09 Aug For the Love of Cold-Water Wilderness

OBSERVATION IS CRITICAL TO THE CREATIVE PRACTICE of artist, writer, and naturalist James Prosek. Observation, and what American biologist E.O. Wilson described as “biophilia,” the instinctive bond between humans and other living systems. As Prosek explains, it’s a fascination with life and its diversity, “a deep love of the biotic world.”

This fascination led the 43-year-old artist to produce a body of work that includes paintings in major museum exhibitions, award-winning documentary films, 11 books filled with detailed watercolor illustrations, sculptures, countless drawings, and large-scale installations — all of which illuminate the beauty and complexity of nature and our relationship with it.

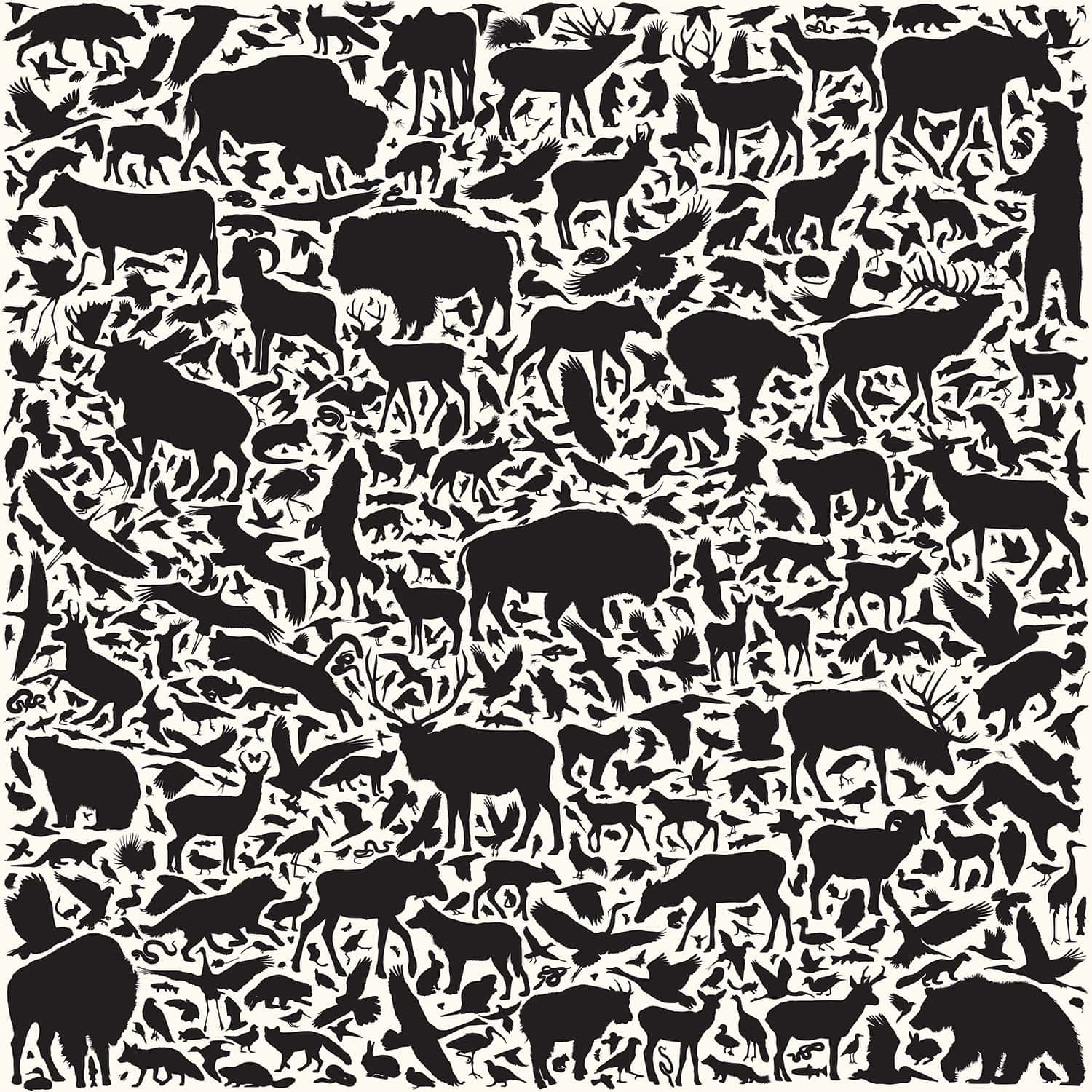

“Yellowstone Composition No. 2” | Acrylic on Panel | 45 x 45 inches

“Yellowstone Composition No. 2” | Acrylic on Panel | 45 x 45 inches

At age 20, while still an undergraduate at Yale University studying English literature, Prosek published his first book; Trout: An Illustrated History features 70 watercolor paintings of native trout from brooks, streams, and rivers across North America. He’d worked on the book since childhood, Prosek explains. The idea germinated in the ’80s when he was 9 years old and unable to find a natural history book on trout at his hometown public library. He began his investigation, writing letters to departments of wildlife around the country, and collecting pictures and information.

Yellowstone Cutthroat Trout and Wildflowers | Watercolor, Gouache, and Graphite on Tea-Stained Paper | 27 x 18 inches

“But I learned very quickly that no two biologists could agree on exactly how many trout there were,” Prosek says, explaining that this partly was due to the fact that scientists couldn’t agree on the species’ definition, and partly because the effort to categorize nature linguistically has limitations — nature’s edges are fuzzy, but categorical lines are drawn straight.

“I couldn’t really put together a list. … I thought species were confirmed, rigid units of nature,” Prosek says. “So, that’s where it kind of began for me. My faith in the reliability of these names and boundaries had begun to decompose a little, or fall apart.”

