09 Aug Julia Galloway: Montana’s Voice for Clay

THE PROBLEM WITH INTERVIEWING JULIA GALLOWAY is that she’d rather talk about anything other than herself. Anything, that is, having to do with clay. “It’s kind of embarrassing,” she says. “I don’t really know much about anything else!”

Whether entirely accurate or not, the statement encapsulates Galloway’s singular focus on ceramic arts — as a practitioner, teacher, and advocate. A professor at the University of Montana and a life-long professional potter, she has shown work at countless galleries around the nation, taught workshops in all 50 states, and perhaps most importantly, been a tireless voice for ceramics. And though she may be reticent, others jump quickly to superlatives when describing the artist and her work: “ceramics royalty,” “the godmother of Montana ceramics,” “remarkable,” “incredible,” and “mind-boggling.”

The “Blackpoll Warbler plate,” a work from Galloway’s “Endangered Species” series. Photo by Maggie Hamilton

Seated at her kitchen table on a warm spring afternoon, Galloway is matter-of-fact and a little sheepish about her notoriety. She deflects the conversation to the outstanding community of potters in Montana, talking about how the state is one of four hotspots in the country for ceramic arts, and how the talent here is “through the roof.” The walls around her are lined with shelves, each brimming with cups and mugs made by different artists, a testament to time spent in the company of other potters.

