24 Aug Sweetwater in Wyoming

ROAMING FLY ANGLER SOMETIMES UNCOVER extraordinary places where history, geography and flowing water intertwine and illuminate each other. I’ve found a few such locales in my wanderings; Central Wyoming’s Independence Rock is among them, a granitic temple of profound convergences.

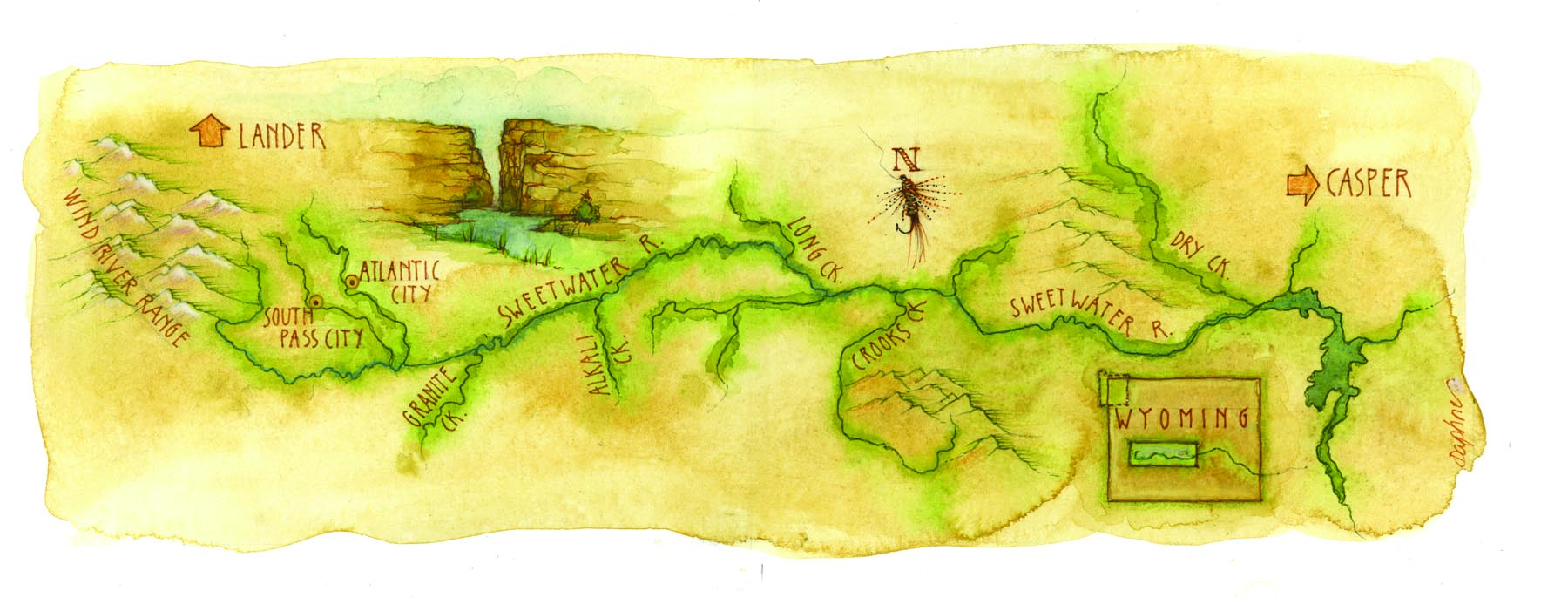

In sun-bleached August air I clambered up the steep incline. Once on top, my trip up the trout-rich Sweetwater River came into focus. The lower Sweetwater created a sinuous oasis in the broad desert valley, punctuated by isolated canyons. Sheltering the headwaters in the distant west, the 12,000-foot high, snow-blasted fangs of the Wind River Range appeared as impenetrable and forbidding as they did to 19th-century pioneers bumping along the Sweetwater in their covered wagons. North of the river, the jade and uranium-rich Granite Mountains framed a stark panorama that still excites prospectors. And along the south rim, the obscure and mysterious Green, Ferris and Seminoe mountains swept east toward the North Platte Valley, where the Sweetwater ends.

