07 Jun Bears in Yellowstone

WHEN PRESIDENT WARREN G. HARDING FED A BEAR named Max in Yellowstone National Park in 1923, he made sure to do it the right way. He didn’t tease Max or offer food directly from his hand. Instead he held out a bowl of molasses that Max, sitting on a tree branch about 7 feet off the ground, could lean over and lick. Harding, in a dapper suit, tie, and hat, later enticed the bear onto the ground — rangers had treed it for his convenience — where he fed it from another bowl. Yellowstone Superintendent Horace Albright looked on with approval.

Today, we would be appalled. Feeding bears debases the quality we most admire in them: wildness. But our societal journey to this value system required that intermediate step. For bears to evolve beyond rampaging Satans, we first needed to see them as performers, mugging for treats as if asking to be included in our society. Only then could we come to see them as creatures of their own worthy society, beings whose natural setting is their defining characteristic.

In the 1930s, tourists sat in bleachers to watch grizzlies eating garbage on a stage.

In the 1930s, tourists sat in bleachers to watch grizzlies eating garbage on a stage.

The earliest Anglos in the Yellowstone area generally killed as many bears as possible. The first step we took to change that relationship: We kept them alive, but insisted that they perform for our emotional gratification.

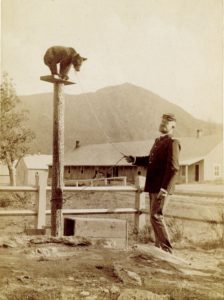

In 1890, Yellowstone Superintendent George Anderson kept a bear chained outside his home at Mammoth Hot Springs. When it was fed by his maid, or climbed a 10-foot pole to stand on a platform, it demonstrated the potential for all of its species to obey man’s dominion.

In 1923, President Warren Harding fed a bowl of molasses to a bear named Max. Photo courtesy Library of Congress

By 1897, when naturalist Ernest Thompson Seton delightedly buried himself in the “cabbage-stalks, old potato-peelings, tomato-cans, and carrion” dumped behind the Fountain Hotel in order to observe and sketch bears, he was demonstrating the potential for a shift. Although the bears Seton watched were eating human garbage, their behavior was somewhat more authentic than the antics of those chained in a backyard.

These bears were, as Seton phrased it, “half tame.” They acted gently if mysteriously, allowing people to believe they were grateful to receive our garbage. From the 1890s through the 1940s, people believed that feeding a bear removed from it the barbarity that had made it so fearsome. To half-tame a bear was to give it an enlightened place in the human world that might otherwise feel compelled to destroy it.

In the 1890s, Yellowstone Superintendent George Anderson kept a black bear chained in his yard at Mammoth Hot Springs. Courtesy National Park Service, Yellowstone National Park, Yell 1657

Yellowstone became the unique, magnificent home of that taming process. We came to see the park as a sanctuary that helped prevent these animals’ extinction. Our reward for setting aside this land was to witness its bears performing for us.

In imagining that bears could be something other than bloodthirsty monsters, Anderson and Seton were relatively bold and compassionate. They gave bears a chance to adapt to their conquerors, rather than serving as victims or trophies of the conquest.

In the 1920s, Yellowstone ran a zoo at Mammoth where tourists could meet Gyp, a bear likely named after Doctor Dolittle’s dog. According to Alice Wondrak Biel’s informative book Do (Not) Feed the Bears, Gyp helped visitors feel at home in a potentially intimidating wilderness. Gyp bridged the gap between wild and tame — just as the park itself did, and continues to do, on a broader scale.

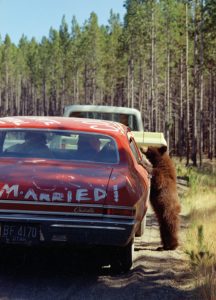

One of Yellowstone’s biggest 1920s celebrities was a bear named Jesse James, who would step into the path of oncoming cars and rear up on his hind legs to stage “a hold-up” for treats. Compared to Gyp, Jesse James’ life was natural and free. He was performing for people, but this act was only semi-scripted — like a reality TV show. He was never confined. He could travel where he wanted and eat what he chose. People were delighted when he chose to eat candy, a validation of their own desires.

