12 Aug Three Paintings: The Themes of Clyde Aspevig

Try this one on for size: One measure of an artist can be found in how well he or she teaches us to see, how well their particular vision informs our own. Van Gogh’s starry skies. Modigliani’s nudes. Hokusai’s wave. Just try to look at a pond lily and not think, Monet. It’s a matter not just of technical skill but of sensibility. Ideas should inform a given work quite as much as an artist’s palette or technique. A good painting arises out of the marriage of pigment and canvas, sure; the fabled 10,000 hours at the easel. But it also comes out of the books you’ve read, the good conversations you’ve had, the excellent bottles of wine you’ve shared.

To all appearances, Clyde Aspevig — one of the most collectible artists in America — spends the bulk of his days squeezing tubes of paint onto a board, dipping a brush, touching it to canvas. Stepping back, reconsidering, repeating. He’s painting. But more, he’s exploring his next idea. He’s giving us something to chew over. Then something else. And something else again. It’s an invitation to a dialogue. And it’s heavy lifting, the push and pull of ideas against plastic reality, originality versus imitation, diligence against self-indulgence. Part of the art lies in making it look easy.

“Winter Vibrations” | Oil on Linen | 48 x 48 inches

“Winter Vibrations” | Oil on Linen | 48 x 48 inches

Catch him at a quiet moment, Aspevig is also exceptionally thoughtful about his work, generous about walking you through his process. Why this way and not some other? His new studio just outside of Bozeman, Montana, lends itself to browsing. With his most recent works arrayed in a sequence, one piece after the other, it’s easy to note certain continuing themes.

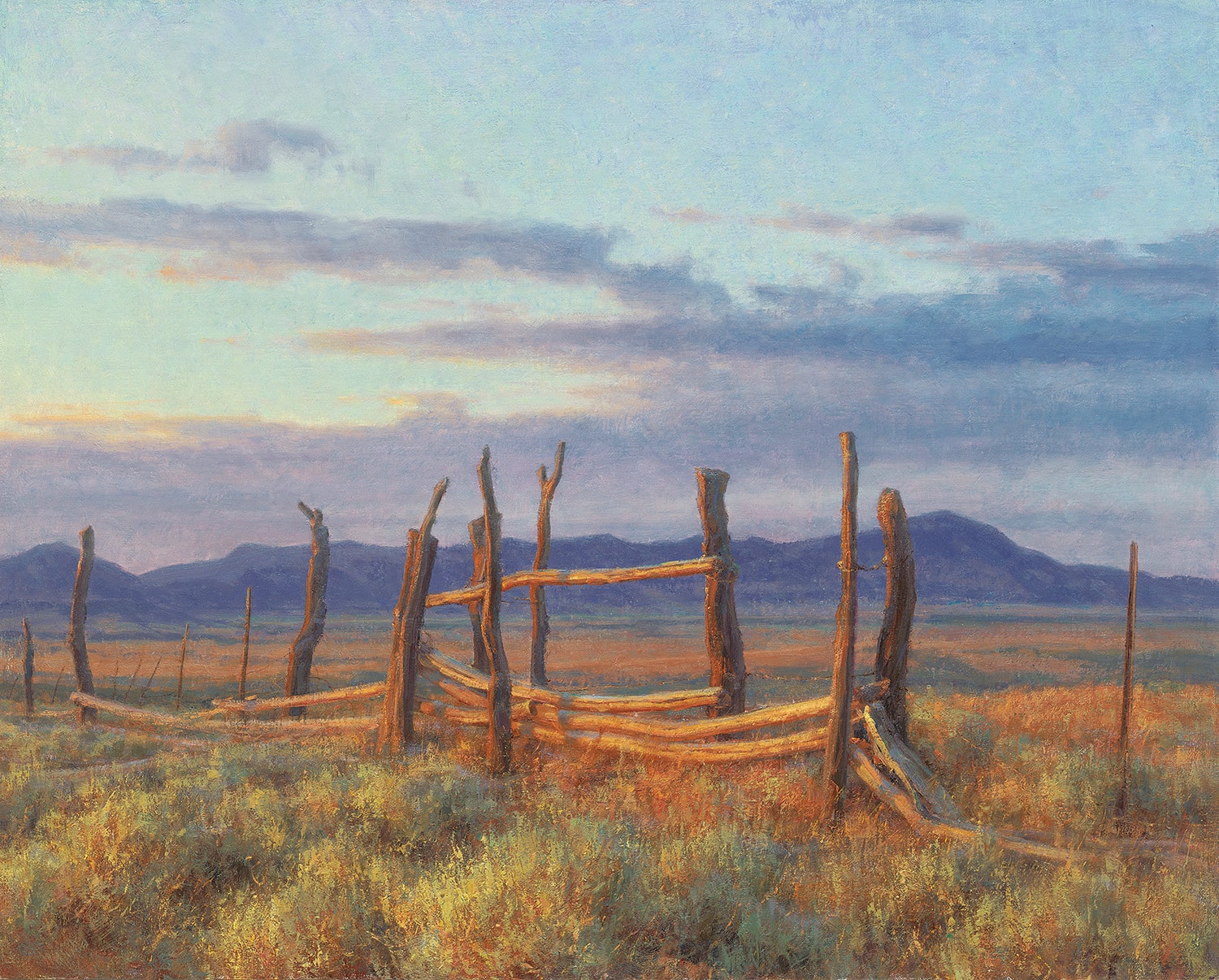

Most of his work, for instance, clearly arrives into the moment with an undercurrent of narrative. Stories. Subtext. “I decided to call this one In the Hands of Time,” he said recently, standing in front of a study of a fence in Eastern Montana. “These cedar posts represent the ranchers I grew up with. All those characters that have been trying to hold up their fences.” He paused, considering. “But fences can represent so many things. Are they fencing the viewer in or out? And I wonder about where the posts came from. There’s no wood out there. Then I think about the amount of energy it took to build these in the first place. And then, of course, I think about how these posts will eventually fall into the ground. Nature takes us all in the end.”

