24 Jul Images of the West: The Silence of Art

SO MUCH HAS BEEN WRITTEN about fly fishing and about poetry — and so little of it written well — that writing about poetry and fly-fishing should count as an easy task, yet neither the art of fly-fishing nor the art of poetry require much discussion. Both are best practiced in silence.

We all know this, yet few of us practice the art of silence well, either.

Of course, a few people have said reasonable things about all three of these arts, which, after all, are no more separable from each other than light from sun or the tides from the moon.

Here in the United States and the Rocky Mountain West in particular, one narrative epic poem stands out alone from all others: Norman Maclean’s A River Runs Through It, published in 1976 by an old man — a Scot — with a sun-freckled face who, at poem’s end, lets his flies drop in a Montana stream that is, indeed, as cold and as dark as the sky before the long-coming dawn, and so, ultimately, as dark as the story itself. Anyone who has read what Maclean always, privately at least, referred to as his “love poem” to his family, knows that every line in the book scans, that the beauty of the poem’s rhythms and its innuendoes, its highly reflective surfaces and its profound green, blue and black depths, carry the writing far, far beyond the limited boundaries of prose into the very real country of poetry and mystery and awe, so charged with grace and economy is the poem’s language, but after such knowledge, what forgiveness?

Why go and seek to catch a falling star? We know, already, don’t we, who cleft the devil’s foot?

We did.

And the current exemplary and massive effort on the part of Montana’s people to restore health to Maclean’s river proves it.

“There is a fire in water. There is an invisible flame, hidden in water, that creates not heat but life,” writes David Duncan, surely one of Montana’s finest contemporary poets, although, like several others, he remains far better known as a writer of prose. Like other members of Montana’s exotic species, homo sapiens sapiens extraordinalis, Duncan migrated to the state. In other words, he’s a transplant and therefore something of a hybrid and rare avis much like his compadres, Tom McGuane and Rick Bass, Annick Smith, Bill Kittredge and Greg Keeler. Of these writers, however, only McGuane has produced an acknowledged classic on the subject of fly fishing, The Longest Silence, and only McGuane has sustained that silence with anything comparable to the power and beauty we find in Maclean. Taken together, the Scot and the black Irishman McGuane constitute the solid gold standard for the state of the art of poetry, fly fishing and silence — at least in Montana — but probably in all of the English-speaking world, which once included Idaho and Hemingway as well as the other “Lower” 48.

