09 Aug Outside: The Great Porcupine Mystery

Like most family photo albums, mine contains pictures of me as a child sitting next to roadkill. Now, before you dismiss this as just another small-boy-hangs-out-with-dead-animals-found-on-random-roadsides piece of nostalgia, let me boast about one particular photo, in which 4-year-old me, uncertainly holding a banana, is seated next to a substantial porcupine with perfect posture. I must ask: Do you have photos of yourself on your childhood deck commiserating with a porcupine that’s larger than you are? If so, perhaps we’ve encountered each other at the same group therapy sessions.

Much of the photo, surprisingly, can be explained, although questions regarding the banana remain unresolved. I would like to think I intended to share it with my prickly pal, but my eyes seem skeptical, understandably so. How is a boy to know whether porcupines even like bananas? Moreover, I imagine another inquiry plagued me, something along the lines of, Why the hell am I sitting next to a huge dead porcupine?

If you know my father, Parks Reece, an artist and my collaborator on this column, the question answers itself. If you don’t know him, suffice it to say that due to a combination of an unrelenting artistic calling and a mind that reflexively, without hesitation, always answers that calling, it likely never occurred to him to not throw the armored rodent into his car and take it home to pose his son next to it. The great muse is mysterious and beholden to no one and nothing, certainly not logic or parenting manuals.

All of which brings me to a deeper mystery, one with more urgent, big-picture implications: that of the disappearing porcupine, an ecological conundrum currently confounding biologists in Montana, particularly west of the Continental Divide and at high elevations. Part of my concern is motivated by greed: My son is almost 2 years old, entering his prime porcupine-posing age, and the chances of me passing along this sacred family photography tradition seem increasingly slim. But the greater worry is that in my lifetime, I may witness yet another wild creature finding its existence in question, or at least a local population vanishing from my backyard. I shudder to think what animals will be left for my own son to one day place next to his frightened children for photographs. Domesticated squirrels? Pigeons too fattened up on human refuse to fly away? I don’t expect everyone to care about porcupines, but if we think matters such as extinction and the health of wild beings are important, then this quandary means something.

In a 2017 newspaper article, Germaine White, an education specialist with the Confederated Salish and Kootenai tribes, called the porcupine conundrum “one of the great ecological mysteries.” Sightings on the Flathead reservation, like other places in Western Montana, once were common but are nearly nonexistent nowadays, and the tribes are among the entities devoting resources to solving the mystery, sending biologists into the field to investigate. Other researchers in Montana have also been on the case, but the efforts have rendered more theories than answers. The animals are disappearing elsewhere in the West as well.

Like other wild animals, the presence of porcupines on the landscape has long been tenuous due to human aggression, although it wasn’t always that way. Many Native Americans revered porcupines for both spiritual and practical reasons — namely, the slow-footed creatures, which rely on quilled protection, were an easy food supply in times of scarcity, according to naturalist Ellen Horowitz’s 2015 article in Montana Outdoors. Early white settlers also understood that porcupines were handy in emergencies. Killing one without eating it was considered bad luck, and not very prudent in an age before ubiquitous supermarkets.

But once the U.S. Forest Service began planting trees to replace those removed by logging and wildfire in the 1930s, the animals ran afoul of humans, as Horowitz detailed. Porcupines are nocturnal herbivores that feed on woody shrubs and trees, and they ate the Forest Service’s newly-planted saplings. The federal government launched eradication programs, including the placement of strychnine-laced salt blocks in national forests, until the practice was banned in the early 1970s.

The word “porcupine” comes from the Latin porcus, which means pig, and spina, which means spine or quill. Their 30,000 or so quills, which are modified hairs, are their main line of defense, as they possess neither speed nor wolverine-like fighting instincts, perhaps explaining their absence from the X-Men lineup. They can, however, whip their tail at lightning-quick speeds.

Because of that defense system, they have few natural predators. One exception is the mountain lion, which has learned to use its paws to flip them onto their backs and eat their exposed underbelly. It’s a hearty meal, as porcupines can tip the scales at more than 30 pounds, making them the second biggest rodent in North America behind beavers. But there’s no evidence that mountain lions have suddenly gone on unprecedented porcupine killing sprees, and even at a steady clip they couldn’t single-handedly bring a population close to extirpation.

Humans remain a dangerous nemesis. Though the poky pigs are docile, when they feel cornered, they have a tendency to implant their quills in curious dogs’ noses, which is why pet owners and bird hunters are known to kill them. Nursery farm operators do as well, for the same reasons that Forest Service officials did long ago, as do any number of other people who decide that taking the animals’ lives is better than dealing with their perceived nuisance. Still other porcupines, like my picture partner, are killed unintentionally on roads.

