29 Jul Artist of the West: Close Encounters

Nearly face-to-face with an anvil-headed Alaskan wolverine, Greg Beecham realized he might be on the dinner menu. The artist had just watched the creature sprint across the mossy muskeg toward him for a quarter mile without stopping, while clenching an entire caribou leg in its fierce jaws.

The standoff came just after Beecham flagged the creature down by yelling at it, as it walked past him along a remote road near Prudhoe Bay in northern Alaska. He was visiting the area with a friend who worked in the oilfields there.

“He just started walking up the road and I thought, ‘I don’t want him to leave, I want to get some more pictures!’” Beecham recalls. With a self-effacing expression, he points at his head as if he knows that was a crazy thing to do. His yell turned the creature around, still clutching the cruddy caribou leg. It had previously taken no notice of Beecham despite having passed within 30 feet. The beast dropped the leg to amble toward him.

“There’s no fear,” Beecham says. “There’s just ‘What are you?’”

Soon, it was 10 feet away, coming in low. Its stance and body language worried the man who knows his wildlife. As much danger as he was in, Beecham still took a moment to marvel at the animal’s obvious power.

“It was the most incredible experience, but all of a sudden I started thinking, ‘What am I doing?’” He had nothing for protection. No bear spray, no knife. “I gotta do something to stop him before he’s a foot from me and he decides I’m worth biting. So I got down low like this and I just ‘Grrrrr!’ growled at him because I didn’t know what else to do; because running from a predator’s just not what you do.”

The wolverine exhibited no fear, instead it sized Beecham up, then apparently decided he wasn’t worth the time and effort.

“I’m being anthropomorphic here, but it’s almost like that’s what he felt, because he just sort of sauntered back to his leg, kinda looked at me again like, ‘I don’t know what you are and I don’t care,’ and he walked off with his leg.”

This time, Beecham did nothing to regain the wolverine’s attention.

Such close encounters come packaged with Beecham’s passion for his subject matter. He has no shortage of stories where he’s close, maybe too close, to the wildlife he loves to paint. An afternoon with him is filled with scads of them — each as interesting as the last.

“Well, I go overboard,” he admits. Among the examples: He’s been bluff charged by elephants and moose, and has chased galloping wild horses through a sagebrush steppe in a new sport utility vehicle (which took a beating in the process). But he recognizes limits. Once he backed down when another artist wanted to push the limits in Yellowstone with a grizzly bear. That effort may have saved his life since a grizzly killed a man and mauled a woman in the same spot not long afterward.

Beecham prefers to watch wildlife with other artists, because they understand that it’s necessary to witness the life, the gestures and the personality of animals in order to convey them realistically in art.

This mentality is vital to Beecham, who is quick to quote legendary author Leo Tolstoy on the matter of what constitutes art. Tolstoy wrote in a critique of another writer’s work, that creating art requires three ingredients. First, the artist must have good technical skills. Second, he must say something new. Finally, the artist needs to have a moral relationship with the subject matter.

In Beecham’s case, his moral authority and ability to address the novel comes from hours spent observing wildlife, learning how animals move and act. “With critters, every time you go out they tell you new stuff,” he says.

During the 37 years he’s spent as a professional artist, Beecham has developed a solid technique to realistically capture the gestures and forms of his subjects. That completes Tolstoy’s trifecta, and the result is art that elicits an emotional response from people.

Beecham has been a part of the Invitational Art Exhibition at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City for the past decade, and he says it helped catapult him to instant success after 25 years in the business. Since joining the show, he’s won three of the last seven Pittman Wildlife Awards along with the Buyers’ Choice Award.

Mick Savage is a member of the Prix de West board, Beecham’s fan and friend, and has a lot of insight into his work. He has taken a painting workshop from Beecham and as a “modest collector” of his work, says he’s always looking for another Beecham to add to his collection.

