08 Feb First Fish

WHEN MY WIFE AND I CRESTED THE FINAL mound of trail approaching Gneiss Lake in Montana’s Tobacco Root Mountains, the beauty of the jagged granite walls briefly halted us. Below, concentric circles of slow-rising cutthroat trout pocked Gneiss’ surface, and the click-clack of bounding mountain goats punctuated the silence. “This,” I thought, “is the genuine experience of fishing the high country in Montana. It’s authentic, the real deal.”

Turns out, though, not so much.

Upper Twin Lake, in the Wisconsin Creek drainage of the Tobacco Roots, hosts stocked westslope cutthroat trout. Photo by Joshua Bergan

Upper Twin Lake, in the Wisconsin Creek drainage of the Tobacco Roots, hosts stocked westslope cutthroat trout. Photo by Joshua Bergan

By the time we fished Gneiss, I had done enough research for my book, The Flyfisher’s Guide to Southwest Montana’s Mountain Lakes, to know that much of what presented itself as untouched was anything but. Very few of the fish we had cast to (and some of the lakes themselves) had occurred there naturally. Over the summers and miles of trails it took to research and write the book, I had grown increasingly curious: How many of the Northern Rockies’ lake-dwelling alpine trout had gotten there on their own?

I reached out to a number of fisheries biologists, rummaged through myriad books and scholarly articles, and Googled until my fingers were numb looking for answers. Data was scarce, but I was able to cobble together enough to realize that much of the highland angler’s experience did, in fact, take place in an environment that had been altered.

Trout first colonized the Northern Rockies during the most recent Ice Age, which ended roughly 12,000 years ago. The ice sheets and glaciers created torrents of flowing water that allowed bull trout, cutthroat, and rainbow trout to migrate inland from the Pacific Ocean. During that time, the Northern Rockies were a stew of ice and lava. Once these fish had gotten roughly to where there are today (rainbows had only gotten as far as the Kootenai drainage), our current drainages and divides finalized, isolating these fish till they became the populations and strains we know today.

In the overview below, I’ve included what some might consider low-elevation (subalpine) and larger-than-average mountain lakes such as such as Mussigbrod Lake in Montana’s Anaconda Range (about 6,500 feet in elevation and 105 acres) and Idaho’s Stanley Lake (about 6,500 feet and 185 acres). These largish subalpine stillwaters more commonly held native trout because there was less distance and elevation gain for fish to navigate. And of course, I included in my research more traditional small, high-alpine cirque lakes, but virtually all of those lakes’ connective tributaries had barriers (waterfalls too steep for trout to climb).

CUTTHROAT TROUT

Cutthroat trout, like this Yellowstone cutt, are the primary species found in mountain lakes in the Northern Rockies. Photo by Joshua Bergan

Near the end of the last Ice Age, the various strains of cutthroat trout became geographically isolated. In Montana, there were the Yellowstone cutthroat trout, which are native to the Yellowstone River drainage; and the westslope cutthroat trout, native to Western Montana. In Wyoming, there were native Colorado River cutts, Yellowstone cutts, Bear River cutts and Snake River cutts. In Idaho, there were westslope, Snake River, and Yellowstone cutthroat.

In some cases, these fish were able to travel out of their creeks and take up residence in a lake. In Montana, Upper and Lower Twin lakes near Anaconda on Twin Lakes Creek are believed to have held native westslope cutts, as did Doctor and Big Salmon lakes in the Bob Marshall Wilderness. In Southwest Montana, westslopes were likely present in Elk Lake in the Gravelly Range, Twin Lakes in the Beaverhead Mountains (where they can grow quite large), Squaw Lake in the west Pioneers, and Brownes Lake in the east Pioneers. Sportsman Lake in northern Yellowstone National Park’s Gallatin Range also probably held native westslopes.

Author Finis Mitchell stated in his book, Wind River Trails, that only five of the Wind River Range (Wyoming) lakes that he encountered in the 1920s and ‘30s already had fish, which would have likely been native Colorado River cutthroat. One biologist I spoke with speculated that those five could have been Mud, Meeks, Big Sandy, V, and Johnson lakes in the Big Sandy drainage.

