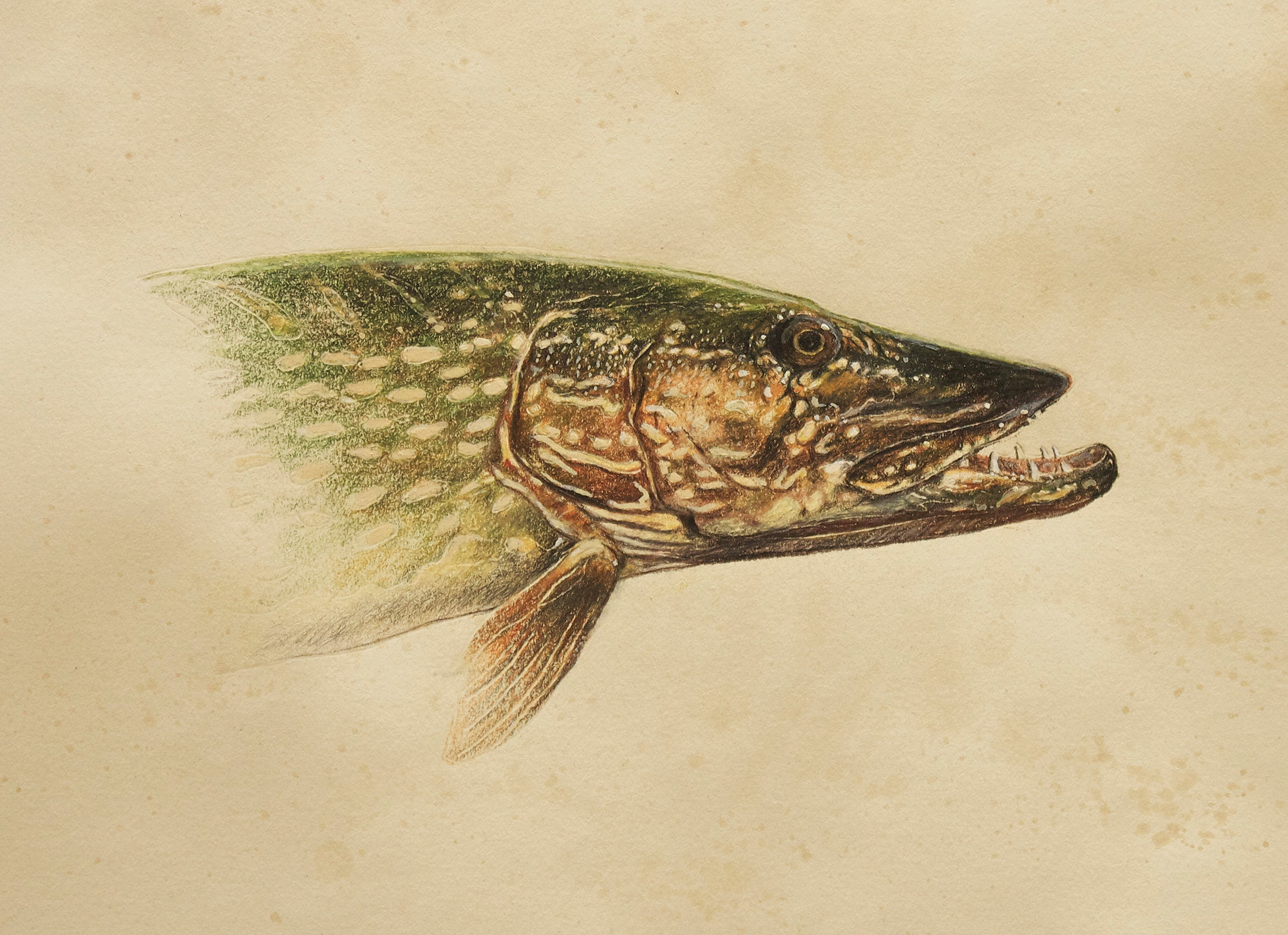

27 Nov Outside: Esox on the Fork

You really can’t blame the northern pike for living in Western Montana’s waterways; these fish simply rode in on the helping hands of anglers, decided they liked the scenery, and chose to stay.

