07 Jun Images of the West: Leaving a Legacy

Perhaps it’s ironic that within the wide-ranging photography of Julia Tuell, one of my favorite images was not snapped by Tuell herself, but by her husband. By Tuell’s standards, the photo might have seemed haphazard, and her rather serious expression suggests she worried about whether her husband could manipulate the shutter correctly. But this casual grouping of Tuell with her daughters, Wenonah and Julia Mae, and her baby, Carl, held by the Cheyenne Chief American Horse, speaks volumes about the relationship of a remarkable woman to the Native American people who were her friends and photographic subjects for much of her adult life.

Julia Tuell, her daughters Wenonah and Julia Mae, and her baby son, Carl, with Cheyenne Chief American Horse.

The two little girls who squint against the sun in this photo may know that the man behind them fought against George Armstrong Custer on that terrible Sunday in 1876, but if so, that fact means little to them. They know American Horse as a grandfatherly man who stops often to have coffee with their parents. And one suspects this isn’t the first occasion on which the chief has held their baby brother.

The trail that brought a young mother to the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation in the early 20th century tells a story that brims with determination and zest for adventure. Julia Toops married a retiring Indiana school teacher at age 16 (he was over 40) in a union that would be considered beyond scandalous today, but then was likely considered a match that would grant her a steady provider. Yet, everything I’ve gleaned from her life story and the family history related to me by her youngest son, the late Varble Tuell, suggests she was after anything but security. She wanted adventure. A teacher retiring from the Indiana educational system so that he could pursue a second career within the reservation educational system offered, among all else, a ticket to exotic and exciting places.

