05 Oct Local Knowledge: Jim Posewitz

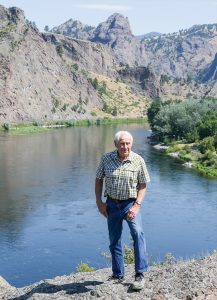

A tireless advocate for the conservation of natural resources, Jim Posewitz is considered by many to be the father of hunting ethics in America. He sits in his office, perched on a hill above downtown Helena, surrounded by memorabilia from a lifetime spent protecting wild places and pursuing wild animals in those places. Behind him, a European mount of an elk he shot in Paradise Valley hangs on the wall. Plaques and awards from conservation groups, honoring Posewitz’s commitment to the environment, adorn the room. A freestanding, glass-front bookcase is loaded with case studies from conservation projects and biographies of Theodore Roosevelt. A bobbleheaded doll of Teddy oversees Posewitz’s work through wire-rimmed glasses.

At 82 years old, Jim Posewitz has spent most of his

life fighting for ethical sportsmanship and the conservation

of resources.

Posewitz is 82 years old. As he talks, his blue-green eyes smile at you. His laugh is a loud bark that comes out of nowhere. His voice is as gravelly as a river bottom. Posewitz is prone to quoting Teddy Roosevelt and Teddy Blue Abbott and Granville Stuart. “You ain’t trying hard enough if they don’t shoot you out of the saddle,” he says, summing up his self-admitted feather-ruffling approach to fighting for what he believes in.

Posewitz was not a born outdoorsman. “Growing up in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, in the 1940s and 50s, my whole world revolved around athletics,” he says. His father, who once played professional basketball for the Sheboygan Redskins, owned a gas station and chartered buses to take locals to every Green Bay Packers’ home game. “All through high school, that was my orientation. Athletics.”

Hunting and fishing weren’t draws for Posewitz as a young man because the opportunity wasn’t there. “Rural Wisconsin was a place depleted of wildlife. There wasn’t a deer in the county where I grew up since who knows when.” Posewitz recalls an example from his days with the Boy Scouts. “One of the counsellors would mark a trail in the woods with a deer foot he had, so the Boy Scouts could track the false trail. Then another counsellor would hide in the trees with a mounted deer head and the scouts would spotlight him.”

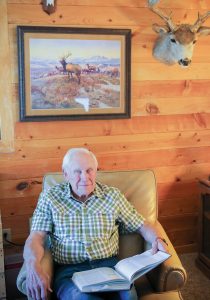

Posewitz sits in his office, under a print of

Charles M. Russell’s “The Exalted Ruler.”

Amongst the awards and certificates displayed in Posewitz’s office, there are also greeting cards, one of which demands, “You Better Get Well.” As he recounts his journey from Wisconsin to Montana, Posewitz breaks off to field phone calls from friends and colleagues who inquire about his health. “They are going to take some more around the edges,” he explains rather matter-of-factly. “Just the tumors.” Posewitz has been diagnosed with an aggressive form of bladder cancer, and he is headed to the operating room the following day for more surgery.

He hangs up the phone and smiles, then tells the story of how he came to Montana from the Midwest. “My high school football team was playing East Green Bay. The announcer said, ‘The tackle again by Posewitz,’ over the PA system. My fantasy is that they heard that announcement all the way in Montana.” Montana State College — now Montana State University (MSU) — recruited Posewitz to play tight end and outside linebacker. “I had no idea where Montana was when I was recruited,” he says. “I had to get out a map.”

Posewitz began working for the Montana Fish and Game Commission (the agency that became today’s Fish, Wildlife & Parks, or FWP) in 1955, while he was still in college. After earning his bachelor’s degree, he spent two years in the Army as an operations/intelligence assistant. In 1961, after getting his master’s degree in fish and wildlife management from MSU, Posewitz started working full time for Fish and Game, beginning a career that would last more than 30 years.

Posewitz, at the far left, was included in a 1978 Life magazine feature on efforts to save the integrity of the Yellowstone River.

Posewitz, at the far left, was included in a 1978 Life magazine feature on efforts to save the integrity of the Yellowstone River.