Trout: An Illustrated History was completed in 1996, and since then, Prosek’s work has earned frequent comparison with that of John James Audubon — only what Audubon is to birds, Prosek is to fish. The book was the first of its kind, and the young artist became widely recognized for calling attention to the existence and plight of wild trout and the need for conservation.

In pursuit of his creativity through observation of the natural world, Prosek has traveled across the globe. One trip took him fly fishing around the 41st parallel, resulting in another book. During college, a travel fellowship from Yale allowed Prosek to follow in the footsteps of Izaak Walton, the 17-century author of The Compleat Angler. He traveled through England and Ireland, fishing the same rivers, “each [fish] probably a descendant that Walton had caught here.”

“A Tyger for William Blake” | Oil and Acrylic on Panel | Diptych, 45 x 56 inches per panel

“A Tyger for William Blake” | Oil and Acrylic on Panel | Diptych, 45 x 56 inches per panel

The result was Prosek’s 1999 book, The Complete Angler: A Connecticut Yankee Follows in the Footsteps of Walton, which he turned into a documentary in 2002. The film won a Peabody Award the year after, and things came full circle when Prosek won the Izaak Walton Award from the American Museum of Fly Fishing in 2016.

Today, the artist lives in his hometown of about 7,500 people in Easton, Connecticut. He uses a one-room schoolhouse built in 1850 as his studio. “I still live in the same town, on the same street, actually,” Prosek says. “It’s an important source for my work. There’s a farm next to my property and a drinking-water reservoir with 1,000 acres of land; the town has a lot of open space.” Prosek grew up hiking these places with his father, who was from Brazil and shared his love of birds with his son at a young age.

“I started drawing when I was very young, probably whenever I could hold a pencil,” Prosek says. As a young boy, he copied the seascapes of Winslow Homer and the natural history illustrations of Audubon, Roger Tory Peterson, and Louis Agassiz Fuertes. “I just copied these people’s works. And I think drawing nature helped me develop an intimacy with nature, because when you draw something, you have to really examine it closely,” he says.