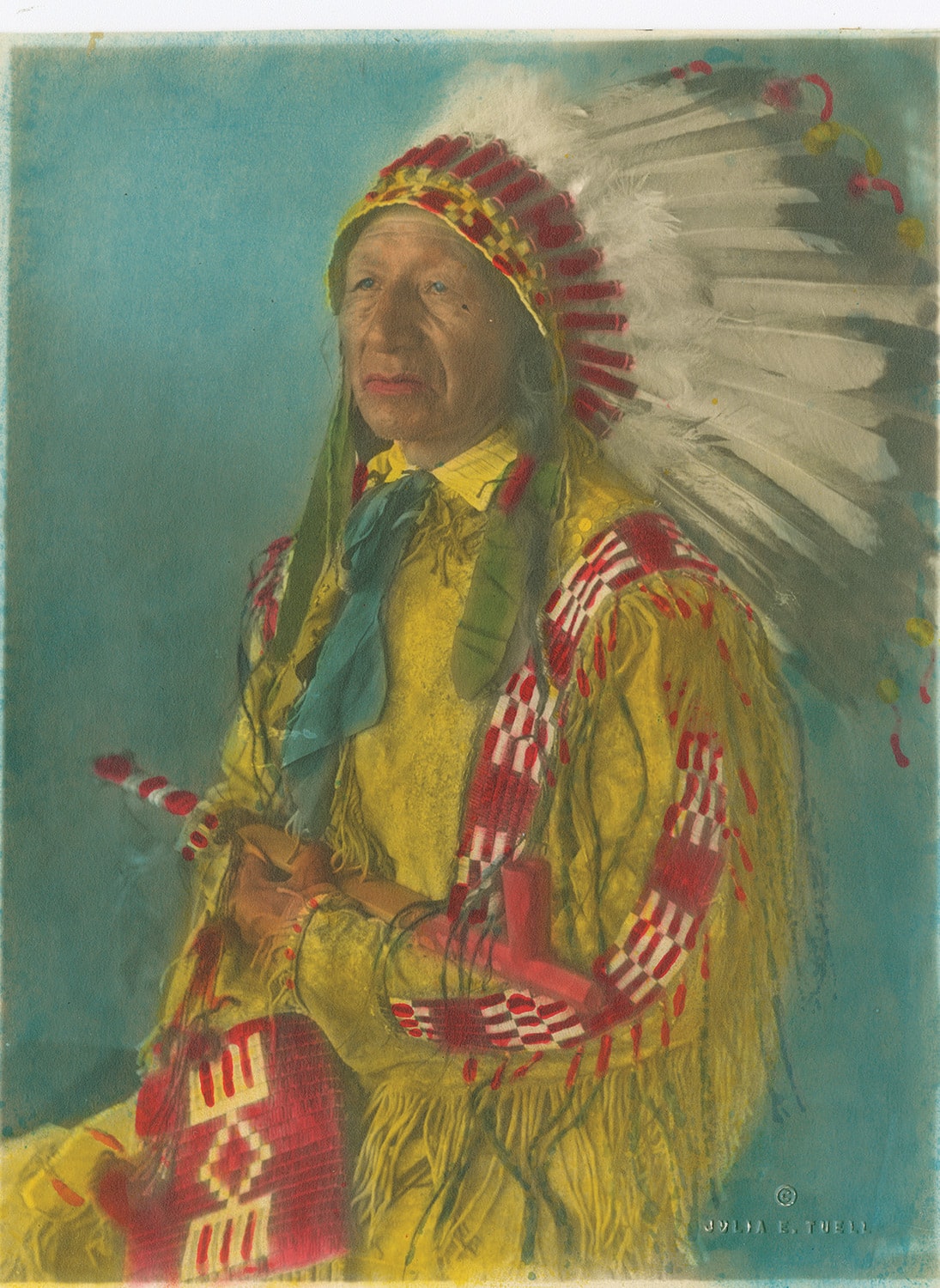

Chief American Horse of the Northern Cheyenne, veteran of both the Battle of the Rosebud and Battle of the Little Bighorn, taught Tuell the Cheyenne language and worked to lift the U.S. government’s ban on the Sun Dance.

Tuell had no camera during her first couple of duty stations. They started out with the Chippewa in northern Minnesota, where during the first winter, on a night that was 50 below zero, she gave birth to her first baby, Wenonah. The second reservation was with the Sisseton Sioux in eastern South Dakota. Although her photography career would not materialize until the couple moved to the Northern Cheyenne reservation in Montana in 1906, perhaps her experiences at the earlier locations alerted Tuell to the great human drama that was passing before her eyes like a fleeting Western autumn, soon to be gone. The free-ranging lifestyle of Native Americans was history. Many of their dances and religious rituals were outlawed. But the people and their stories were still alive, and their customs were still being practiced. And the Cheyenne past was still vivid. Any member of the tribe older than 30 when the Tuells arrived in Lame Deer, Montana, had lived during the era preceding the Custer fight.

Family lore has it that the camera, an Eastman Kodak 8-by-10 glass plate model, came to Tuell via mail order. Roll film was already in wide use, so her camera was by no means state of the art. She made contact prints by holding the plate in its frame facing a kerosene lamp, timing the exposure with a windup alarm clock. In later years, her memory of color still sharp, she hand-tinted some of her creations.

In 1912, the Tuell family was transferred to Oklahoma to teach the children of the Sac and Fox tribe. The climate of the area was not to their liking, and they missed the sight of snow-capped mountains on the horizon. As the Northern Cheyenne had once done, they fought their way back north, to pine coulees and the scent of sage. Their battle was far less painful, of course, and consisted of wading through government bureaucracy rather than skirmishing with government troops. But their quest eventually landed the family with the Sioux on the Rosebud Indian Reservation in south-central South Dakota. There, the photography continued.

Strong Left Hand (on horse) lost her first husband, a Northern Cheyenne warrior, in the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

Strong Left Hand (on horse) lost her first husband, a Northern Cheyenne warrior, in the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

In the early 1990s, my college teaching aspirations deflected by my desire to return to the family ranch, I taught English and social studies at the high school in Bridger, Montana, where Varble, Tuell’s youngest son, semi-retired, held a custodial job. Often he stopped by my classroom with tales of his childhood and particularly of his mother, whom he adored. And always the conversation landed on her many remarkable photographs.