If this sounds familiar, you may be thinking about our beloved non-native rainbow and brown trout, which gained access to our river systems back in the 1800s in nearly the same way. And if you look a little deeper, you might even see a little of yourself in the northern pike — most of us trace our presence in Big Sky Country to our relatives, who tossed caution to the wind and headed west for fertile grounds, no matter if they were welcome or not. And we’re still here.

To my mind, the northern pike (Esox lucius) is doing nothing more than we would: making a living and keeping its head mostly low. Still, in a state that values trout above almost all else, the northern pike isn’t well liked. That’s why it’s such a dilemma when I catch one of these fish, the question being: Should I release a big pike to fight again or whack it on the head to save a few rainbow and brown trout that this apex predator might eat if allowed to live?

I asked that very question in October while fishing the Clark Fork River outside of Missoula. Fall in Montana. Winter soon at the doorstep. New friends, Matt at the oars, Dave in the back. I was chucking an 8- or 9-inch-long tube fly that included a Mr. Twister-style, hand-painted tail. It felt like I was casting a Cornish game hen.

We didn’t expect to find any pike in the main river — these fish like slow, weedy water where they can ambush smaller fish. None of Western Montana’s large rivers harbor an immense amount of this habitat, but where it exists anglers usually find pike, if they specifically look for them. Most don’t because these same backwaters often hold some large trout.

The first backwater was perfect pike turf, deep where it met with the main river, quickly shallow and growing weedier and narrower as we moved up its length. Dave hooked and lost two pike that I’d cast over, making me wonder if these fish were picky. Matt said they usually weren’t, although he follows a European pike fishing reality show that says northerns can be demanding, depending on as many factors as those that influence a trout to eat, including temperature, wind direction, water levels, and barometric pressure, to name only a few.

By the time we reached the end of the slough, I had traded seats with Matt and was rowing us slowly toward the mouth. Along the way, Matt picked up two small pike and Dave caught one also, all hammer-handles, which is the pike fisher’s pet name for young fish that are long and skinny.

To be a good pike fisher in Western Montana requires focus — meaning you have to ignore scads of trout rising to mayflies and caddis on the main river, and just row downstream from one slough to another. That’s what we did. But by midafternoon we still hadn’t caught any large pike. Then we anchored the boat on the river side of a peninsula, per Matt’s request.

“I’ve heard of a 38-incher coming out of this slough and I’ve lost a couple in here that may have been bigger,” he warned. “I don’t want to scare these fish with the boat. So let’s fish it from the bank.”

We hiked over the gravel and Dave headed for the top of the slough to look for trout. Matt walked to the bottom of the slough where it joined with the river. I walked straight ahead and arrived at what I thought to be a perfect place, right where the weediest part of the slough gave way to deeper water.

I hooked up on my first cast and as this pike, maybe a 6- or 7-pounder, raced toward deep water, another pike of equal size followed it. When I landed the pike, we shot some photos and then asked the tough question: Should we kill it? The fish slipped out of Matt’s hand before we had to make a decision.

After a couple high fives, Matt wandered back to the mouth. I cleaned off the fly, and cast again. Earlier, I’d retrieved the fly quickly, but now I let it sink deep. I gave it two quick strips and then a long, slow pull. And almost immediately a fish grabbed the fly. At first it didn’t move and I wondered if I’d hooked something secured to the bottom, perhaps the shopping cart, the old tire, or the full keg that we’d seen in one slough, all deployed from a steep bank and a dirt road above. I pictured big-time teen entertainment on a Friday night.

Seconds later, however, the fish raced to the opposite bank, and then downstream toward Matt. It sulked out there for a minute or two until I could crank it toward shore where Matt waited with a long-handled net.