Thousands of travelers along the interlaced Oregon, California, Mormon and Pony Express trails etched their tracks in the earth and their names in Independence Rock, layered palimpsests for posterity. Known as the “Great Register of the Desert,” the rock served as both an enormous trailside cairn and a pre-Twitter bulletin board for prairie schooner pioneers, sometimes confirming that loved ones ahead of them had survived. One journeyman, William Anderson, recalled: “On the side of the rock names, dates and messages … are read and re-read with as much eagerness as if they were letters … from long absent friends … ” Similarly, sojourner Lydia Allen Rudd wrote, “July 5, 1852 — came to Independence Rock about ten o’clock this morning … I saw my husband’s name that he put on in 1849 … ”

To stay on schedule ahead of winter’s deadly bite, emigrants attempted to cover the 815 miles from St. Joseph, Mo., to the monolith by Independence Day, when well-deserved celebrations often erupted. Once they resumed their journey — averaging 15 miles a day and often more than 2,000 miles in total — migrants were soon greeted by two other iconic features I spotted upstream.

In the distance loomed Split Rock, visible for more than 50 miles, its gun sight-like prongs directed travelers toward the critical Continental Divide crossing at South Pass. Much closer was the dramatic Devil’s Gate, where the Sweetwater implausibly squeezes through a 30-foot wide abyss. While geologists have their own explanation, Shoshone and Arapahoe Indians believed that Devil’s Gate was created by an evil beast that prevented them from hunting and camping in the area. When warriors were finally able to impale the creature with a flurry of arrows, the enraged monster tore a mighty cleft in the rocks with his tusks and escaped.

As I sat daydreaming atop the whale-shaped dome, images from the great frontier artist William Henry Jackson flashed through my mind. Jackson had worked part of the Oregon Trail as a bullwhacker in 1866 and later passed Independence Rock as part of the Hayden Geological Survey. Because the panorama had changed so little since Jackson sketched, painted and photographed it, I felt like I had stepped into his work as a 21st-century extra. I visualized glittering stars hung over dozens of smoky campfires, illuminating white-canvassed Conestoga wagons circled next to the Sweetwater. Voices floated up from the past — with tones of hope and heartbreak — mixed with the moans of anxious livestock and barking dogs. Pondering the actual and imagined scenes, I recalled a line from William Faulkner’s Requiem for a Nun: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

As I was discovering, there’s something about the Sweetwater’s expansive landscape that’s long attracted intrepid vagabonds. Generations of Native Americans, pioneers, miners, trappers, traders, hermits, hippies, hunters and fly-fishing nomads have been doing this for ages. In an era when we seek authorities to guide us through every tidbit of life’s minutia, I like the idea of studying the topography, taking measured risks and then — like those early pioneers — cutting the cords and taking flight, like an untethered balloon released to the Wyoming wind.

Sweetwater, the Ultimate Sleeper

Shortly after hiking down Independence Rock, I was ambling up a Sweetwater canyon, working perfect iterations of riffles, runs and pools. Upstream, the river did a dramatic U-turn below a sheer escarpment. No one was around for miles.

I bounced a hopper pattern off the bank; a white maw immediately engulfed it. The trout streaked toward an undercut bank. If the miscreant disappeared into its root-encrusted lair — like one of his brothers just had — the chances of extracting it were slight. Pressure from my severely bowed rod barely kept the fish in play and, after several more blistering runs, a gleaming, golden-bellied 18-inch brown surrendered. And so it went as I wandered upstream — more pugilistic browns, mixed with rainbow missiles.

The Snake, Yellowstone, North Platte and Wind/Bighorn rank among Wyoming’s queen rivers, attracting fly anglers from around the globe. Beneath their glittering tiaras, however, lies a galaxy of worthy, lesser-known trout water. The Sweetwater River — a classic sleeper — falls into this category, like a whip-smart, overachieving kid no one seems to notice until she gradually blossoms into a cutting-edge artist or scientist. In The Wyoming Angling Guide, Chuck Fothergill and Bob Sterling aptly summed it up:

The Sweetwater, from its headwaters to Sweetwater Station, offers excellent fishing for browns and rainbows in a pristine environment. Difficult access causes it to be underrated as a fishery, but anglers seeking a primitive, wilderness experience will put it at the top of their list.

The Sweetwater sounds like it was named by a fly angler who discovered trout nirvana, but that’s not the case. One story is that a mule team spilled a load of sugar in the river. An alternative is that it was christened in 1823 by General William Ashley. Its relative purity and sweet taste compared favorably to the bitter, highly alkaline water from the nearby Red Desert and the more turbid North Platte downstream. Even though pioneers had the chore of crossing the winding, 238-mile long Sweetwater nine times, they greatly appreciated the reliable drinking water and riparian grazing areas for their stock.

A biogeographical curiosity of the Sweetwater and entire North Platte watershed is that pioneers reported no native trout. To the south, Colorado’s South Platte harbored indigenous greenback cutthroats; northward, the Wind/Big Horn basin sheltered Yellowstone cutthroats; and over the Continental Divide, the Colorado River drainage held its namesake cutts. Inherent coldwater habitat notwithstanding, the Sweetwater and other North Platte tributaries — like the Encampment, Laramie and Medicine Bow rivers — apparently lacked sufficient connectivity with surrounding trout water following the last Ice Age to naturally stock them.