Aspevig spent his childhood in Rudyard, Montana, on the Hi-Line. Wheat farms and wind, family and friends, and a rich, changeable light. “I had to invent my own reality.” It’s a background, later tempered by formal education and determined self-training, that would lend itself to a certain kind of contemplation. About the fenceposts, he continued, “By breaking the horizon I created tension in the painting. I played with scale. Then if you follow the fence, there’s the metal fence post, and if you know this topography, there’s a glimpse of the Zortman mine.” An open pit gold mine in the Little Rockies, and a scar on the landscape. “If you look at the texture, I’m dragging my brush to create these vibrations and fractals. In my opinion, that makes them more real. The brain fills in the rest. The fence posts are whole notes, half notes, quarter notes. How you arrange the shapes creates a rhythm. Our response is innate. Subliminally, the mind is going to accept it.”

Further down the wall, Aspevig’s painting Blooming Sage, finished in the winter of 2015, dwells less on narrative and more on a specific tension between realism and symbolism. “By trying to create the symbols of things, my paintings begin to take on more realism.”

Aspevig and his wife, the acclaimed artist Carol Guzman, are proponents of an idea they call “landsnorkeling.” It’s a notion that describes the act of submerging yourself in the landscape, walking and exploring with no destination in mind save, perhaps, your own awe. “This was one of those landsnorkeling ideas. I wanted to do a portrait of life-sized blooming sage. And it ended up being a challenging painting. How do I deal with the texture of the sagebrush? How do I get the nuance of it, the feeling of it? The tensile strength when it blows in the wind and moves back and forth? I tried to accomplish it partly through a hierarchical system. Shapes and patterns. Some are less dominant than others. That hierarchy allows the eye to navigate through a complex painting, and be able to land on certain spots. It was a painting that really forced me to orchestrate things.”

I asked him if he worked these issues out ahead of time or did it on the canvas.

“In this particular one, I worked things through on the canvas. You plan out a painting and you think you’ve got it. But then you get involved in it, and it just kicks your ass. You have to work through it. It’s like that old Mike Tyson quote, ‘Everybody has a plan ‘til they get punched in the mouth.’”

“Blooming Sage” | Oil on Linen | 40 x 60 inches

“Blooming Sage” | Oil on Linen | 40 x 60 inches

He stepped closer to the painting. “I love the smell of sage, it’s one of my favorite plants. I started out looking for ways to include a sage grouse in there, but it just didn’t work. But there’s a suggestion of a pathway from the lower right corner. You can find your way through.”

Past a floor-to-ceiling bookshelf (“This is the first time we’ve had the bulk of our books together in one place.”), Aspevig’s workstation faces east, with good light from two windows. At any given time, he’ll be rotating through three or four pieces, one to the other. A completed painting, Winter Vibrations, faced his easel.

Aspevig’s landscapes, insofar as they’re representational, are meant to be accessible. “It’s one of the reasons I love landscapes. They’re concerned with what I call the stage, the mantle of the earth itself. The stage that we act out our lives on. It’s the stage where all of our emotions and experiences in life take place.” But he also wants his art to offer more. Once a viewer is familiar with a given piece, if they’re interested in looking deeper, he feels that it should be available to them. “I wanted Winter Vibrations to explore the idea of echoes. In this particular one, I was using tons of texture. And I was scratching things out with different tools to create movement. A sense of energy. The layers of paint build up a visual complexity. When you go up and look at it closely, it has all kinds of what I call fractal worlds within it. It looks chaotic, but then it begins to organize in certain ways.”

Aspevig will typically work on three or four major paintings at any given time, rotating them on and off of his easel.

While specifically influenced by artists such as Emil Carlsen, John Singer Sargent, and El Anatsui, Aspevig’s reference points for his art are just as likely to be literary. He said, “I tell people, if you want to be a good painter, read philosophy.” He also said, “People ask me for the best book on art, I say it’s Your Brain on Music.” About Winter Vibrations, he added, “What I found as I got more and more into this painting was the universality of certain shapes. I was almost finished with it when I ran across a book called The Beautiful Brain, by the great Spanish neuroscientist Santiago Ramone y Cajal. He has these incredible drawings, these cross sections of different brains. Dendrites. And I’m looking at them and I’m seeing universal patterns.” Aspevig came to recognize similar patterns in his painting. “I think it gives the landscape a whole different dimension.”

He squinted at Winter Vibrations, choosing his words. “The real key is … I don’t expect people to come up to me and say, oh Clyde, I really enjoyed what you did with all these fractals. That’s not what I expect. But what it does for me as a painter, it makes me think about it in a different way. And then I begin to paint in a different way. Which broadens my ability to express myself.”

Toward the end of my time with Aspevig, he said, “We all stand on the shoulders of others. But each of my paintings is the only one of its kind in the world. It may be minuscule in the grand scheme of things, but it’s big in my life. Put it all together, it eventually translates into a productive human life.” He leaned back, considering his work from a slightly wider remove. “I recently turned 66, and the world is just starting to open up to me.”

No Comments