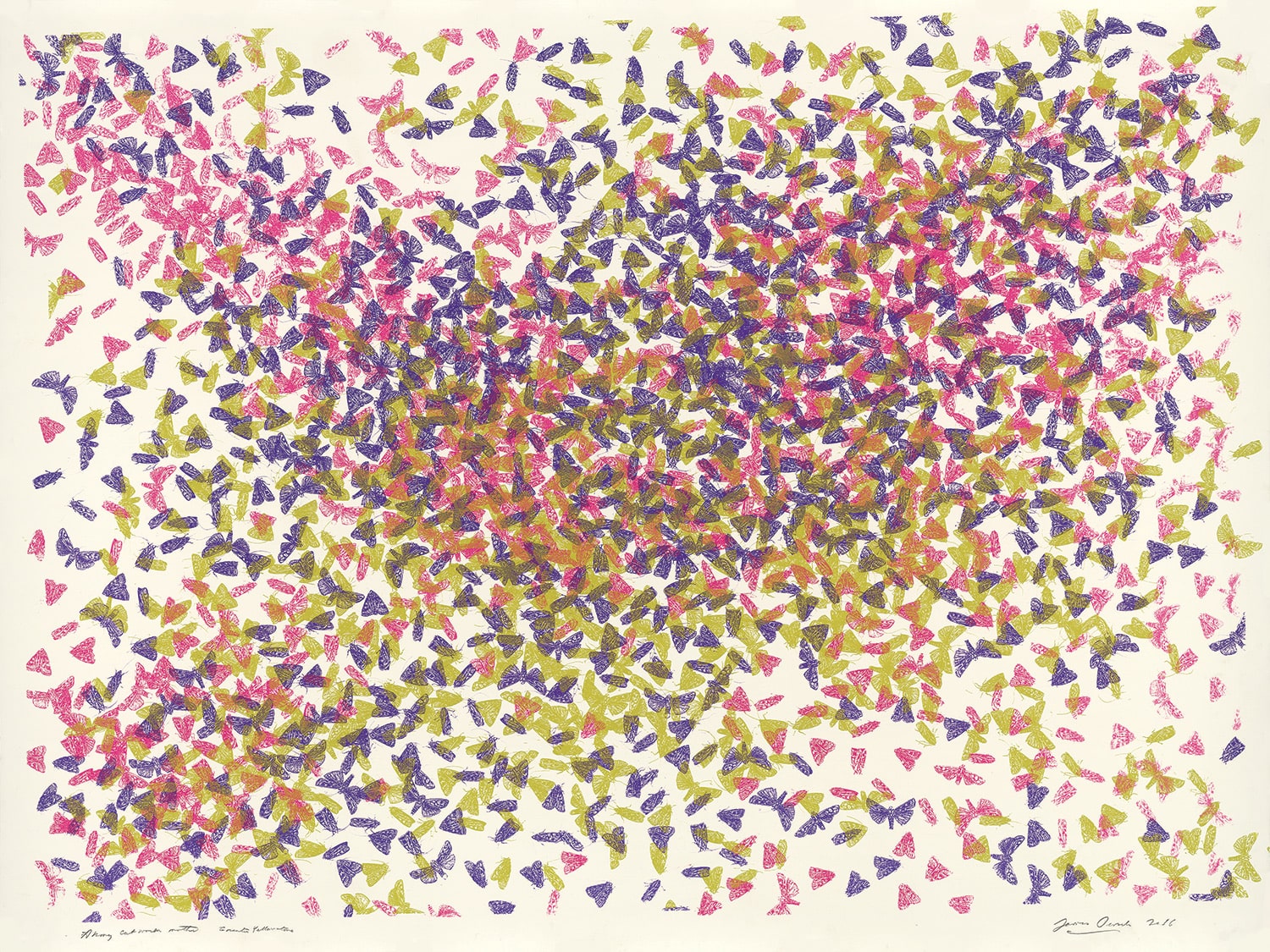

“Army Cutworm Moths” | Ink Silkscreen on Paper | 44 x 60 inches

“Army Cutworm Moths” | Ink Silkscreen on Paper | 44 x 60 inches

Prosek continues to draw from references and in the field. “Both experiences help me become a better observer, help me see, and help me fall in love with these creatures,” he says. “And the love for the animal is what eventually leads to wanting to help preserve the places where they live. So conservation just became a natural part of the effort.”

