11 Dec The Bull Sale

One of Montana’s most expensive Hereford auctions

“Would you look at the butt on that bull?” The auctioneer calls out, as smiles crack in the crowd. “Let’s start this fella out at $15,000. Anybody give me $15,000 for this bull? Cowboys, cowgirls, get your ropes ready. Oh whoooppieeeee. Would you look at that bull!”

The white-faced, penny-red colored Hereford circles awkwardly in the show ring. He’s a fine Holden Hereford specimen, the number one carcass bull at the sale. The auctioneer rides the bull’s pedigree for every dollar. “You want hip!? You want height!?” he calls out. “You want body!? Oooohh boy, would you look at that bull!” It’s high action, and there’s a buzz in the arena, a palpable excitement, although one with a serious tone.

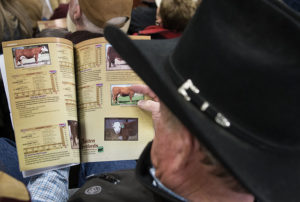

A potential bidder reviews the program prior to the sale.

Men and women in cowboy hats make small gestures to the auctioneer’s men. The flick of a finger, a short hand raise, nothing too showy, they’ve done this before. These are people who have traveled to Valier, Montana, from all over the world to buy the finest Herefords, and while many were chatty and lighthearted upon arrival, when the auction began the quieted tone meant that this was serious business. They’re here for specific bovine genetics, stuff you can’t buy anywhere else.

The man sitting next to the auctioneer in the booth at the back of the show ring is Jack Holden, age 51, a cowman like his father and grandfather before him. Jack’s daughter, Brooke, is perched next to him crunching sale numbers. His son, Brad, moves the cattle in and out of the show ring. Tresha, his wife, takes charge of everything outside of the ring: feeding the 100 or so people filtering about the ranch, greeting folks, answering questions, and pointing them in the right direction, whether it’s to the arena or to the best views.

Jack’s voice cuts in on the loudspeaker and fills the steel building. “This is a great bull, this bull comes from my favorite cow,” he says. The auctioneer takes over again, and the price keeps rising. “$27,500? 27,5? 27,5? No? I sold a bull for twenty-five thousannnd dollars!”

Jack Holden speaks to the crowd as the auction gets underway.

Holden’s ranch headquarters is a compound of sorts set in an unforgiving short-grass prairie, and made up of houses, barns, warehouses, and corrals. Further out, there’s nothing but land rolling toward the horizon and creek bottoms until you hit the Rocky Mountains 20 miles east. Located in Pondera County, the area encapsulates the irony of this part of the state: that such a huge amount of space has a very small community.

This is the land Jack’s grandparents, Les and Ethel Holden, dug into in 1954. After selling their stake in a family cattle operation in Willow Creek, Montana, the Holdens bought two old farms in Valier that had lost most of their topsoil to the incessant Western wind. Here, they got to work, planting hay and raising cattle. It’s where they built the multimillion-dollar operation that their grandchildren still run today.

In the 1930s, an agricultural phenomenon discovered at Fort Keogh Livestock and Range Research Laboratory in Miles City, Montana, changed beef production forever: A prime bull named Advance Domino 12 sired two sons, and those two bulls bred 50 premier cows, starting a strain called “Line-1 Hereford Cattle.” The offspring were, and still are, bred to their cousins or second cousins in an attempt to achieve excellent heterosis, meaning hybrid vigor or the ability to pass on desirable traits when crossbreeding species, such as a good ribeye or better calving ease. The idea originally came from corn farmers who developed crossbred crops that outperformed their inbred parents.

Potential buyers sort through the bull lot outside of the auction arena.

Les and Ethel saw an opportunity in owning a herd with Line-1 genetics. They leased a ranch near Townsend, Montana, in 1945, bought their first registered bull in 1947, and two pure heifer crops soon after. This was the start of their registered Hereford line. To this day, the Holdens have never introduced other genetics to their herd. They have grown, perhaps, the most robust Line-1 herd of Hereford cattle anywhere on the globe.

Now when Holden Hereford Line-1 genetics meet a new genetic strain, good things happen for the rancher’s bottom line. Still, it took a while to get their name and their strain out.

‘‘Right at first, he struggled along; he had a product that no one was interested in,” says neighboring rancher John Hayne. “My dad knew Les, all the cattlemen were just trying to make it in those days. I don’t think he knew it would pay. I think he hoped. He had a vision about what could happen.”