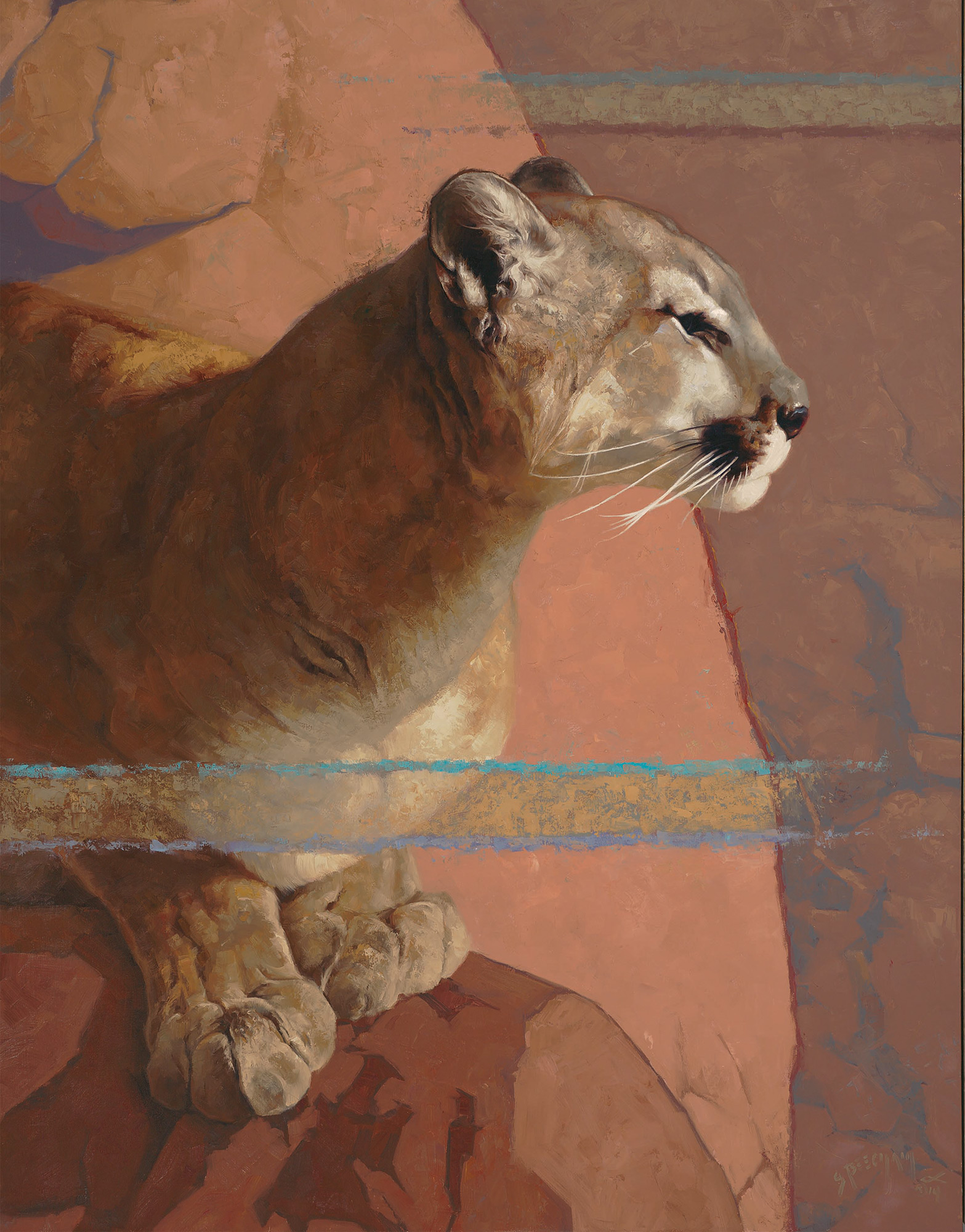

Beecham knows how to portray an animal, according to Savage. Its gestures, moods and even personality flow through the brush onto the canvas, and often, enhanced light helps tell the story more powerfully. Increasingly, Savage says, Beecham is shifting his style, especially as it pertains to each painting’s architecture and design.

“As his art evolves we see an increased sense of abstraction in his paintings,” he says. To illustrate his point, Savage points to a bobcat painting that Beecham sent to this year’s Prix de West show. The crouched bobcat’s face takes up a prominent spot in the upper golden third of the painting as it pauses alertly while clambering down a boulder. The bottom of the painting is composed of nothing more than the rock face. Savage says the lower portion of the painting could almost stand alone as an abstract painting with a meaningful collection of shapes.

“He’s bringing out the abstract quality more explicitly in some paintings,” Savage says. “I’d be surprised if we don’t see more of that in the future.”

As for the present, Greg Fulton (Beecham’s lone gallery representative) says things are chugging along well for the artist, though Beecham himself tends to think his popularity has hit a plateau. Fulton is the managing partner of Astoria Fine Art in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. When Fulton broke off from his former employer to start his own gallery, Beecham was at the nucleus of that effort. Other artists soon joined, but Fulton says since the gallery’s inception, Beecham has outsold every other painter each year. Beecham even gets his own show annually during the renowned Jackson Hole Fall Arts Festival.

“I rely heavily on that show and he’s always come through for me,” Fulton says, adding that Beecham is the hardest-working artist Fulton has ever represented. But Fulton also acknowledges a shift in Beecham’s work toward abstractions and new concepts.

“He’s less of a Realist today than he was five years ago,” Fulton says. “I think he’s doing now what he wants to be doing.”

Still, anyone concerned about Beecham’s shift doesn’t have too much to fear.

“His production is still 90 percent good old Greg Beecham,” Fulton says. “He’s not going anywhere. … Nobody has to worry about the more classical Greg Beecham disappearing.”

Unless, of course, he’s disappearing into the wilderness for more close encounters.

- Artist Greg Beecham in the field. Photo by Mark Quigley

- “The Aspen Leaf” | Oil on Linen | 24” x 18”

- “The Old Log” | Oil on Linen | 30” x 30”

- “Dawn Patrol” | Oil on Linen | 18” x 24”

- “The Northfork and Big Nasty” | Oil on Linen | 48” x 60”

- “Lionheart” | Oil on Linen | 40” x 30”

- “The Buddy System” | Oil on Linen | 24” x 48”

No Comments