Idaho’s Bitterroot Range hosted a handful of lakes that held native cutts, including Lost Lakes number one, two, and three, Fish Lake in the Long Creek drainage, another Fish Lake in the Sponge Creek drainage, Moose Creek Lake number two, California Lake, Big Sand Lake, and Hidden Lakes number one and two. Elsewhere in Idaho, I was unable to find specific lakes with native cutthroat trout. But according to Idaho Fish and Game’s Sportfishing Program coordinator Martin Koenig: “Most of the large lakes in the Sawtooth Valley (Redfish, Alturas, Petit, Stanley, etc.) and other large natural high-elevation lakes like Payette, Henry’s, etc. had historically native trout (and salmon) populations.”

It’s speculated that in Yellowstone National Park, 17 of the 140 or so lakes held native fish — a higher percentage than elsewhere in the Northern Rockies. This likely is due to the fact that Yellowstone does not have the craggy, steep landscape that characterize most mountain ranges. Specifically, according to fish biologist Philip Doepke, Yellowstone, Alder, Chipmunk, McBride, Sportsman, Sylvan, Trout, Heart, Riddle, Turbid, Mariposa, and a few other lakes are all thought to have been home to Yellowstone cutthroat trout. Most of these lakes are directly connected to Yellowstone Lake.

Two of the only small, high-alpine lakes to host native trout were Heather Lake (9,370 feet, 4 acres) and Peace Lake (8,750 feet, 3 acres), both up Wounded Man Creek in the Slough Creek drainage of Montana’s Beartooth Mountains (both are unnamed on most maps). Each connected to the Yellowstone River without a fish barrier and contained Yellowstone cutthroat trout. These trout, however, are said to remain quite small.

Cutthroat trout are still present in most of these lakes.

ARTIC GRAYLING

Native populations of adfluvial Arctic grayling were only found in Montana’s Big Hole River drainage. Photo by Joshua Bergan

In the Northern Rockies, arctic grayling were native only to the upper Missouri River drainage, and populations of lake-dwelling arctic grayling were rarer than mountain lake cutthroat. There are thought to have been pre-stocking populations only in Mussigbrod and Pintler lakes in the Anaconda Range, and Lower Miner Lake in the Beaverheads.

LAKE TROUT

Lake trout, believe it or not, have maintained populations in Elk Lake in Montana’s Gravellies and Twin Lakes in the Beaverheads since the last Ice Age — the only two lakes west of the Great Lakes with this surprising honor. Why and how lakers ended up only in these two lakes is a bit of a mystery, but possibly it had something to do with the fact that these lakes had suitable spawning habitat (lake trout are main-stem spawners, meaning they do not run up creeks but rather spawn in shallow areas of lakes).

This is noteworthy because of the well-publicized illegal introduction of lake trout into Yellowstone Lake, where they are a scourge. Yellowstone Lake’s vast depth, ice-cold water, and spawning areas have proven to be ideal habitat for lake trout. And since cutthroat trout were able to find their way there, it makes one wonder why lakers did not since they were able to get to nearby Elk Lake. A small number of Jackson, Wyoming, eccentrics have put forth a conspiracy theory suggesting that lake trout might have been native to Yellowstone Lake, but that’s a topic for another article.

RAINBOW TROUT

Hidden Lake, Glacier National Park. Photo by Jeremie Hollman

Columbia River redband rainbow trout made it as far inland as Montana’s Kootenai River drainage and were native to much of Idaho. According to Jim Fredericks, chief of fisheries for the Idaho Department of Fish and Game, a number of mountain lakes in Western Idaho had native populations of rainbow trout, but I was unable to learn of any specific locations.

BULL TROUT

Upper and Lower Twin lakes on Twin Lakes Creek near Anaconda, Montana, are presumed to have held native bull trout; probably so did Doctor and Big Salmon lakes in the South Fork of the Flathead River watershed.

The two aforementioned Fish lakes in Idaho’s Bitterroot Mountains also are thought to have held native bull trout.