Things started to change for the Holdens in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Hayne remembers when Les sold a bull for $100,000. “That was when a cow was worth $200, and everybody around here was like, ‘Holy crap!’” he recalls. The Holdens eventually built a multimillion-dollar operation, turning the flat earth into a profit.

Bidders come from all over the world for the annual Holden Here- ford sale.

Jack Holden took over the ranch in 1987. “I was 21 when my grandpa basically handed me the keys to the kingdom,” Jack says. “We try to never forget the work my grandparents put in, and what they made.”

Still, the market has changed, and Jack has pushed his cattle further into the global market. He’s sold bulls to customers all over the world, but the family’s financial cornerstone is still auction day, a potentially fickle situation. A drought year in the Southwest or a shift in global beef prices can change everything. In 2015, a single Holden Hereford bull sold for $240,000 at the auction. At the 2018 auction, the high-dollar bull sold for $56,000.

“We don’t rely on the high-dollar animals,” says Jack. “Of course it’s nice when we sell one for that much, but we really rely on the quantity we sell at the auction.”

A bull peers through a fence while waiting for its turn in the auction arena.

Two flush competitive bidders need to be at the ranch to really make a show of it. In 2015, it was two neighboring ranchers from Nebraska with a competitive edge that drove the bull’s price up. Yet the money is never guaranteed. “It’s our one paycheck a year,” adds Tresha, as she hurries toward the calf barn after serving lunch.

It can be a long 365 days until the next one.

The morning of the auction, the air smells of thawing hay, Canada geese fly overhead, and the morning sun casts a pinkish light on the waiting herd. Mud-covered pickup trucks fill the lot with license plates from all over the country.

Walter Carlos Romay traveled from Uruguay to be at the auction. A lawyer, telecommunications specialist, and self-proclaimed Hereford man, he came to buy vials, also known as straws, of semen. Standing out against a sea of cowboy hats, he and his five business partners sport red berets and stand behind the bulls to watch their footfalls.

Potential bidders look over the lot prior to the bull sale.

“In my country, the ranches are bigger,” Romay says, gesturing to the hind end of the bull. “They must walk a long way to get food. We want the back foot to fall almost exactly where the front foot did.” Everyone at the auction is looking for physical traits that will pass on well to the next generation. An expensive bull with a broken leg or inability to breed isn’t worth much more than good hamburger.

Romay buys 1,000 straws to take home. If all goes well, 60 percent of those inseminations will bring him calves. His animals have won the status of grand champion on his family’s South American ranches that date back to the 1800s, and Romay wants to improve his herd’s overall genetics. Uruguay is less than half the size of Montana, but it exports around 5 percent of the world’s beef, and about 60 percent of that is Hereford beef.

Straws are stored at precise temperatures to keep the semen viable during trans- port across the state or the ocean.

“We all want to be called ranchers, but you’re really a grass farmer,” says Jack. He explains that Uruguay has the best Hereford country in the world. Cattle need grass, and the more of it the better. Uruguay’s warm, temperate climate rarely freezes, which makes for lush growth year-round.

Would you look at the EPD’s on this one?” the auctioneer sings out, “He’s got cow power!” EPD is a global cattle quality metric that stands for expected progeny differences, or what a buyer can expect when they breed the animal. The EPD score weighs each animal’s pedigree, health record, and how well its offspring should fare. If a Holden Hereford is crossbred with an Angus, for instance, they could put more weight on the cow with a little less feed before it hits the market. They might be a bit hardier come winter, and less susceptible to disease.

Just before the auction takes place, Bill King, son of former three-term New Mexico governor Bruce King, is waiting outside the sale barn. He’s been coming to the auction since the early 1980s from his New Mexico ranch that hasn’t had any rain in quite some time. He didn’t come out to buy anything this year, just to watch the action and study the market.

“What happens in the cattle business is that people chase fads, they like them small or big, this or that,” King says. “But the Holdens don’t. They keep them consistent, everyone knows what they’re getting.” Although King bought the top bull and top heifer in recent years, he doesn’t bid on a single animal at this auction. But that doesn’t keep the auctioneer off his case. In the middle of the sale, the auctioneer looks at him and promises that if King would just outbid the internet buyer, there’d be rain in New Mexico, “Guaranteeeed!”