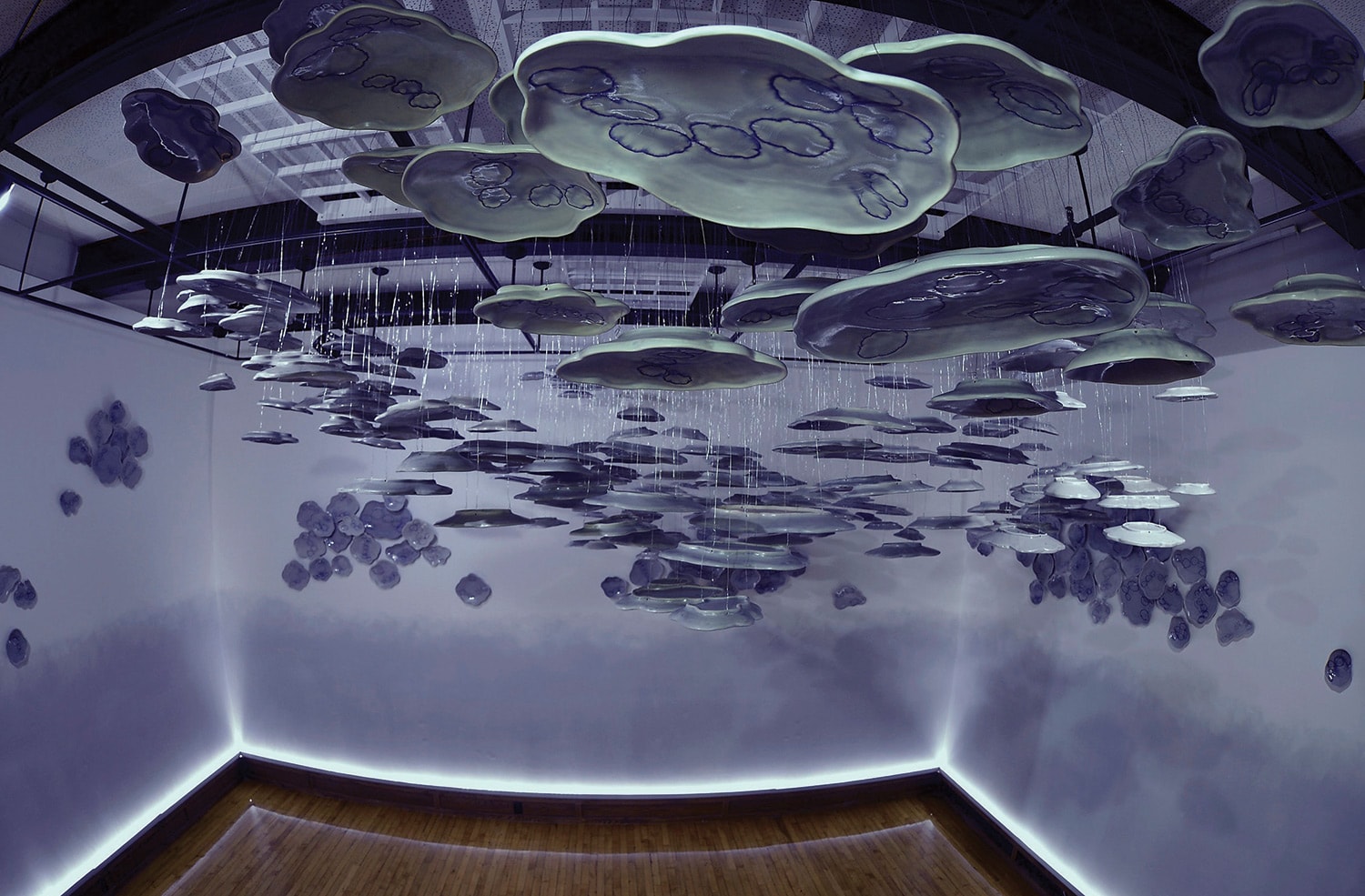

A cloud vase, part of a series of plates and vessels referencing Eastern Montana’s connection to agriculture and place.

But when asked about the major award she just received — a highly competitive $50,000 fellowship from United States Artists — she admits that the recognition is pretty exciting. And she was just as proud to receive the Distinguished Scholar Award this year from the University of Montana, which hadn’t been given to a professor of the arts since 1984 when it went to ceramics legend Rudy Autio. “That was almost as meaningful to me in the face of my peers,” she says. “When I received it, I said ‘Thank you for recognizing the arts.’ And the university president said, ‘No, thank you for all your work.’”

It’s the idea of service — to others and to the craft — that drives Galloway. She is the founder of Montana Clay, a valuable resource and virtual gathering place for the state’s community of potters. She created the Field Guide for Ceramic Artisans, a website packed with information for students who are transitioning from school into the world of professional pottery. She is a director-at-large for the National Council on Education for the Ceramic Arts, the largest group of ceramicists in the country. She opens up her home studio to wayward potters who need a place to work while they find studio space. It’s been her life’s work not just to teach the craft of pottery, but to bolster the reputation and understanding of ceramics, both in the fine arts world and by the general public — a ceramics ambassador of sorts, or perhaps an evangelist.

Just a few works from the “Endangered Species” series. The plates are coated in luster to act as a mirror to the viewer.

Just a few works from the “Endangered Species” series. The plates are coated in luster to act as a mirror to the viewer.

Even as she conceives and executes complex, highly technical, enormously time-consuming projects, she wants to make sure that her work is accessible, above all else. She’ll be the first to admit that ceramics can be a daunting medium to understand, even for someone well-versed in the arts, and not all ceramics are immediately inviting. “But my work,” she says, “you can look at it and pretty quickly feel good about it. It’s not hard. I always thought my job was like a little gateway drug.”

One way she accomplishes this is by making the abstractions in her work literal, such as the installation of “cloud plates” that she showed at the Paris Gibson Square Museum of Art in Great Falls, Montana. “Arranging the work in a way that supports the ideas helps the public understand the work. So hanging the plates that are shaped like clouds in cloud formations from the ceiling, then when you’re eating off of those plates, you’re clearly eating from the sky, which is what Eastern Montana is all about, with all that agriculture. It’s not a huge leap. People can get there.”

Galloway incises lines into a plate before applying inlay.

With its origins in the functional and utilitarian, ceramics has long grappled with something of an identity crisis: Is it craft or fine art? Can it be both? It’s this duality that often perplexes audiences. But, Galloway says, it doesn’t need to be that way. “I came up in the field during a time when we were really learning how to talk about pottery in a way that was not about technique, but about fine art critique,” Galloway recalls. “I could talk about pots in a way that was articulate, I could go mano-a-mano with a painter, and I wanted ceramics to be as important, which was about both ego and insecurity. I didn’t understand why this [holding up a cup] and a painting are so different. I said, ‘You have to explain that to me,’ and nobody could.”

That Galloway’s work deliberately functions both as craft and art is what makes it unique. “What she does so remarkably in terms of her [work] is that she squarely identifies as a potter, and embraces that, and has for a long time, even when it has not been very cool to be a potter,” says Jason Neal, co-owner of Radius Gallery in Missoula, Montana, which often shows Galloway’s work. “And she absolutely embraces that label, but she also elevates it — she’s the only potter I know who really thinks about bodies of work as installations in galleries and museums.” Her forms and technique — finely honed cups, pitchers, and other vessels thrown on the wheel — are very much those of a potter. But her decoration, alteration, and intent are all very much in the fine art camp.