“American Elk” | Oil and Acrylic on Panel | Diptych | 56 x 90 inches

In 2004, Prosek co-founded the World Trout Initiative with Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard. They were staying at a private ranch in Yellowstone National Park and had fished Upper Slough Creek together earlier in the day. “It started over a mutual love of the fish and the habitat they live in,” Prosek says. The organization supports cold-water habitat conservation by selling t-shirts featuring artwork by Prosek, Tim Borski, and Alan James Robinson. They have given $2 million to more than 200 conservation groups.

After the publication of Trout: An Illustrated History and his other early documentary works, Prosek’s art became more conceptual, leading him back to the questions that first confounded him at age 9 when he was researching North American trout: How and why do we name, systematize, and order nature? Are there consequences?

Prosek explored this idea in the collaborative exhibition Invisible Boundaries, which opened at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming, in 2016, then traveled to the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, and ended at the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, this August. He’s currently writing a book on the subject of naming and ordering nature, and he says that Yellowstone is a good metaphor for the idea.

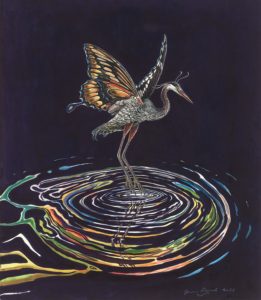

“Long-Legged Bird-Fly” (a tribute to William Butler Yeats) | Watercolor and Gouache on Paper | 17 x 22 inches

“Yellowstone wasn’t a place until someone drew a line around it and named it. It’s great it was done, because we wouldn’t have Yellowstone, but at the same time the boundary is problematic because animals don’t know it’s there,” he says. “And now, 150 years later, that line that started as a conceptual line on a map comes to mean something more real as humans push against it.”

Prosek explains that animals contend with the consequence of boundaries that humans put on the landscape. Some of these are tangible, like highways, while others are invisible lines on a map that still affect the movements of animals. An elk, for example, is a tourist attraction inside the park boundary, but across the line it can be shot and killed by a hunter. And what we’ve designated as the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is really connected to ecosystems as varied as the Great Plains, the Pacific Northwest, South America, and Canada. “Basically, humans fragment the world, but the natural world needs interconnectivity to continue,” Prosek says.

He has explored this theme in a series of painted hybrid creatures, such as parrotfish and turtledoves — representations of creatures that literally become their names in protest of being named — and painted murals that use imagery from field guides to expose our love of identification. Prosek is participating in two artist residencies, one at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, and a three-month residency that ends this fall at the Yale University Art Gallery. He is also preparing for exhibits at the Lowe Art Museum at the University of Miami, and at the Florence Griswold Museum in Old Lyme, Connecticut, next year.

What’s so captivating about fly fishing? Why does it lend itself to poetics and art so often? For Prosek, fly fishing is an extension of life — it again returns to biophilia.

“The artificial fly, made of feathers and fur, is essentially a cultural object relegated to the realm of craft, pushed aside as a functional means to an end in the realm of fine art. But the flies themselves are exquisite. They imitate an insect, fish eat the fly — you’ve essentially communicated with a fish. It’s a lot more amazing than we give it credit for. That moment and episode is just remarkable: That we can have a device that translates what we’re thinking, to what they’re thinking. That you can be connected to the fish, and you feel this pulsing animal on the line.”

No Comments