Biologists say another potential culprit is climate change, which may impact porcupines’ habitat and the trees they eat, through more severe and prolonged fire seasons and mountain beetle infestations. An unknown disease could also be wiping them out. Then there’s the fact that they only produce one to two babies per year, wonderfully called “porcupettes,” so any disruption to the population is hard to overcome.

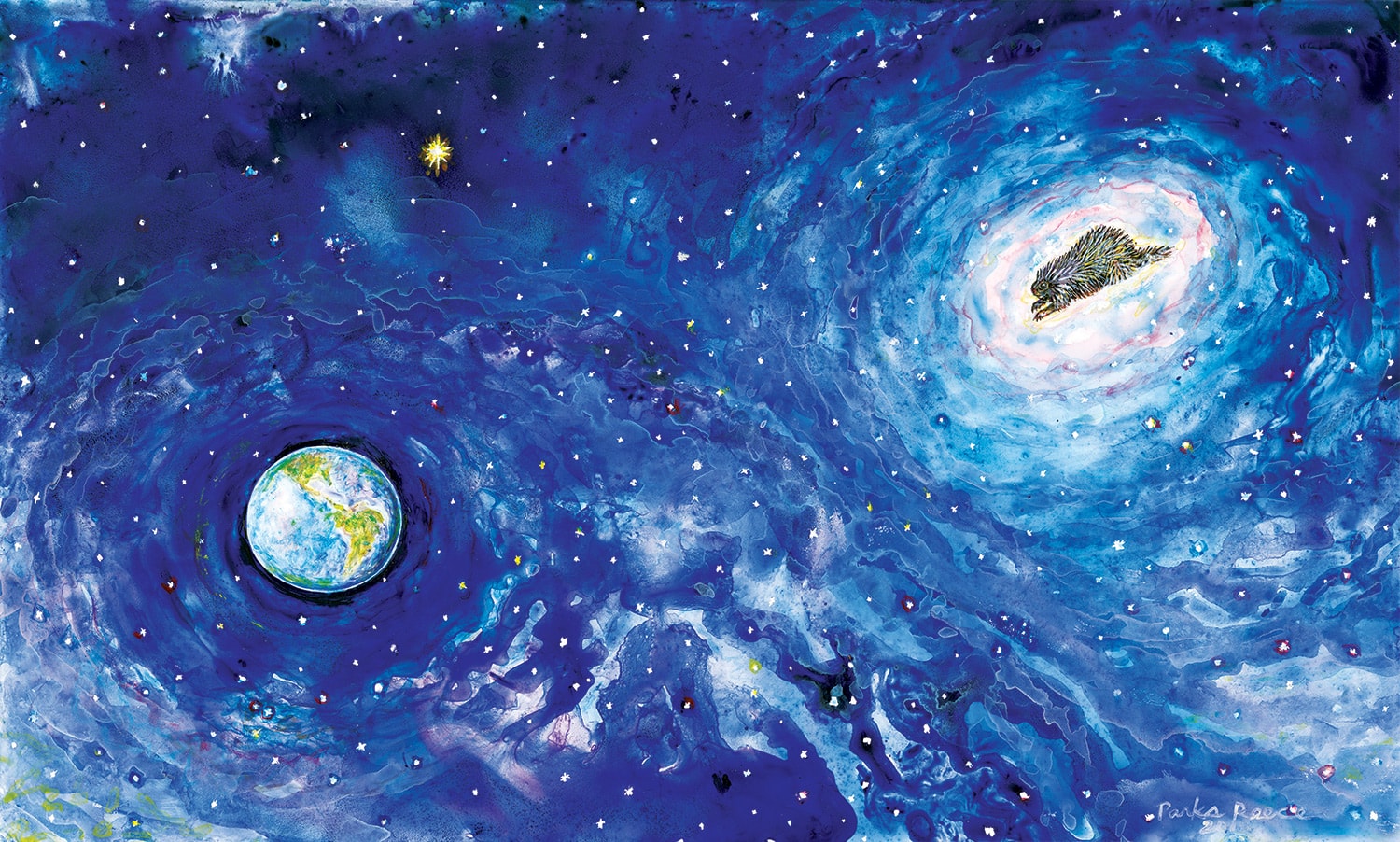

One of my father’s paintings posits a theory that, to my knowledge, biologists haven’t yet explored. It suggests that porcupines have relocated to outer space. Given that biologists operate in the realm of science and not art, I’m sure they’d have to see more conclusive evidence than a colorful acrylic painting before sending researchers off in spaceships. I imagine it would also be difficult to secure the funding.

But I like the idea. Think about it: Porcupines are floating out there among worlds unknown, safe from mountain lions and disease, beyond the reach of human bullets and poison: a billion quills joining a billion stars outside the bounds of imagination (except for an artist’s). Wherever they are, I only ask for one to make its way back into my orbit, because I have a camera and a small boy waiting. I’ll even make sure to bring a banana.

No Comments