According to local legend, the North Platte basin’s void was filled in the early 1870s, when a Union Pacific train transporting trout across Wyoming was delayed and the fish began dying. The crew reputedly backed the train over a North Platte bridge and dumped the surviving rainbows and brookies. However they arrived, the river swarmed with trout by the 1890s, when thrilled anglers reported landing 10-pound rainbows and 5-pound brookies. Brown trout were also successfully stocked, and they too grew prodigiously. All three species eventually took hold in the Sweetwater and other North Platte nooks and crannies, where they continue to flourish.

Unlike the larger North Platte, the Sweetwater is mainly approached by walking. At high water, paddlers attempt some reaches, but these expeditions require a good knowledge of the river. During normal flows, the Sweetwater is a pleasant stream to wade — approximately 20 to 30 feet across — large enough for good holding areas, yet small enough to readily read and cover the water.

One choice facing anglers — aside from which jeep track or animal trail will get you near the river — is whether to fish the faster mountain and canyon reaches, or slower desert stretches. The former present a diversity of water types, suitable for various surface and subsurface approaches, including pocket water nymphing. Alternatively, the latter holds long, deep pools separated by short riffles. During low-light conditions when hungry bruisers prowl for minnows, this more lethargic water is perfect for stripping streamers, leech patterns, and dragon and damsel fly nymphs along the banks.

Buoyant, boat-like attractors are Sweetwater trout treats on swifter reaches. Stimulators, Turck’s Tarantulas, Humpys, Wullfs, Trudes and PMXs are all solid menu choices. Parades of common Western hatches also spark surface action on the Sweetwater: mayflies (Blue-Wing Olives, Pale Morning Duns and Drakes), levitating Trico clouds (Golden and Little Yellow Stoneflies) caddis and midges.

The delicate challenge of presenting a minute Griffith’s Gnat or Trico Spinner notwithstanding, I maintain an abiding affection for the large, leggy stuff — the crawling, hopping, twitching terrestrials which infest the Sweetwater’s grassy banks from late summer to early fall. While bumbling, ravenous creatures like Mormon crickets are a godsend for fly anglers equipped with Chernobyl Ant-like monstrosities, their hordes periodically drove pioneers — desperate for green grazing pastures — to the brink of madness. An 1846 account from Oregon Trail trekker, Joel Palmer, described this creepy scene:

The ground for a strip of about four miles, was covered with black crickets of a large size. I saw some that were about three inches in length … our teams made great havoc among them; so numerous were they that we crushed them at every step.

In the Footprints of Manifest Destiny

eyond opportunities for lobbing bushy terrestrials, part of what’s compelling about the region’s streams is what divides and follows them. On the empty, 7,526-foot high Continental Divide separating the Sweetwater and Green River drainages, for example, lies one of the most historic geographic features in the West — South Pass. Long used by migrating wildlife and Native Americans, the pass was subsequently navigated by fur trader Robert Stuart in 1812. In the 1820s and 1830s, it became an important route for shipping supplies west to trappers and shipping fortunes in beaver pelts back East.

Pinched between the impassible Wind River Range and the punishing Red Desert, South Pass offered the most gradual incline over the northern Rocky Mountains. As explained by David Lageson and Darwin Spearing in Roadside Geology of Wyoming, “the basins of Wyoming provided a natural avenue across the Rockies,” while South Pass was the ‘hump’ of the Oregon Trail, the open door to the West — here the Continental Divide is easily crossed. … This was the critical moment in American history — knowledge of this pass opened up the West and the flood of emigration began.

Between 1840 and the 1869 completion of the first transcontinental railroad, approximately 500,000 emigrants struggled up the Sweetwater and over South Pass, seismically shifting the shape and character of the country. The pioneers were headed mainly for Oregon, California and Utah, drawn to adventure, fresh lives, free land, religious freedom and El Dorado gold fever.

For 19 months beginning in 1860, mail moved swiftly along the Sweetwater between St. Joseph, Mo., and San Francisco via galloping Pony Express riders. In March 1861, riders carried President Abraham Lincoln’s inaugural address up the Sweetwater to California in record time — more than 1,800 miles in seven days and 17 hours. But such heroic mail relays quickly became outdated once the first cross-continental telegraph was finished seven months later, using the same route along the Sweetwater.

