weekends. Around 30 percent of new professional patrol hires now come from that program, and the volunteer training is so rigorous, it’s required for new professional hires as well.

What hasn’t changed, Dixon says, is the camaraderie, the dedication, and the love of the mountain. It keeps people around: This year they’re only hiring nine new pros.

Ski patrollers hike the Headwaters/A-Z Ridge on a route for morning avalanche control work.

Dixon has shepherded the patrol through the addition of the Lone Peak Tram and the merger with neighboring Moonlight Basin, which brought the resort to a behemoth 5,750 acres. Installed in 1995, the tram brings skiers to the mountain’s 11,166-foot summit, putting Big Sky on the map for extreme terrain. For the patrol, the changes increased the amount of avalanche mitigation work, drawing experienced patrollers from elsewhere. The merger meant bringing together two separate teams, learning new terrain, expanding facilities, and creating management schemes to ensure that it all ran smoothly.

Moonlight Basin opened in 2003 on the north side of Lone Peak, serving as a separate ski area for 10 years. When it merged with Big Sky Resort in 2013, Dixon joined the two ski patrols. He now over- sees more than 100 professional patrol- lers and as many volunteers.

Pre-merger, I had an experience with Dixon that I’ll never forget. I was working at Moonlight when a medical call came in over the radio. When I arrived, a woman was having a panic attack, breathing 120 times a minute (12 to 20 is normal). I drove her to the Big Sky Medical Clinic, but it was closed, so I tried to calm her in the car. A Big Sky patroller showed up in ski boots, scooped her into his arms, and whisked her into the clinic. When Dixon arrived a few minutes later, he knelt and took her hand. “It’s all right,” he whispered. “You’re safe. You’re doing great. Just concentrate on your breathing and slow it down.” Within four minutes, she was fine.

This calm demeanor also serves him in HR situations, where Dixon has an open-door policy. “Bob can take the most tangled mess you’ve ever seen and roll it up neatly into a ball, and when that person leaves, they feel better,” says Dave Benes, one of two assistant patrol directors. “He’s an incredible listener.”

Dixon isn’t exactly sure what’s next. Since 2010, he and his wife, Evi, also a patroller, have raised alpacas, selling the fleece. The couple have separated, but he still helps her on the farm occasionally, which he’ll continue to do. He’s toying with going to Tanzania, where he’d work as an EMT at the Mountain Gorilla Institute. And with a lifetime season pass earned after three decades of work, he’ll probably keep skiing at Big Sky.

Dixon’s job as patrol director has involved year-round work on the mountain.

As for patrolling? “At this point I don’t think so, but when you’ve been doing this stuff as long as I have and it comes to that time again next fall…” he trails off, grinning. “I like sunshine, and I like the cold a lot.”

Dixon and I leave the cafeteria, and I walk with him as he heads toward a meeting with someone who’s interested in becoming the next patrol director. “I want the career to be recognized for what it really is. It’s a dedication to helping people, the human element of guest relations, and then obviously dealing with Mother Nature at her best,” he says, gesturing to the mountain. At the base of the tram, 2,200 feet above us, there’s already 5 inches of snow on the ground.

No Comments