HISTORY OF MOUNTAIN-LAKE STOCKING

Since about the 1850s, trappers, loggers, miners, cattlemen, and other pioneer types planted fish in mountain lakes for both sport and sustenance. Such “bucket biology” is considered unethical today, as non-native species can seriously disrupt ecosystems.

The Montana Fish and Game Department (as it was known then) was created in 1901, and established the first fishing regulations booklet.

Around 1900, the government began formally stocking a few mountain lakes in the Northern Rockies. Also at about this time, the now-defunct U.S. Fish Commission started pouring fish into Yellowstone National Park. Both Idaho and Montana’s first state-run trout hatcheries were built in 1907, though the federal Fish and Wildlife Service hatchery in Bozeman was already stocking fisheries by then. Records weren’t well kept, but cutthroat, rainbow, and even a few golden trout likely were the main species being stocked, a pattern that continued for the next several decades.

In this early era of sanctioned stocking, little attention was given to the adverse impacts of planting non-natives, even by government agencies. For example, Idaho Fish & Game had tried stocking arctic char and Atlantic salmon in some lakes, and the U.S. Fish Commission experimented with putting largemouth bass into some Yellowstone National Park waters. In those days, fish stocking was generally done either by pack animals or hikers carrying fish in milk cans with cold water. By the 1950s, aircraft had become more available and dropping trout from above became the preferred method.

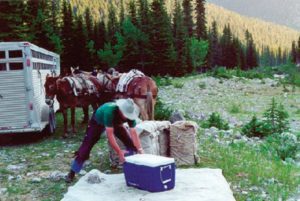

Finis Mitchell used a pack train to stock trout in the Wind River Mountains. Photo by University of Idaho Press/Wind River Trails

Finis Mitchell, the so-called Lord of the Winds, is credited with making the Wind River Range the fishy place it is today. He supposedly took it upon himself to plant more than 2.5 million trout in over 300 Wind River Range lakes in the 1920s and ‘30s — an explicit act of bucket biology. Interestingly, he still is hailed as a hero, and even was given an honorary doctorate by the University of Wyoming. Apparently, no major ecologic catastrophes resulted from his efforts.

Some lakes in Yellowstone, including Yellowstone and Trout lakes, were actually used as fish hatcheries, though Trout Lake was used for rainbow trout (which accounts for the rare but big rainbow trout there today). These were closed in the 1950s.

An early hatchery truck brought brood stock to a Montana lake. Photo by Montana fish, Wildlife and Parks

During the early 1970s (at about the time Montana stopped stocking rivers as a policy), fisheries managers favored planting cutthroat trout in mountain lakes because of their native status. But even then, Yellowstone cutts were stocked in westslope territory because of their fast growth rates — and they made for better sport. It wasn’t until the early 2000s that fisheries managers decided to stock strictly native strains of cutthroat due to hybridization concerns. This is the current prevailing paradigm among Northern Rockies fisheries managers. However, there are still a number of residual, self-sustaining populations of non-native cutthroat. (Wild Yellowstone cutts still thrive in some of Montana’s Madison Range lakes, for example.)

Grayling are still stocked in a few lakes (mostly grayling eggs nowadays), golden trout are planted in a small number of lakes where natural reproduction is unlikely (biologists like to use lakes where reproduction is possible for cutthroats), and native strains of cutts are stocked in the rest of the stocked mountain lakes.

Even today, pack horses are used to stock some high-altitude lakes. Photo by Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks

The only lakes that currently are stocked in Yellowstone are the Goose Lake chain, which is being planted with native westslope cutthroat trout as part of the park’s Native Fish Conservation Plan.

Today, mountain lake fish stocking is done by a variety of methods, including dropping fry and fingerlings from airplanes and helicopters (which seems to be the most common method), as well as via ATVs, motorcycles, mountain bikes, and hiking with coolers, and, even by pack horses with panniers.

Despite their pristine nature, mountain lakes are hardly untouched. But it doesn’t much matter when you’re hooked into a spotless, lavender-and-pineapple, black-spotted trout on the shore of a jade cirque lake. Both angler and trout are exactly where they’re supposed to be.

No Comments