I’ve caught pike in the Yukon Territory and northern Manitoba, and even a few hammer-handles in Alaska, but I couldn’t tell Matt how big this fish might be. I knew this: It was a giant fish for the Clark Fork River, just 15 minutes away from my home, and I was thrilled to have it on the end of my line. Ten pounds? Twenty pounds? More?

When the fish slid into the net, Matt and I whooped. When we stretched a tape along the fish it measured 35 inches. When Matt hung it from his digital scale it read 13.5 pounds. When Matt asked me what I wanted to do with it, I said, “I’d prefer to let it go.” And that’s just what we did. After shooting a few pictures, Matt let the fish slide out of his hands and back into the Clark Fork.

So, was that the right thing to do? When I texted a photo of that fish to a trout-addicted friend of mine he texted back, “Dead, I hope. Tasty.”

When I texted, “Alive. You can’t eat them,” he replied, “What? You let it go?”

I texted, “Yeah. I’ll catch it again.”

He replied, “After it eats 37 trout.”

I lied and typed, “They only eat suckers and whitefish.”

He texted, “And Five Guys burgers and children. That thing should have died.”

Should it have? I decided to find out. So, a few days later I called biologist Ladd Knotek at Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks, and described the situation to him.

He explained that the department can’t tell anglers exactly what to do when they land a northern pike in Western Montana. That’s because the department doesn’t recommend eating pike from certain places, including the area we fished that day, due to health risks these fish pose to humans. In the Clark Fork and other places, mature pike accumulate dangerous levels of toxins.

“It’s a conundrum,” Knotek admitted. “On the one hand we’d like to see anglers harvesting these fish, but you can’t eat some of them and it’s illegal to waste a gamefish in Montana … so you have to let them go.

“If you want to eat pike, the way to approach it is to fish for them where there aren’t advisories,” Knotek said. “And no matter where you fish for them, whether in the Bitterroot or the Clearwater or the Clark Fork, you just have to be smart about it — you do not want to eat a 10-pound fish that has accumulated contaminants over time. You want a younger, smaller fish.”

Despite it being illegal to waste gamefish in Montana, it’s my guess and an occasional observation that pike don’t get many second chances. Take that day on the Clark Fork when we encountered a couple anglers fishing backwaters specifically for pike and celebrating their success by swinging those fish into the boat and whacking their heads.

Noticing us, one of them said, clearly defending himself, “Just doing our river cleanup today.” He added, “There are a couple guys on the bank below with a stringer of trout who will probably be happy to eat these fish, too.”

And if not?

Now that I know what swims in the backwaters, I’ll probably always drift the Clark Fork and Bitterroot with a 7- or 8-weight rod rigged up for pike. I won’t dedicate a majority of time to fish for them because I, too, like the challenge of taking trout on dry flies, especially on technical, flat-surfaced rivers like the Clark Fork and Bitterroot. But hooking into a fish weighing 10 pounds or more is a certain thrill, whether that fish is a Montana native or not. And I’m already looking forward to taking my daughters on a spring pike float when the water is warm and those fish may take surface flies, such as mice imitations and poppers. And when we let those fish go, I’m not going to feel one bit guilty. The truth is, at least in the Clark Fork, northern pike aren’t decimating trout populations and Knotek doesn’t think that harvesting them would make much difference anyway.

“The pike are here to stay,” Knotek said. “But they are found in low densities on the Clark Fork and are not a big factor on trout. Instead of focusing on pike, we look at the bigger picture for trout. Are we getting good recruitment? Do these river sections offer trout populations similar to historic levels? And the answer is yes.

“Pike may be influencing trout populations in the lower Bitterroot where there are lots of backwaters and sloughs, but it would be a stretch to say that, even there, we could manage pike through harvest,” Knotek added. “Pike populations go up and down depending on the water conditions when they spawn in the spring. We can’t really do much about it.”

So the next time you’re on the Clark Fork or Bitterroot, and you catch a 10-pound-plus fish that could make an angler’s season, you may take a moment before you whack it on the head and choose, instead, to let it go.

No Comments