In the 1930s, bear feeding shows became formalized. At Otter Creek, near Canyon Village, hotel garbage was dumped on an 18-by-40-foot feeding platform at specific times of day. Up to 250 spectators could sit on hillside bleachers to watch as many as 70 noshing bears. These shows (and smaller ones near Old Faithful and Lake Hotel) were often standing-room-only affairs — one report counted more than 600 cars in Otter Creek’s dedicated parking lot.

A growing concern that feeding bears was not “natural” led to a backlash against the performances. The ensuing battle can be seen as pitting wildlife advocates against administrators, or science against sentimentalism. But more broadly, it can also be seen as a realization that Seton’s “half tame” idea had done its job and needed to be set aside. Now that people saw bears up close, appreciated them, rooted for them, and no longer felt obliged to destroy them, they no longer needed a taming ritual. The magic of a bear, people came to believe, lay not in being tamed but in being wild.

By the 1960s, the problems with garbage-attenuated bears were becoming clear. Photo courtesy Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming, U.S.A.; Jack Richard Collection, PN.89.24.3960.32

By the 1960s, the problems with garbage-attenuated bears were becoming clear. Photo courtesy Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming, U.S.A.; Jack Richard Collection, PN.89.24.3960.32

That change in belief changed the lives of Yellowstone bears. During World War II, the park took advantage of low visitation to close its bear feeding shows (not the dumps, just the shows; not the bears’ food, just their performance value). The park changed its message about bears, from “hand-feeding bears can be dangerous” to “bears are dangerous.” It gradually started enforcing its ban on feeding bears from cars.

Of course the new message had to fight lingering anthropomorphism. Cuddly bears dominated popular culture: Winnie-the-Pooh, Teddy, Smokey, and by 1958 a “Jellystone” inhabitant named Yogi. Meanwhile, veteran bear-feeding tourists wanted to share the exotic intimacy of that experience with their children. But especially as accumulating scientific evidence demonstrated the perils to bear populations of continued collisions with human society, society gradually evolved.

Seeing bears from your car in Yellowstone became a cultural rite, passed down through generations. Photo courtesy Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming, U.S.A.; Jack Richard Collection, PN.89.116.21435.22

Today, people generally want bears to be wild. They get upset at the tiny-brained creatures known as “stupid tourists” who approach too close, and angry with managers who execute bears that have felt compelled to attack “stupid tourists.”

We see bears as noble icons of wilderness — a paradigm that has its own pitfalls. Because population growth and development reduce wildness, bears can become unwitting weapons in battles that are really about growth. Furthermore, by elevating bear “wildness” over bear survival, we potentially limit options that scientists once recommended to help grizzlies avoid extinction.

Yogi Bear glamorized the interactions of bears and people in “Jellystone.” In 1961, Yellowstone tried, not very successfully, to co-opt Yogi for a “Don’t feed the bears” message. Courtesy National Park Service, Yellowstone National Park, Yell 40281

For example, in the late 1960s, bear researchers Frank and John Craighead urged Yellowstone to wean grizzlies off hotel garbage by piling elk carcasses in remote areas. Administrators rejected that practice as artificial and thus contrary to wilderness values. Instead, they insisted, wild bears must quit garbage cold turkey. As the Craigheads predicted, area grizzlies suffered, nearly to extinction.

Today, despite healthy grizzly populations, some bear advocates are concerned about their long-term survival. Whitebark pine nuts, an important food source, may be especially threatened by climate change. If grizzly populations do drop, would carcass piles now be an acceptable measure?

Beyond the science is a question about societal values. The history of bears in Yellowstone is the history of what bears mean to us. If grizzly populations decline, and we see that as an indicator of a deeper crisis in climate or wilderness, maybe we should focus on addressing the crisis rather than using artificial means to prop up the indicator. But it’s confusing: Given what global warming tells us about humans’ planetary impacts, how do we define artificial? Or, for that matter, wild?

Thinking about the changing ideas about bears can help explain the past, though not necessarily help us navigate the future. The problem is that changes in people’s values are even harder to predict than whitebark pine nut yields. But in this unpredictability also lies hope. We know that positive changes in values and behaviors are possible. After all, if they hadn’t changed in the past, neither we nor Yellowstone’s bears would be where we are today.

No Comments