09 Aug Carrie Ballantyne

IF YOU HAPPEN TO BE AMBLING in the vicinity of Wyoming Blue Eyes, the painting by representational artist Carrie Ballantyne, prepare for a double take. The oil depicts a young woman whose wavy blond hair spills from a loose braid below a flat-topped, wide-brimmed hat. By itself, the piece is flawless. Yet what arrests the viewer is the young woman’s gaze, which appears to be directed outward, but also acts as a mirror reflecting the subject’s interior.

“Jessie on the Houlihan Ranch” | Oil | 20 x 14.5 inches

Ballantyne, whose works are in the permanent collections of museums such as the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming, the Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles, California, and the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, has been perfecting her skills since childhood. She is not producing portraits to mark a spot, chronicle a chapter in history, or make a statement about anything other than those traits that spring eternal.

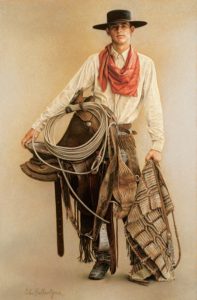

The Wyoming-based artist aims to reveal the essence of the figure before her, and it is that component of the interior contrasted with a formal exterior that defines Ballantyne’s work and adds to its intensity. Her figures are almost exclusively Western, and there is a timeless quality to the buckaroos, ranchers, cowgirls, and others who come alive under her ministrations; they represent a period-less American West. “I want them to look as though they could walk out of any era,” she said. “And our styles don’t really change that much within the ranching and cowboy culture.”

“Great Basin Buckaroo” | Colored Pencil | 26 x 17 inches

The Brinton Museum in Big Horn, Wyoming, recently featured a retrospective of Ballantyne’s work. The show’s title, Carrie Ballantyne Comes Home, referred to the fact that the artist lives in the Big Horn Mountains, near the museum that is dedicated to Western and American Indian art and culture. Brinton Director and Chief Curator Kenneth Schuster said Ballantyne, working in the tradition of observed realism, brings an unerring eye and inspired hand to each drawing or painting. “One of her many talents is that she has the ability to transcend the moment and take her subject matter to the next level,” he said. “In that respect, it’s not just about Western art or the landscape or the background. Instead, it’s what’s going on in that person’s mind or life; it’s the answer to the question, ‘What are they about?’”

Ballantyne’s earliest memories are of drawing the world around her and the figures in it. “I was drawing from life from the beginning — people I knew or was related to, cats, dogs, horses,” she said.

The turning point in her career, which has included work with dude ranchers and outfitters in Wyoming, came when Ballantyne was introduced to acclaimed cowboy artist James Bama, who became a cherished friend, mentor, and supporter. She modeled for him in a role she knew well — camp cook — and he, in turn, helped her hone her photographic abilities and critiqued her subsequent sketches.

She said of the artist, whose portraiture is celebrated for depicting Western and Native American figures in detail and with accuracy, “He knew the time he was investing in me was not a waste, that I was serious. It was very generous of him, and a treasure to me to experience that influence. It was the type of schooling that fit me, a much more organic approach.”

“Hannah’ s World — Sagebrush and Silk” | Oil | 21 x 22.5 inches

“Hannah’ s World — Sagebrush and Silk” | Oil | 21 x 22.5 inches

Like Bama, Ballantyne is seeking a certain look that she augments by using apparel and gear in which the design and function are shaped by the work to be undertaken. The habit of fashioning a visual feast is in play in Wyoming Blue Eyes, which came to life in a serendipitous way. When Ballantyne happened to be on-hand in her hometown of Sheridan, Wyoming, this girl stopped in at her mother’s shop. “I knew immediately she was someone I wanted to portray,” Ballantyne said.

“In the Traditions of her Father” | Conte | 20 x 13 inches

Ballantyne brings to life, in a layered fashion, the images of friends, neighbors, and family members. The painting In the Traditions of Her Father features Ballantyne’s daughter in fringed leather leggings astride a horse, vaquero saddle and coiled rope contending for attention, with the rider’s head half-turned toward the viewer, her visage inscrutable. An observer has the sense that the subject is soon to shift in the saddle, and her demeanor will alter to match a different mood. It is this quality that distinguishes Ballantyne’s work: Her figures appear to live, breathe, and think independently.

The artist isn’t sorting and counting, but she is aware that a good share of her models are women in a genre that generally allots more canvas space to men. But that isn’t her central point. “I’m trying to capture the beauty of other human beings,” she said.

“Rifleman” | Conte and Charcoal | 22 x 14.25 inches

Rifleman, a portrait of a ruggedly handsome man in Western attire with a rifle casually balanced on his shoulder, personifies what Ballantyne refers to as “confident masculinity” in her quest to portray an authentic attractiveness that is more than skin deep.

Ballantyne is represented by Legacy Gallery in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, and Scottsdale, Arizona, where co-owner Brad Richardson said the artist excels at realism yet avoids the error of succumbing to photorealism. “Her work has beautiful soft edges and a harmony of colors,” he said. “Some artists working from photographs produce pieces that are rendered like photographs. Carrie is different. Her paintings have heart and soul.”

For her part, Ballantyne relies heavily on instinct and intuition. “I still paint and draw by my gut instead of a formula,” she said. Even so, Ballantyne is a stickler for beginning with design. “Composition comes first and all else — whether it’s colors or values — follows,” she said of works executed in everything from oil paint to graphite.

The retrospective at the Brinton, which included new pieces as well as works on loan from other museums and private collections, brought Ballantyne full circle. “I’m generally fortunate in that most of my subjects are people I know,” she said. “Some of these portraits were shipped off years ago, and I never thought I would see them again; it’s like a family reunion.”

No Comments