In the mid-1960s, as regional fish manager and head of the Water Resource Development Unit of FWP, Posewitz fought the construction of additional dams on the Missouri River above Fort Peck Reservoir. Then in the 1970s, Posewitz took the lead on protecting the Yellowstone River when both the federal government and energy corporations proposed the construction of 42 coal-fired power plants. About 2.6 million acre-feet of the Yellowstone River’s flow would have been diverted to power steam turbines and cool the coal gasification plants. For a river with a flow that ranges from 4 to 9 million acre-feet, depending on the time of year, such a depletion would have been devastating. In the end, only two additional power plants were constructed, bringing the total to four. Once the Yellowstone was protected, Posewitz moved his attention to the Rocky Mountain Front, where proposed drilling threatened wildlife resources.

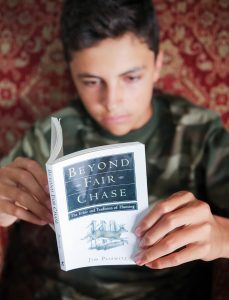

Cole Nashan, a 16-year-old hunter,

reads Posewitz’s book which he

received in a hunter’s education

course in Livingston, Montana.

Posewitz often found himself stuck in a political no-man’s land, trying to defend Montana’s fish and wildlife and the wild places they call home, even in the face of pressure from his bosses at FWP, the governor’s office, and Montana’s representatives in Washington, D.C. He remembers fighting to protect the Boulder River between Butte and Helena, after senators Mike Mansfield and Lee Metcalf had promised that interstates 15 and 90 would intersect in Butte. Posewitz stood his ground, determined to not let the Boulder get straightened to accommodate I-15. “The governor said, ‘Give Fish and Game everything they want to make it happen.’ So we designed extra bridges to keep the Boulder River from getting mauled.” Posewitz sums up his attitude by explaining, “I would be very uncomfortable in later retirement if I had made political presumptions about what I couldn’t do. You don’t know if you’re pushing hard enough until you break something.”

Posewitz retired from FWP in 1993, and began to devote more time to hunter education and ethics, founding Orion — The Hunters’ Institute, and penning the classic text Beyond Fair Chase, which was published in 1994. “I went through two degrees in fish and wildlife science, and I could tell you how many fawns a doe would have or how many roe a fish would produce, but I hadn’t studied anything about ethics,” he says. More than 700,000 copies of the book are in print and Beyond Fair Chase has become a mainstay of hunter education programs across the country.

Beyond Fair Chase is a small book, not much larger than a deck of playing cards, yet the message contained within its text is powerful. Part of the book’s appeal comes from how Posewitz illustrates high-minded concepts of conservation and ethics with real-life stories of hunters facing ethical tests. In one passage, “The Story of a Lost Bull,” Posewitz recounts the tale of a bow hunter who spent 30 days searching for a bull elk he had wounded, before finally finding and tagging the remains. “It happened outside Helena,” Posewitz says. “I sent the guy the story, sent him a pre-publication copy of the book, and never heard back from him. I sent him a copy of the book when it came out, never heard from him. Then, many years later, I was helping my wife run a hunters’ check station. A guy comes up to me, sticks his hand out, and says, ‘I’m your hunter.’ I asked him why he never responded when I sent him the book for his thoughts and he said, ‘You had it right.’”

More recently, Posewitz found himself in the back of an ambulance, headed from Helena to Butte due to complications from surgery. While talking with the EMT about Beyond Fair Chase, which she’d read six years earlier while taking a hunter’s education course, the ambulance slowed to navigate a series of sharp turns in the highway. Posewitz felt the swaying of the ambulance deep in his gut, remembering a time when he stood his ground to protect wild things and wild places that had no voice of their own. “I know right where we are,” Posewitz told the EMT. “I put these contortions in the road.”

When asked to identify the most common misconception about hunters, Posewitz answers, “The biggest void, in and out of the hunting community, is appreciation for exactly what has been accomplished in that, in a democracy, wildlife is for anyone and everyone. We restored a resource that was at the brink of depletion.” Those blue-green eyes shine with the thought of it. “Today we have deer in our cities, bears in our orchards, and goose shit on every golf shoe in Montana. We don’t teach that.”

No Comments