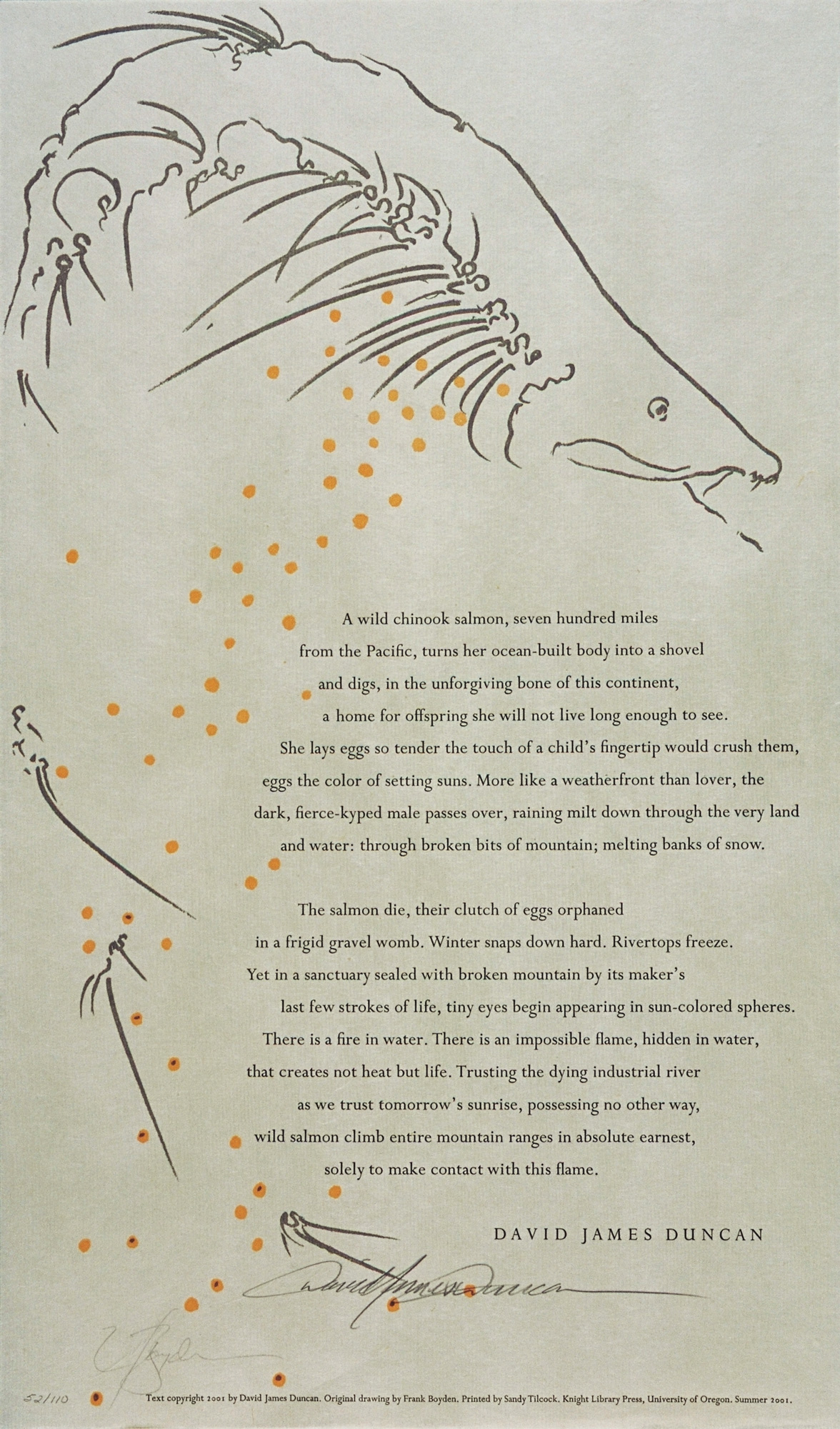

Duncan’s untitled poem, however, printed by Oregon’s Sandy Tilcock on her Lone Goose Press, nevertheless deserves a mention if only because the poem demonstrates in a mere 17 lines the fragility of our estate and the consummate skills of wordsmithing required to express the silence of which Maclean and McGuane dare to speak:

We ought to notice several things about this poem, one of them being that with a little more work this tour de force of language could easily be further sculpted into a shaped poem in the form of two salmon eggs. We should also notice that we can find no fly and no fishing and absolutely no reference to either in this poem David Duncan made from a few scraps of prose taken from his book My Story as Told by Water and then laid out like a series of long, artful casts. We need also to notice that a poem of such power, invested with light and radiance, demanding our every skill as readers as well as every skill the writer can bring to bear down hard on his subject in order to recreate the very life force that animates us all, is, in fact, only a fly, a fake, a forgery, a counterfeit, an artificial bait of falsehood, indeed, a kind of lie meant, and conceived through the intention of its maker, to catch that carp of truth about which Polonius babbles to Reynaldo in Hamlet.

All of which is to say, as the Latin phrase has it, there is more to fishing than catching fish. This much, surely, each fly fisher knows and knows, alas, in a way no mere bait fisher can ever know.

Bait fishing, after all, remains a sport, one practiced by poets (and other idiot savants) as well as perfectly otherwise respectable people who insist on impaling onto their hooks gobs of worms, parts of worms, clusters of foul-smelling cheese and eggs and corn and marshmallows and …

But why go on?

Fly-fishing, like poetry, like silence, is an art, yet even as an art, I want to make only two of many special claims that could be made for it here. Both, I believe, might hold equally true for poetry.