A frog urn, also part of the “Endangered Species” series. Photo by Maggie Hamilton

Galloway is adept at creating carefully thought-out series that function individually as vessels, but viewed together tell a larger story. For example, a momentary, fanciful musing — what if drinking out of a cup with a bird painted on it allowed you to sing like that bird? — led to a massive installation: 1,400 cups, each one painted with a different North American bird, each on its own small shelf in a gallery. She affixed a motion sensor and small speaker to 75 of the shelves — when a cup was removed, the sound of that bird would play.

The scope of a project like this is what floors other potters. To hand-make and hand-paint that many cups is a mountain of a task, and it requires a fearless determination. David Tarullo, a ceramicist, installation artist, and former student of Galloway’s recalls being stunned by her productivity. “She makes graduate students look lazy, which is a tall task,” he recollects. “The amount of time and energy she puts in — it’s mind boggling.”

Out in her garage-turned-studio, Galloway’s current project is spread out across the counters in varying stages of completeness. In what is perhaps her most ambitious project yet, she is creating a series of urns and plates depicting all the extinct, endangered, threatened, and species of concern in North America — a list that numbers close to 2,000 and includes everything from grubs to birds to bears. The project, she predicts, will take about five years.

Sky Vault (The Cloud Room) references the connection between weather and food in agricultural regions like Eastern Montana. “We are eating from the sky,” says Galloway. Photo by Rios Sanders

Sky Vault (The Cloud Room) references the connection between weather and food in agricultural regions like Eastern Montana. “We are eating from the sky,” says Galloway. Photo by Rios Sanders

“I was walking through the Minneapolis airport, looking for my gate, half-listening to a podcast. And suddenly I tuned into what they were saying, and it was about the wandering albatross, which has a wingspan of 11 feet, and can stay aloft for a month,” she says. “And they’re having a hard time, because of commercial fishing. They are being decapitated at a rate of one every five minutes. And I heard that and it just went straight into my heart. … I just realized right then that I had to do something.”

She knew she wasn’t going to go join Greenpeace or become an activist directly on behalf of the albatross. “But I thought maybe I could make a difference using pots,” she recalls. Inspired by the scope and gravity of the AIDS Memorial Quilt project that she saw in person in the late 1980s, she decided to tackle endangered and threatened species in the same way: to create an installation of such massive proportions that it can’t help but command notice. Because, she says, one of the major successes of the AIDS project was that it lent visibility to a previously invisible problem.

“My goal is to make it personal, and to give people an idea of what they can do,” she says. Plates depicting state-listed species will be shown at galleries in that state. On the back of each, there will be information about the animal and what local action can be taken to help slow the species’ decline. Notably, the plates are painted with luster, turning each one into a mirror: Galloway wants audiences to see themselves reflected in these creatures and their fates.

Known as the “godmother of Montana ceramics,” Galloway has devoted her life to creating and teaching pottery. Photo by Maggie Hamilton

The urns, mostly for nationally listed species, will be displayed all together. The size of each is determined by the mass of ashes that would result from that individual animal’s cremation: A woodpecker will have a small urn, a bear’s urn will be nearly 3 feet tall. Most importantly, though, the urns will be empty. “Because,” she says, “they aren’t [all] extinct yet. In that emptiness is hope.”

Undoubtedly, what’s most striking about Galloway is her sheer, unshakeable devotion to her artistic vision, the medium itself, and the ceramics community. “There are plenty of artists in this world that commit to their work with that kind of fervor, that it’s literally an addiction,” Tarullo says. “But I don’t know of anyone else who’s taken on the kind of call for education and promotion of a medium with that same fervor. She’s so, so above and beyond.” He recalls asking how she decided to commit so completely to ceramics, and her reply was straightforward: “Well, I just decided ceramics was the thing for me, and I realized that there was a lot of work to do, and I’d better get busy.”

And she certainly did get busy. But she’ll be the first to say that she’s just getting started, and there are still so many more pots to make, students to teach, gallery talks to give, ideas to pursue, techniques to learn. “It’s a narrow road,” she says, “But it’s a very, very long road.”

No Comments