20 Aug Fish Tales: Where the Wild Things Are

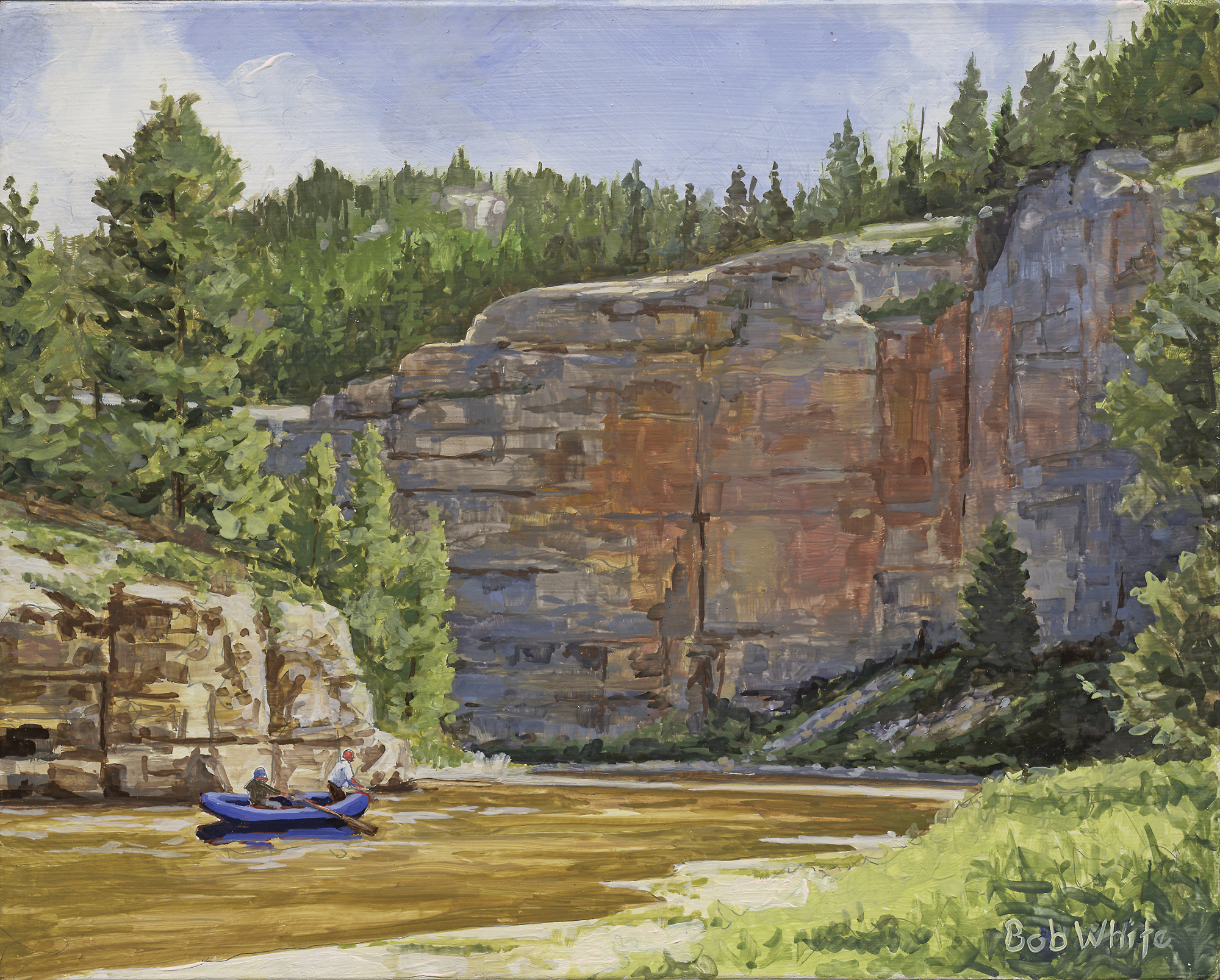

IN THE LATE AFTERNOON, at the spot where Rock Creek empties into the Smith River, I finally was released from the privileged prison of the blue rubber raft in which I had been riding. Ever since we’d put in that morning near White Sulphur Springs, I had been fishing among people who rode inflatable boats that were identical to mine. It was August and the Smith was low and slow, quickened only by the occasional steep riffle, and as we oared through the day at a leisurely pace, we cast grasshopper patterns against the canyon walls in search of troll-like brown trout that lurked in waterline caves. Frequently, one blue craft in our pneumatic convoy would overtake another, the flashing fly lines would settle to the water for a few minutes and there would be banter and laughter.

My companions were all wonderful people — good company, and everyone excited to be setting out on a five-day float trip between the ancient and soaring limestone cliffs that make the Smith one of West’s most enchanting rivers.

But I am at heart a small-stream fly fisherman, and a small-stream fly fisherman is by nature a feral, secretive, sometimes antisocial, creature. On larger rivers we may tolerate, even enjoy, the presence of others. But put one of us on a twisting, siren-singing enigma of a brook or a creek and an almost physiological change overtakes us. Crouching and furtive, with every nerve and muscle radiating a predatory seriousness and sense of purpose, we are compelled to navigate our way upstream on an urgent and solitary quest for something that even we would be hard pressed to define.

Best just to keep your distance.

Rock Creek is a limestone-walled version of the Smith itself, but smaller — and therefore, of course, sweeter. Brian, my guide, said, “It’s okay if you want to fish this for a while. But be back by suppertime. That’s two hours from now.”

But I barely heard him. I scrambled from the raft, sniffed the air once or twice, and lit out.

And then I was alone. No one to make suggestions, ask questions, be solicitous or fuss over me if I got jabbed by a snake. This was Eden.

I followed the creek through sunlit canyon meadows filled with yellow coneflowers and clattering grasshoppers and found myself presented with a chain of perfect pools, each one demanding the exacting small-stream tactics of a short, accurate line and knee-crawling stealth. I would spot several trout finning in the window-clear 2- to 3-foot depths of an upstream pool, and I would immediately drop low and work my way around the bankside willows until I was kneeling in the grass at the point where the creek just began to widen. I’d dap in a grasshopper imitation and let the current sweep it toward me along the edge of the bank. Invariably, before the others got wise to me, one or two vividly colored brown trout of up to 13 inches would lazily surface to eat that hopper.

Two hours passed, and then three, and yet the setting sun kept drawing me farther from the Smith and my group’s campsite across the river from the mouth of the creek.

At last, a 15-foot cast into a frothy plunge pool the size of a kitchen sink produced a splashing strike and a trout of around 16 inches that wore some of the blackest spots I’d ever seen on a brown. I knew I was unlikely to catch a bigger trout in this little creek, and it was this knowledge that finally broke the spell and allowed me to head back downstream toward the Smith.

And yet as the evening shadows followed me out of the magical side canyon, I could not keep myself from stopping to run a beadhead nymph through some of the larger pools that I’d hoppered on the way up.

It was twilight by the time I reached camp, and I was relieved to find that my truancy, if not forgiven, was silently overlooked. Someone gave me a plate of hot food, and I sat down to join the campfire conversation. My companions all were happy; the fishing and floating had been fine, and tomorrow promised more of the same. When I was called upon for an account of my day’s fishing, it was the Smith I spoke about, and when someone pressed me about my solo undertaking, I kept my comments vague. The creek was mine; no one else could have a piece.

Throughout the evening, as I talked and listened and laughed, I found myself looking across the river toward the perfect little canyon of Rock Creek. I kept turning my eyes there even after it had grown so dark that there was nothing left to see.

No Comments