Improved communication and the joy of reaching Independence Rock notwithstanding, the trail was a tough, sometimes heartbreaking trip, with thousands of wayfarers succumbing to cholera, accidents and weather. According to the Oregon-California Trails Association, nearly a tenth of the travelers perished: “The Oregon Trail is this nation’s longest graveyard … If evenly spaced along the length … there would be a grave every 50 yards from Missouri to Oregon City.”

As a growing tide of humanity swept westward — most surviving to new lives or even being born on the trail — gold was discovered around Sweetwater tributaries near South Pass in 1842, triggering a major rush in 1867. Thousands of eager adventurers flocked to mining camps at South Pass City, Atlantic City and Miner’s Delight, temporary home to the tempestuous Calamity Jane. South Pass City swelled to 3,000 people to briefly become the largest city in Wyoming Territory. By the 1870s, most of the lively bars and brothels closed as the boom ended, though periodic revivals followed. Today, South Pass City has been partially restored as one of Wyoming’s most compelling historical sites, Atlantic City maintains a faint pulse, while Miner’s Delight is deathly silent.

After a day of fishing and exploring South Pass, I rambled down the road to the 1893 Atlantic City Mercantile, a quirky saloon and estimable steakhouse with tin ceilings, an ancient bar and cornucopia of historical memorabilia. A retired Navy SEAL regaled visitors with tales about his mountain bike trip from Canada to Mexico, while a local played furious ragtime on the bar’s piano. Meanwhile, a menagerie of vintage deer and elk mounts impassively observed the proceedings from the walls; the stories they could tell … like why there’s a bullet hole in the back bar mirror.

Contemplating Life and the Cosmos from the Oregon Trail

ollowing the “Merc” steak feast, I gazed at an ineffable density of stars illuminating the Sweetwater riffle murmuring past my camp, the same celestial glitter pioneers had hung their hopes on. After a pull of bourbon, I pondered those people, this Sweetwater trip and an earlier youthful excursion. When I finally stumbled across the college graduation finish line, unemployed, I celebrated and bought a good backpack, cheap around-the-world air ticket and the adventure of a lifetime.

On my own sojourn, I wandered unguided, sleeping on riverbanks, magical Aegean beaches and in buck-a-night, cockroach-infested Asian hovels. I didn’t know how long I’d be gone. It turned out to be 15 months.

I felt, then, like I was living those Bob Dylan lyrics that have always grabbed me hard and thrown me up against the wall: “When you got nothing, you got nothing to lose/ You’re invisible now, you got no secrets to conceal.” And of course, the chorus: “How does it feel/How does it feel/To be on your own/With no direction home/Like a complete unknown/Like a rolling stone?”

Looking back at my hegira — easy by 19th-century standards — I’m astonished I’m still alive, but don’t regret a day. “We are here to laugh at the odds and live our lives so well that Death will tremble to take us,” advised poet Charles Bukowski. As best I can, I still try to recapture ghost-like shimmers of that feeling on Wyoming’s back roads, a country mile from careless, “carefree” youth.

Along the Sweetwater you can slip away from contemporary nonsense: No relentless texting, intrusive cell phone chatter, bloviating political buffoons, or TV updates on the Kardashians. It’s just the fierce Winds rip-sawing into blue sky; curious pronghorn families amidst rollercoaster sagebrush hills; a dust tornado trailing a rancher’s truck way up the road; and beyond, a lonely chasm of trout water. I’m off the radar screen and into terra incognita, a walk on the Wyoming wild side.

Those wagon train parties winding up the Sweetwater often carried popular handbooks, benefited from word-of-mouth experience, and relied heavily on social cohesion and the kindness of strangers. But after a certain amount of researching, planning and assistance, they just had to pull the stakes and go — or they never would.

Likewise, when it comes to traveling or fly fishing, I have nothing against help, expertise or good guides. Of the latter, I’ve benefited handsomely from them in Mexico and Costa Rica. It pays to recognize one’s bounds — I had no more chance of catching a permit or tarpon on my own than teaching a chimp to double-haul. But here’s my modest Sweetwater trout tip: Go now. Fill the tank and check the tires; study maps, road mazes and weather reports. Stock up with microbrews and tempeh; grab your 5 weight and boxes of attractors and terrestrials; and then follow the sage advice of David James Duncan in My Story as Told by Water: GO FISHING YOURSELF! We are a nation plagued with self-anointed experts, pundits, middle-persons. Away with them! Dare to be the bumbling hero of your very own fishing story … Anyone who teaches that solo experience is not the best teacher is not the best teacher. Solo experience now and then teaches the hard way, but the hard way is the unforgettable way … go catch a beautiful fish all by yourself!