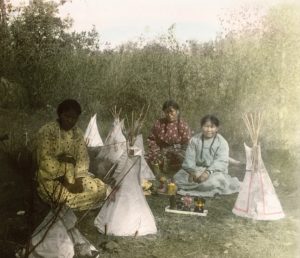

Cheyenne children at play, 1907.

I was interested, but getting my full attention was tough for Varble. With a 120-mile round-trip drive each day from the ranch, a herd of cows at home, and a stack of papers to correct while teaching six classes at school, I was strung out and overworked. But Varble’s worries about his mother’s buried legacy came to a fever pitch when he discovered that a well-known Western artist was duplicating his mother’s portraits with only slight changes and no credit to her. Tuell’s photography also was appearing on postcards without attribution or, in some cases, incorrectly credited to another photographer. I’d written a couple of books at this time, and Varble was sure I could produce one that would stop the bleeding, fix his mother’s photographs under copyright, and give her the credit that was due.

Tuell entitled this photo of Blanch Roubideaux of the Rosebud Sioux “A Madonna of the Rosebud.” The photo has been incorrectly captioned elsewhere.

He got my attention. I entered my classroom one morning, flicked on the lights, and was greeted not with the room’s normal, drab interior, but with a museum. Ringing the room, mounted in Western-themed frames crafted by Varble himself, were stunning portraits of great chiefs, American Horse of the Sioux and his Cheyenne counterpart with the same name. Two Moons was there along with Woostah (White Cow), daughter of Morning Star (Dull Knife). There were children at play with toy tipis, the haunting beauty of a Cheyenne schoolgirl, the sad tears of a boy headed for school. A woman mourned at the foot of a tree in which her deceased child lay, wrapped in blankets on a platform of poles. I blinked. Then, during my prep period, I wrote a query letter to a New York editor and began planning for the book, Women and Warriors of the Plains: The Pioneer Photography of Julia E. Tuell.

There were, perhaps, photographers of the early reservation era whose work had a technical edge on that of Tuell. Some of them had better equipment, more resources, and the freedom to travel. But Tuell had a grasp for the important, for the very souls of her subjects. She didn’t limit herself to photographing chiefs in their regalia. Equally important to her were the women, the children, the daily tasks of a people undergoing the trauma of social and political upheaval, yet retaining their dignity and beauty. Nor did she flinch from the nitty gritty — she even documented the preparation of dogs for food.

Tuell’s youthful femininity opened doors as well, as did the trust of the Cheyenne and Sioux people who knew her. I believe that American Horse, who taught Julia the Cheyenne language, saw her as one who could be made to understand the crucial nature of their religious rituals and perhaps be of influence in restoring the people’s right to exercise them. His trust was no doubt the key that opened to her and her camera the most secret and sacred of Cheyenne religious rituals, the Massaum (or Animal Dance). Along with her friend George Bird Grinnell, she was permitted to witness portions of it. Later, her photographs were used by Grinnell in his work on the Cheyenne, and are the only visual record of this sacred ceremony. Indeed, in his writings, Father Peter John Powell believed, “Julia Tuell’s greatest legacy remains her capturing the mystery and power of the last great Massaum among the Northern Cheyenne people, that final offering of the holy ceremony where the animals dance, bringing blessing, healing, and renewed life to the Cheyenne people and their world.”

John Fast Horse, of the Rosebud Sioux, dressed in war shirt, 1913.

John Fast Horse, of the Rosebud Sioux, dressed in war shirt, 1913.

Tuell was in the right places at the right time, and she recognized that fact and made the most of it. But it was the sympathetic vibration between her and her subjects, the common humanity she shared with the Cheyenne and Sioux, that nudged through the limitations of glass plates exposed by the light of a kerosene lantern and left us a legacy.

Daniel A. Langston

Posted at 17:37h, 16 SeptemberI’m looking to collaborate with someone who knows Julia Tuells work.