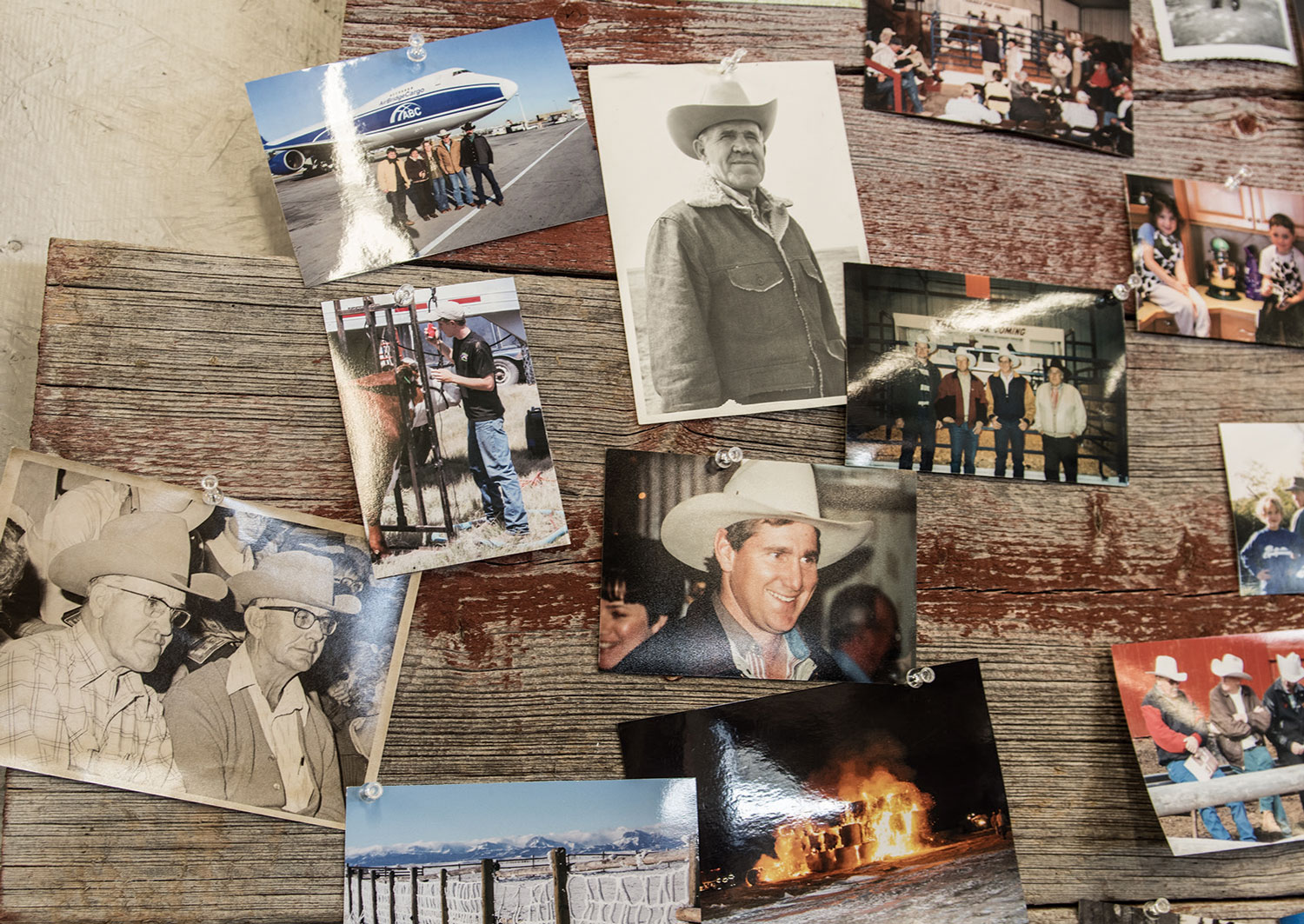

The Holden family has a long tradition of raising and selling Hereford bulls, dating back to Jack Holden’s grandparents, Les and Ethel.

Though King doesn’t comply, the Holdens still make out that day. After two and half hours of bidding, some people trickle outside to smoke or have a beverage. When the last bull leaves the ring, the sale concludes, numbers are added, and the final count is announced. This year, the Holden’s sold 175 animals in one day for an average of $8,000 a piece.

Here, in one day, on one ranch just outside of Valier, all the work that the generations of Holdens have put into their land and unique breed of cattle netted them just under $1.3 million.

No Comments