If You Go: Navigating the Sweetwater

The Sweetwater drainage is remote, rugged and labyrinthine. A high-clearance, four-wheel drive vehicle helps, as will enthusiasm for hiking through hot, dry, rattlesnake-infested landscapes. On some back roads, rain will maroon you until things dry out. Anglers should come equipped with water, adequate maps and supplies. Visiting with local Bureau of Land Management (BLM), Bridger-Teton National Forest or Wyoming Game and Fish Department (WGFD) staff in advance is prudent. While small, the Sweetwater is one of Wyoming’s longest rivers: Where to start, from top to bottom?

Headwaters:

In its upper reaches, the Sweetwater courses through the Bridger-Teton National Forest, accessible via unpaved roads and trails. The headwaters rush down from Sweetwater Gap through the Bridger Wilderness Area, traversed by a trail for hikers and equestrians, who will mainly find pan-sized brookies and rainbows.

Downstream from the national forest, the stream gathers trout tributaries like the Little and East Sweetwater. Between the forest boundary and State Highway 28, the Sweetwater etches its way through land mainly managed by the BLM, including a primitive campground. Further down, the Lander Cutoff Road (County 446) follows the river east to Highway 28; it hugs the canyon top, with unmaintained spurs dropping toward a beautiful reach holding larger fish than above.

Middle:

Below Highway 28, the Sweetwater exits its mountainous source, twining through willows, sage-covered desert and craggy gorges. Land ownership continues to be BLM and private, with scattered state pieces. Due to its secluded character, visitors are encouraged to order the BLM 1:100,000 maps titled South Pass, Lander and Rattlesnake Hills; the first two cover the best trout water.

Between Atlantic City and Sweetwater Station, the Hudson-Atlantic City and Three Forks-Atlantic City Roads (BLM 2302 and County 22) provide access to the north side of the Sweetwater, via rough roads and trails twisting into the valley. On the south side, the Oregon Buttes Road (County 445) near South Pass City affords access through a puzzle of jeep tracks.

For the adventurous, a highlight of this middle section is the BLM’s Sweetwater Canyon Wilderness Study Area (WSA). Explore this water by parking on the rim and hiking into the chasm. The reward: solitude and a chance to tag browns that might make your reel scream like an osprey. Another wonderful place to slip away is The Nature Conservancy’s (TNC) Sweetwater Preserve — a sprawling high desert riparian area rich with wildlife and rare plants — with units above and below the WSA. Accessed by an old ranch road west of Sweetwater Station, the lower reach has two rustic, streamside cabins available by reservation. Fishing is catch-and-release only. Visitors must obtain prior written permission from TNC’s Lander office, 307.332.2971.

Lower:

The lower Sweetwater loops for many miles below the TNC preserve before its rendezvous with Pathfinder Reservoir, gradually becoming more of a warm, silty desert stream around Jeffrey City. On this bottom stretch, the WDGF has negotiated a series of leased walk-in accesses with private landowners (locations are posted on the agency website). Languid water and lower trout numbers notwithstanding, this is still a scenic, historic area to investigate.

- Mixed with large ranches, there is an abundance of public land in the Sweetwater basin, offering plenty of remote camping opportunities. Photo by Jeff Erickson

- The author works a hopper pattern in Sweetwater canyon. Photo by Jeff Erickson

- Along the middle section, especially, anglers can tangle with decent-sized browns (pictured) and rainbows. Photo by Jeff Erickson

- Devil’s Gate is an iconic geological feature along the Oregon Trail; a glimpse into the narrow chasm was eagerly anticipated by pioneers. Photo by Jeff Erickson

- The Sweetwater presents a variety of faces for anglers: tumbling mountain stretches; lonely, boulder-strewn canyons; and serpentine desert reaches. Photo by Jeff Erickson

- The Sweetwater rises clear and cold, high in the sprawling Wind River Range. Photo by Jeff Erickson

- Independence Rock was a pre-social media information board for pioneers, who used it to communicate with friends and family following them. Photo by Jeff Erickson

- The Nature Conservancy (TNC) owns a prime piece of the Sweetwater, preserving some of the best high desert riparian habitat in Wyoming. The Lander TNC offers stays at a rustic cabin, 307.332.2971. Photo by Jeff Erickson

- A maze of primitive roads — some following pioneer trails — provide access to the isolated Sweetwater country. Photo by Jeff Erickson

- The heartbeat of an old mining town, the Atlantic City Mercantile offers juicy steaks, cold micro-brews and a old West ambiance. Photo by Jeff Erickson

No Comments