First, the art must be practiced outside by taking the kind of walk Thoreau describes in his famous essay on walking, a walk that requires a physical and mental readiness to adventure into the wild where a bear or a river, through one missed step, might easily (and perhaps even mercifully) end the single and only life each of us is given to live. Anyone who chooses to venture on such a walk as Thoreau envisions had first best have put all of his or her affairs in order. Too few of us have done even that and consequently approach the art unprepared.

Second, the angle of incident is equal to the angle of reflection, and both angles require serious reflection on the part of the angler who wishes to survive the walk. Practiced as an art, fly-fishing is poetry, and the reverse may also prove true as in the case of Duncan’s poem. Practiced as an art, fly-fishing also includes meditation and work as a form of prayer. Practiced as an art, fly-fishing further requires the mastery of certain physical and mental skills as well as a basic literacy concerning the world, requirements formerly (although perhaps no longer) provided at least partly by families and teachers who knew enough to educate children privately at home before sending them off to school.

By the age of 10, Norman Maclean had unintentionally committed himself to becoming a master of the American language as well as a fly fisher. Even earlier, in the late summer of 1910 when the Great Blowup was sending smoke signals from fires burning all over the West to be seen as far away as New England and the nation’s capitol and the street lights of Missoula had to be lit during the day in order for pedestrians to make their way along Higgins Avenue and Front Street, an 8-year-old Norman Maclean had to be forcibly removed by his father, the Reverend Maclean, and other men from an island in the Clark Fork River and escorted to safety all the while protesting the loss of his fly rod back on the island. Members of Reverend Maclean’s congregation believed the apocalypse had arrived and came out to the fish camp to rescue the family.

In the next two years, Maclean’s skills with a pencil and paper, not to mention a fly rod, had advanced to a point where he was allowed to ride his bike to the river alone after his morning-long (and rather grueling) sessions with his father. On his way to the river, or so he told me and others, he made it a habit to ride past (and sometimes around) the building of the nearest grade school where he shouted through the open window while letting go of his handle bars: “How are you doing in there, pals? It’s a great day to be outside, isn’t it? I think I’ll go fishing! See you later, suckers!” And that’s where the truant officers and game wardens teamed up to catch him — fishing. Fly-fishing. So much for the early freedom and education for the young Scot.

As for the miscreant Irishman McGuane, he, too, came from clans of island storytellers and also committed himself very early to the black arts of writing, reading, hunting, and fly fishing while still a boy imagining his life as a rounder and a profligate pretty much as he eventually lived it for a very long time. One of his teachers at Stanford, Wallace Stegner, thought highly enough of McGuane’s unbroken promise as a writer, to send me some of it, and told me stories about him that I only wish I could repeat here. In fact, as we all know, it was McGuane who convinced Redford to undertake the fool’s errand of bringing Maclean’s love poem to his family to the screen by giving Redford a copy of the old man’s book. Thus, together, the four of them brought about the current debacle and impending ruination of our art by the sports, male and female, who can only pretend to practice it and who are now increasing exponentially by numbers the closer one drives to Missoula, Montana. But this, too, may pass as evidenced by the ongoing restoration of the Big Blackfoot River.

If not, what, then, of poetry, of silence and of fly-fishing?

Well, we shall find out.

- Undated photo of man fishing Trick Falls in Glacier National Park. Photo 94.2252, Rollin H. McKay, Archives and Special Collections, Mansfield Library, University of Montana – Missoula

- Text copyright 2001 by David James Duncan | Original artwork by Frank Boyden | designed and printed by Sandy Tilcock at Knight Library Press, University of Oregon in the summer of 2001

- Fisherman with reader in Hammock on the Gallatin River, date unknown. Photo courtesy of Pioneer Museum, Bozeman, Mont.

- Recreational fishing on the Gallatin River, looking downstream toward Castle Rock. Photo courtesy of Pioneer Museum, Bozeman, Mont.

No Comments